CINCINNATI — On a busy night at one of his three restaurants, Jose Salazar stands at the pass, checking every tiny detail on the dishes coming his way. Each drizzle of olive oil, every sprinkle of salt has a place on the plate because Salazar said consistency keeps him in business.

That attention to detail takes concentration, dedication and, most of all, energy. According to Salazar, he couldn’t keep it up if he was still drinking.

Salazar has been on the Cincinnati restaurant scene for 13 years. Starting out at the Cincinnatian Hotel, he left to open his first restaurant Salazar in 2013. Then two years later he opened Mita downtown and not long after, he eyed another project, a restaurant just across the street from Findlay Market.

“I knew I would be doing 80- to 100-hour weeks to get things up and running,” he said.

That’s when Salazar decided something had to give.

“I convinced myself that I didn’t need to be sober but that this would help me,” he said.

At first, Salazar said he didn’t believe he had a problem. Drinking is a big part of the culinary industry, both as a part of service and a way to decompress afterward.

“It was not uncommon to go out four, five nights a week after work,” he said.

When Salazar decided to take a short break from alcohol in 2019 though, he said the experience revealed something deeper.

“I probably should have quit entirely, long before,” he said.

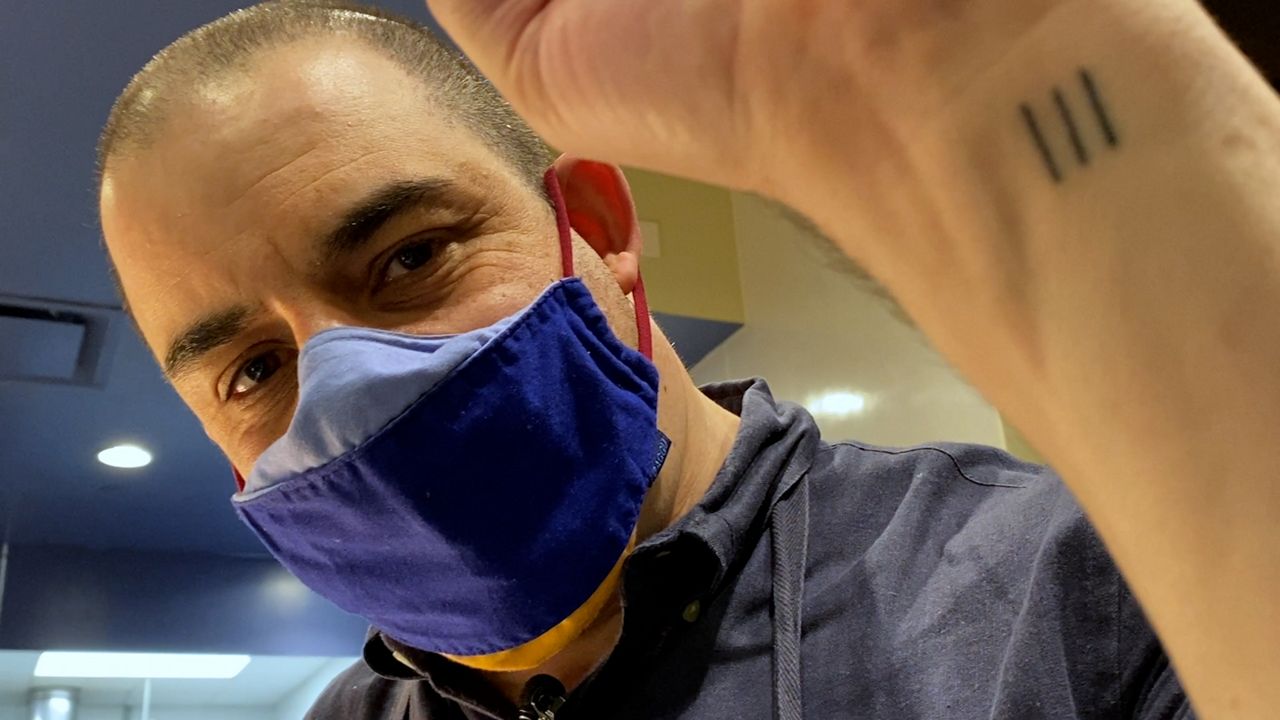

Three years later, he hasn’t looked back.

According to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics, of the millions of American adults who choose to consume alcohol, 6.7% will develop alcohol use disorder, and every year, 95,000 die from the effects of the drug.

Salazar believes his troubles started when he began to rely on drinking to calm his anxiety.

“Alcohol, in retrospect, only made it worse,” he said. “ It only kind of boosted that anxiety, only made me more edgy, only made me more erratic and grumpy.”

Ashley Cook, who founded the Cincinnati Sober Fun group on Facebook, said they too noticed they were relying too heavily on drinking to self-medicate.

“I was like I need to take a break from this my body is not handling this anymore,” Cook said. “I was like a daily binge drinker, and I didn’t see that as alcoholism at the time, but once I stopped drinking and said I’m going to take a break, I actually liked how I felt and I just stayed with it.”

Now six and a half years sober, Cook said quitting gave them a clearer picture of what was causing that stress and how to find a healthier way to manage it.

"For me it was like, my family stresses me out all of the retail stress of my job stresses me out,” they said.

For Salazar, exercise filled the void and he said while he still gets cravings for a drink every now and then, he focuses on habits that give him energy, rather than take it away.

“Especially in this kind of chaotic, fast-paced industry that I’m in,” he said.

Salazar and Cook both said breaking the news to their friends turned out to be an unexpected challenge of sobriety.

“If you tell somebody that you’re quitting smoking, they clap for you, they congratulate you and they don’t question it in any way,” he said. “But when it comes to alcohol, it’s immediately the first question is why.”

Cook said many of their friends considered sobriety a phase and would continue inviting Cook to bars or alcohol-centric parties.

“It’s really hard to create that boundary with people and carve out that little slice of the world that you need without alcohol,” they said.

Even outside of social groups, Cook said sober Cincinnatians live in a city that relies on a culture that assumes everyone drinks.

“I feel like a lot of people have issues finding things to do that don’t involve alcohol, you go to a concert there’s a bar there you go to Riverbend there’s a lawn there where everyone is drinking, there’s bars on the lawn there,” they said. “it’s hard to get away from it and it was hard for me to find things to do that weren’t at bars.”

That’s the reason Cook wanted to start a sober group, to share events around the city and plan get-togethers that don’t involve drinking.

For Salazar though, confronting alcohol every day is an unavoidable part of the job. All of his restaurants have bars, and he’s not considering shutting them down.

“I love curating a menu that is paired with alcohol that is symbiotic,” he said.

He said the relationship between wine and food is a big part of the culinary experience and he understands people go to restaurants to try new drinks or cocktails.

“I think they really compliment each other tremendously, and so having food without alcohol would be weird but it’s not necessary,” Salazar said.

That’s why Salazar said he’s made a point to design menus that don’t leave out sober guests. All of his restaurants offer mocktail options, and he’s partnered with Deeper Roots Coffee to get nitro taps installed at all his restaurants.

“It’s something I’m planning to expand,” he said.

Salazar considers himself fortunate that he’s not triggered working so close to a fully stocked bar every day, but he said when the cravings do come, he focuses on how much better he feels after closing that chapter of his life and remembers he’s far from alone.

“A lot of the people who helped me get sober are actually in the industry and I just want to let people know that it’s possible,” he said.

Now, celebrating three years sober and running off the momentum of his newfound energy, Salazar said he’s ready to start another new chapter, a fourth eatery. In 2022, he plans to put together a bodega-style deli in the Columbia-Tusculum neighborhood.

“I mean that’s why I don’t drink, because if I was drinking, I wouldn’t have the energy, I would be sleeping all day,” he said.