COLUMBUS, Ohio (AP) — The announcement that the federal government will review the Columbus police department and provide technical assistance in areas such as training and recruitment is a far cry from the last time the Justice Department examined the agency and signals the city’s willingness to cooperate, analysts say.

The review announced last week will be conducted by the Justice Department’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services and follows a series of fatal police shootings of Black people and the city’s heavily criticized response to last year’s racial injustice protests.

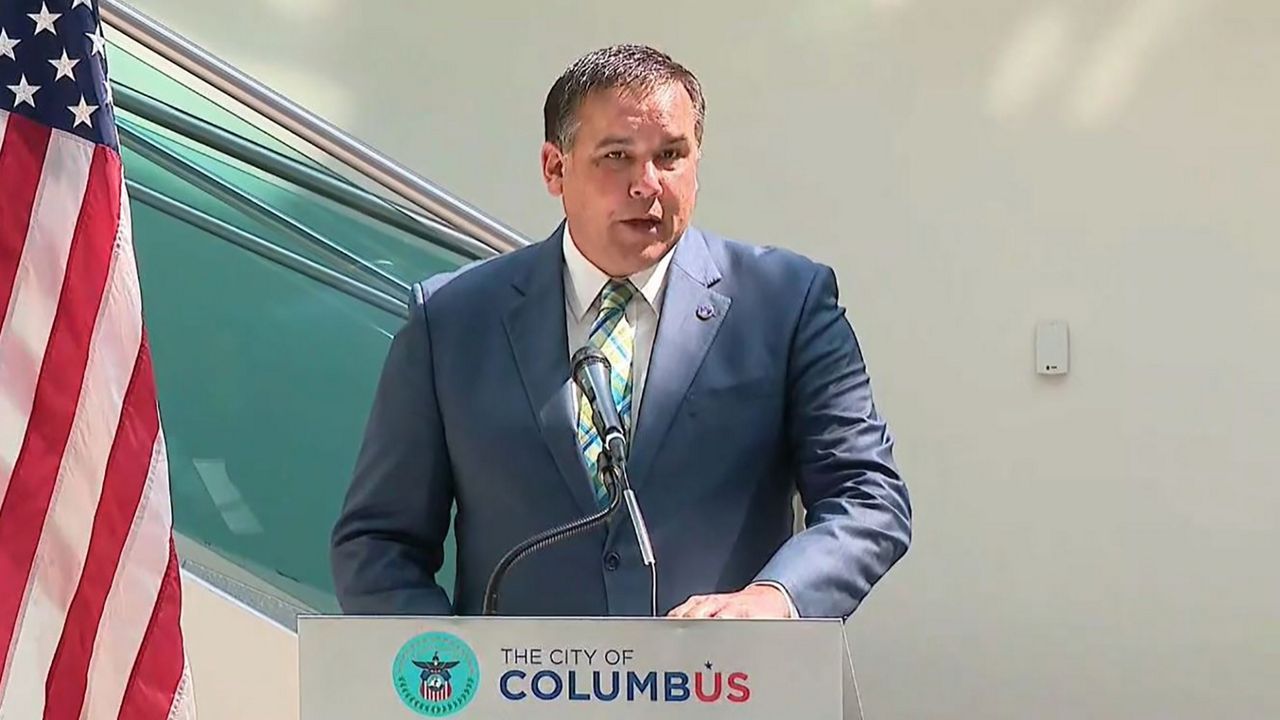

The review stems from an invitation by Columbus Mayor Andrew Ginther and City Attorney Zach Klein, both Democrats who have pushed for changes to the police department, putting them at times at odds with both rank-and-file officers and police brass.

By contrast, the Justice Department sued the city in 1999, accusing officers of routinely violating people’s civil rights through illegal searches, false arrests and excessive force. The city fought the lawsuit and the government ultimately bowed out.

WHY DID THE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT INTERVENE?

The government accepted an April invitation to conduct a review that came after a white officer fatally shot 16-year-old Ma’Khia Bryant while the teenager, who was Black, was swinging a knife at a woman. But that killing was more like the final straw than a precipitating event.

The same month, a federal judge ripped the city for officers’ handling of racial injustice protests in May and June of 2020 following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, saying police ran “amok.”

Meanwhile, white Columbus officers were involved in several other fatal shootings of Black people in the preceding months and years, among them the Dec. 22 killing of 47-year-old Andre Hill as he walked out of a garage holding a cell phone, and the 2016 fatal shooting of 13-year-old Tyre King during a robbery investigation.

Records show that Black residents, about 28% of the Columbus population, accounted for about half of all uses of police force from 2015 through 2019.

Ginther has already implemented changes to the police department, from body worn cameras for officers to spearheading the city’s first-ever civilian police review board. But when the mayor requested the federal review, he said Columbus needed help because of “fierce opposition” to reform within the agency.

WHAT TYPE OF REVIEW IS THIS?

The review will be conducted by the Justice Department’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services and will consist of what the department is calling technical assistance in areas such as training, recruitment including a focus on diversity, technology, and creating an early intervention system for officers.

The COPS office, established in 1994, embraces the concept of community policing, which as the name implies involves police departments strengthening relationships with residents and advocacy groups and helping improve the training that officers undergo.

Importantly, the COPS office also provides money to agencies, and has awarded more than $14 billion in grants to more than 13,000 state, local and tribal law enforcement agencies to pay for the the hiring and redeployment of more than 134,000 officers.

That makes it an attractive option for Columbus, since the government could have announced a “pattern and practices investigation” conducted by the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. Such an approach typically assumes a combative relationship that starts in the courts and can include a federal judge’s oversight of an agency for years. It can also require expensive changes to departmental policy shouldered by the city.

WHAT DOES THIS REVIEW MEAN FOR COLUMBUS?

The COPS review suggests a more collaborative process, said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a nonprofit Washington-based police think tank.

The city is inviting federal oversight and asking for assistance of a technical variety, similar to requests made by Las Vegas and Philadelphia during the administration of President Barack Obama. Doing so will allow Columbus itself to take the lead on making changes once it receives the federal feedback, Wexler said.

“It’s significant whenever a city steps up and says we need help,” he said. “That says to me that Columbus wants to change the way they do business.”

In 1999, the Justice Department sued the city, accusing officers of routinely violating people’s civil rights through illegal searches, false arrests and excessive force. A year later, the government added a racial profiling complaint, alleging that from 1994 to 1999, Black people in Columbus were almost three times as likely as white people to be the subject of traffic stops in which one or more tickets were issued.

A federal judge in 2002 dismissed the lawsuit after the city, which had fought it, made changes on the use of police force and handling of complaints against officers.

Columbus may understand it might not be so lucky the second time around, said Zachary Powell, a criminal justice professor at California State University-San Bernardino.

The administration of former President Donald Trump, a Republican, indicated it was reluctant to use federal consent decrees to enforce change in departments. President Joe Biden, a Democrat, has signaled the opposite, Powell said. Powell cited Justice probes announced this year of excessive force allegations against Phoenix police and of policing practices in Minneapolis following Floyd’s killing.

If Columbus can “show that they’re being cooperative, they’re being proactive, they’re maybe hoping they can get funding to support some of the changes that they need to,” Powell said. “And also to have a more cooperative relationship with the Department of Justice, if the Department of Justice decides that they need enforcement action.”

Columbus spokesperson Melanie Crabill said the city has no expectation of funding. “We’re just happy to be working together and ready to get started,” she said.