BOWLING GREEN, Ohio — A new generation of plastic 10 years in the making is designed to degrade and may someday help reduce plastic pollution.

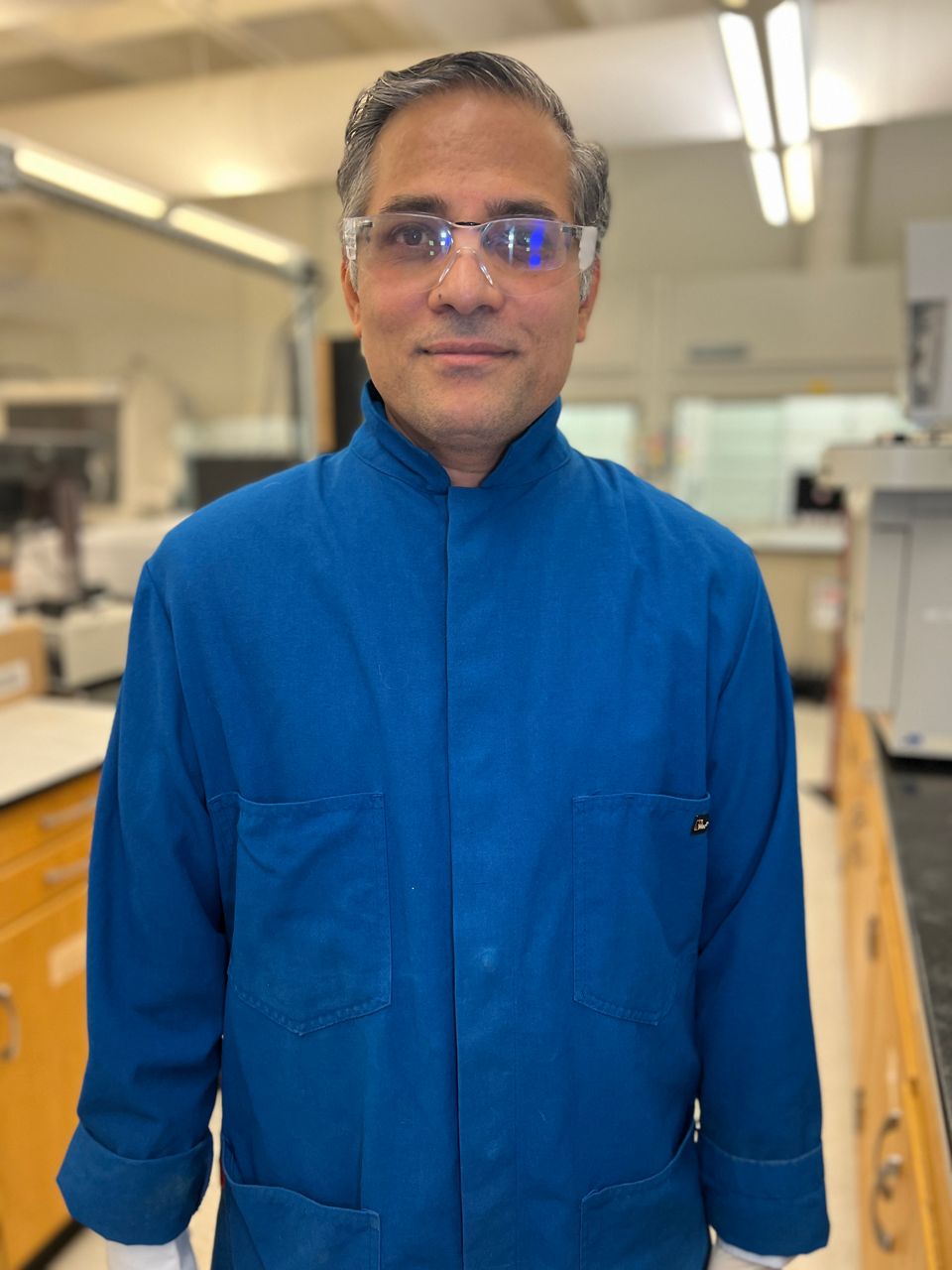

Dr. Jayaraman Sivaguru, a professor in Bowling Green State University's department of chemistry, two professors from North Dakota State University, Dr. Mukund Sibi and Dr. Dean Webster, with their many graduate students, have created a plastic made from vanillin, a chemical found in the extract of a vanilla bean.

“We want to, you know, make the system in such a way that you can recycle it again and again,” Sivaguru said.

The professor also serves as associate director of the University’s internationally recognized Center for Photochemical Sciences.

HOW IT WORKS

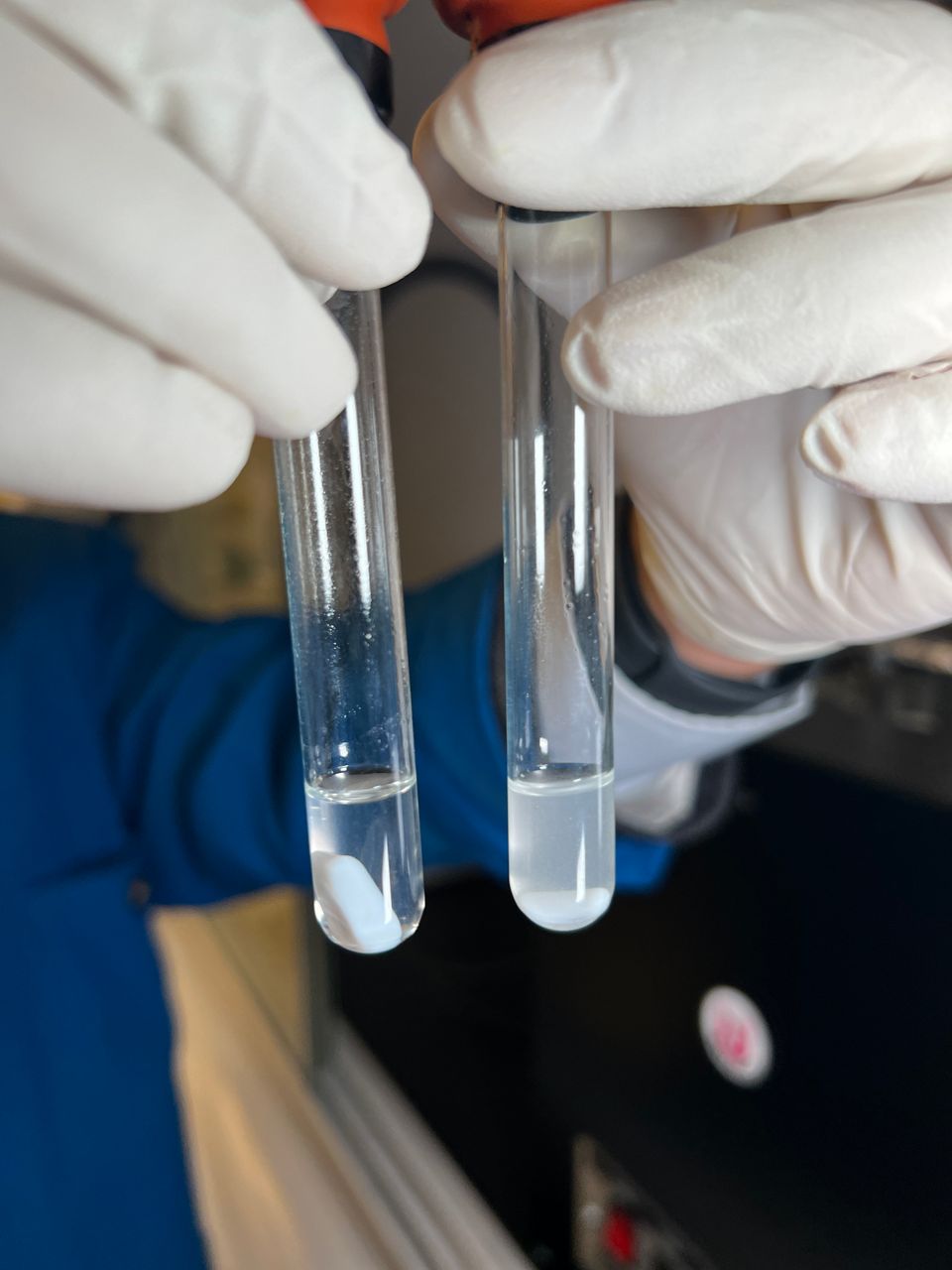

Sivaguru said polymers can be natural or synthetic and are created when small molecules, also known as monomers, combine chemically to form a larger network of connected molecules. Plastic is a specific type of polymer composed of a long chain of polymers. The polymer Sivaguru and his team developed is made from vanillin, a biomass material that is renewable.

To simulate the recycling process, the first step is to disperse the plant-derived polymer in a solvent, remove the oxygen that is dissolved in the solvent and then put it under 300 nanometers, an ultraviolet light wavelength that’s invisible to the human eye, so the polymer breaks down and can be used again to build more plastic. For non-science people, he compares it to legos.

“You can consider this entire process as making a Lego piece that is coming from plants,” Sivaguru said. “So, and eventually that Lego piece is being assembled into a Lego set. So, that is your polymer. And then, when the lifetime of the polymer is lower, you shine light on the Lego set, essentially breaks down and goes back to the Lego piece you started with, so, that you can not only degrade it, you can recycle it.”

Conventional single-use plastic is often manufactured from fossil fuels and is designed to last forever, yet is often only used for a few minutes before being thrown away. It eventually breaks down into microplastics, some so small the eye can’t see. Microplastics have been found in our food, our drinking water, on our lands and in our oceans, and studies show they are affecting our environment and our health.

“All plastic degrades, you know, the question is, you know, when it degrades, what happens to it. So, some of the plastics go as microplastics, some of them can be you know, made to recycle, you know, if you can, you know, capture it using the recycling bin that we typically put our plastic in and you can remake it to a different form,” Sivaguru said. “Our approach is, you know, how can we make plastic not only degradable and recyclable but also having a sustainable source, you know, which is biomass. So, we want to address all three issues, you know, it's a biomass derived, recyclable and degradable materials.”

The idea is to develop a more sustainable and safer form of plastic that is still durable, to use in everyday products.

“What we have done essentially is instead of allowing it to degrade over time, you switch on, you know, essentially switch on the light by pressing a button," Sivaguru said. "Now, it is degraded, under your control, so it is programmed to degrade. So that way, you don't end up with this microplastic issue. It just goes back to the material you started with so that you can again do the recycling of the same plastic.”

Critics of plastic recycling said it’s a distraction from real solutions like producing and using less plastic.

“There's always like some new announcements, that's gonna fix the plastic problem that is not actually just making less plastic, but that distracts the public, that distracts legislators, and it's our job to bring attention back to policies that would reduce plastic production in the first place,” said Alexis Goldsmith, organizing director of Beyond Plastics, a nonprofit dedicated to ending the use of single-use plastics.

Organizations like Beyond Plastics said it’s very hard to waste-manage plastic and capture it before it leaks into the environment, making plastic, even bioplastic, not better for the environment if you need a lab to degrade it. While bioplastics are an improvement compared to traditional plastics, Beyond Plastics said they’re trying to get people to focus on immediate calls-to-action like banning single-use plastics like plastic bags and unnecessary plastic packaging.

“If your bathroom was flooding, if your bathtub was overflowing, you wouldn't start bailing it out with a teaspoon, you would turn off the tap first,” Goldsmith said. “And that's what we need to do.”

Sivaguru said getting rid of plastics all together would be a huge undertaking, instead, he said we have to find ways to adapt.

This research is more than 10 years in the making, and is now patent-protected, but still has years of research to go. Sivaguru said the research would be nothing without the many graduate students he instructs.

“It's basically making the world a better place,” said Sruthy Baburaj, a PhD student in the Center for Photochemical Sciences at BGSU. “I’m really honored to be a part of this group and to find the solution for a problem that has been in the environment or in this universe for a really long time.”

The system is currently 65% recyclable, but he said there are still years of research to be done. Sivaguru said the end goal is to get the system to about 95% recyclability, commercialize it and put it to practical use.

He calls it a promising approach but knows it can’t be the only approach. To solve a global problem of this magnitude, he said we need multiple creations and solutions.

“There are other processes that I know people are evaluating and you know, like I said, you know, a problem like this has to be tackled with a multi-pronged approach," he said. "You know, it is not that, you know, only light will solve this issue, no, that's not how this is going to work. It is going to be a multi-pronged issue that needs multiple different solutions coming from different angles.”

The researchers' findings were published in Angewandte Chemie, one of the world’s premier chemistry journals.