CINCINNATI — After months of calling around, filling out applications, and even showing up at the office in person, Umekia Bruton is tired of waiting.

Since losing her job, Bruton fell behind on rent and energy bills, and at the end of the month, she plans to move out of the apartment she can no longer afford.

Things aren’t much better for Kimberly, who declined to share her last name. She’s been trying to catch up on rent since last fall and was lucky enough to secure approval for emergency rental assistance. Yet months later, it has yet to arrive.

Now she said her landlord is threatening to evict her if she can’t provide anything more than a promise to pay.

Stories like these are all too familiar to groups like the Cincinnati-Hamilton Community Action Agency, which is tasked with distributing the county’s allocation of federal Emergency Rental Assistance to those in need.

A pandemic relief program meant to prevent evictions, the treasury distributed millions of dollars to the states to allocate to renters in need until the end of Sept. 2022. Some agencies, including CAA, got a three-month extension to distribute recently reallocated funds.

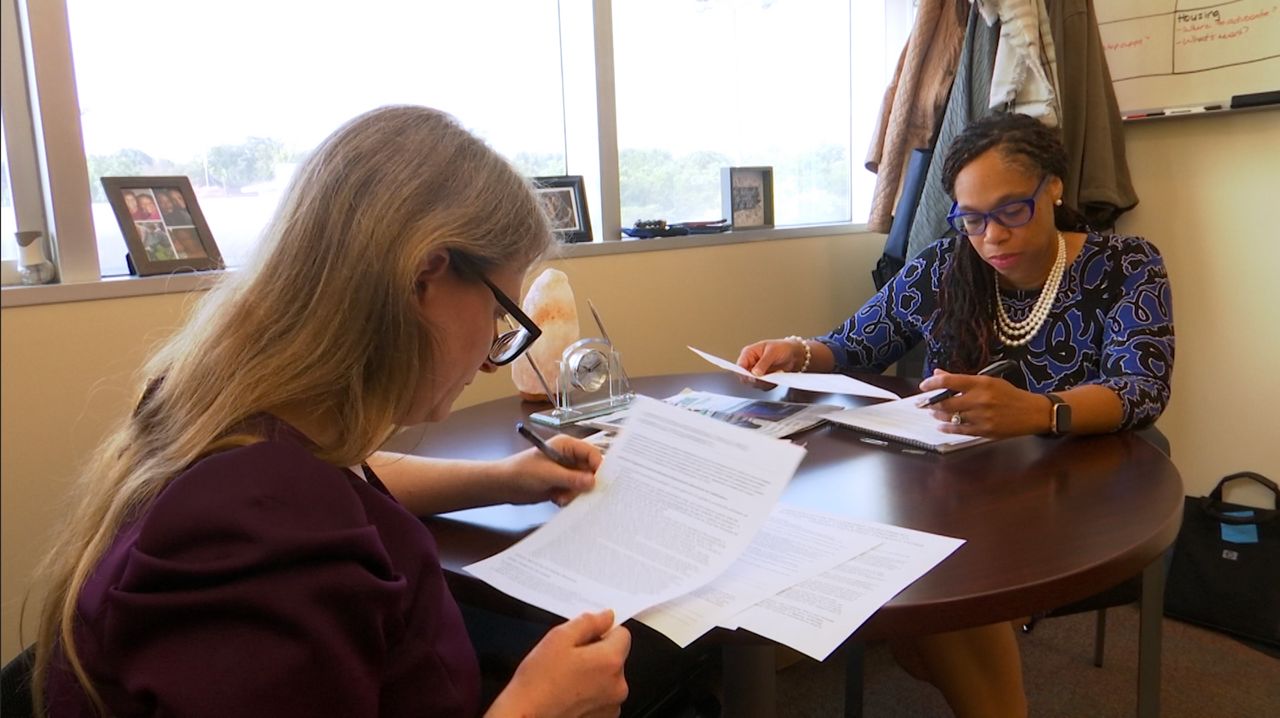

Since the ERA program began in Feb. 2021, CAA has distributed more than $30 million to more than 7,000 households to help them stay in their homes, yet according to Ebony Griggs-Griffin, the vice president of community services, the need remains as high as ever.

“I believe that people think that the pandemic or the impact of the pandemic has ended, and it has not,” Griggs-Griffin said.

Meanwhile, with thousands of applications in their pipeline and a looming deadline to allocate those funds by the end of the year, CAA suspended new applications at the end of end of August hoping to catch up.

Households still recovering from job loss, a death in the family or a cut to hours to cope with a lack of child care through the pandemic have been among the hardest hit as inflation peaked, making their food, commute and housing far more expensive. The agency said clients have reported their rents increasing by hundreds of dollars a month, making it nearly impossible to keep up with the payments.

“Families are making a choice between whether or not they pay their rent, they pay their utilities or whether or not they get food for that week,” Griggs-Griffin said.

The problem isn’t unique to Hamilton County or even Ohio. Community Action Agencies across the state are reporting they’re running low on funds and several states, including California, New York, and Texas, ran out of ERA funds as early as Jan. 2022.

Ohio, however, has been slow to allocate the roughly half a billion dollars it received in the first round of ERA with the National Low Income Housing Coalition reporting as of Sept. 13, 59% of its funds have been paid to households.

Any funds not obligated as of Dec. 29, 2022, must be returned to the federal government, potentially leaving millions in rental assistance on the table, while thousands across the state face eviction.

Meanwhile, groups like CAA say they’re running out of funds. The agency was allocated $42 million in rental assistance funding in 2021, but after processing thousands of applications through the past year and a half, the agency is running short.

At the time the agency passed new applications at the end of August, project coordinator Jaclyn Saylor said there were roughly 6,000 active applications for CAA to manage over the next three months.

“We need funds and we need more staff,” she said. “It is something like $15 million we would need to be able to service everyone that we currently have an application for and that’s not what we currently have.”

CAA hopes to receive an additional $9.1 million from Ohio’s ERA 2 allocation, but the state has not confirmed those funds. If approved, Ohio agencies have until 2025 to distribute the aid. Saylor doubts it would last much longer than next year.

“There are a lot of people that we’re not able to help at this time and it’s very tragic,” she said. “We don’t have the luxury of time.”

As CAA works through its backlog of applications, Griggs-Griffin said the agency has been prioritizing those clients who are urgently facing eviction and may appear in court this week or next.

In Cincinnati, through the city’s “Pay to Stay” policy, if tenants can get a voucher from CAA proving the funds for back rent are on their way, it can serve as a defense against eviction. Though that voucher needs to come before proceedings wrap up and Saylor said that’s getting harder to manage as more and more cases head to court. Weekly eviction filings have been on the rise since April.

“Landlords are taking tenants to eviction court sooner,” she said. “35% of our applications at time of application already have that court date or an eviction notice.”

If clients are outside the city limits or can’t find the legal representation to argue “Pay to Stay,” Saylor said, finding the funds is even more urgent as the landlord is free to follow through on the eviction.

In the meantime, clients are losing hope.

Bruton plans to move, considering herself lucky she doesn’t have children and will start a new job in October. She fears she’ll have to move out of the county or out of the state to find anything affordable.

“I just pray that this gets better for me and for everybody else, but this is sad,” she said.

Another client, Tiffany, who also declined to share her last name, fell behind on rent when she was laid off. Her first court appearance was in early September. Her landlord told her she has 30 days to come up with a payment. She’s been waiting for CAA’s approval since June and now fears she’ll have to take her five-year-old to a shelter.

“I can’t sleep at night because of this,” she said.

Unless something changes, Saylor believes this is just the beginning of an eviction crisis in the Cincinnati area. With a pause on new applications and funding set to run out at the end of the year, she’s worried there will be thousands more cases that won’t get the option to ask for help.

“This is just a band-aid, this’ll help someone in this situation for a moment, but when they can’t say their rent again, it will come up again,” she said. “We’re going to be seeing a bigger homeless problem than we are now.”

Meanwhile, clients like Bruton are doubtful there’s enough help to go around even now.

“It’s 6,000 people lost in the system,” Bruton said. “Who are you gonna pick and choose to help? Because you’re not going to be able to help all 6,000 of people.”