WASHINGTON, D.C. — Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives desperately want to retake the majority, and they only need to win back five seats from Democrats to do it.

What You Need To Know

- Ohio will lose one of its 16 congressional districts next year

- State legislatures are beginning to draw the districts under new, complicated rules

- Experts say Ohio’s map will likely remain quite partisan in favor of Republicans

- Control of the U.S. House could end up being decided by Ohio

How Ohio’s congressional map is redrawn could decide whether they will be successful.

State lawmakers have begun the politically-charged process of drawing new district boundaries based on data from the 2020 census.

“There are a lot of moving pieces in Ohio. And there are a lot of possible outcomes, I think,” said Kyle Kondik, an Ohio native who analyzes elections for the University of Virginia.

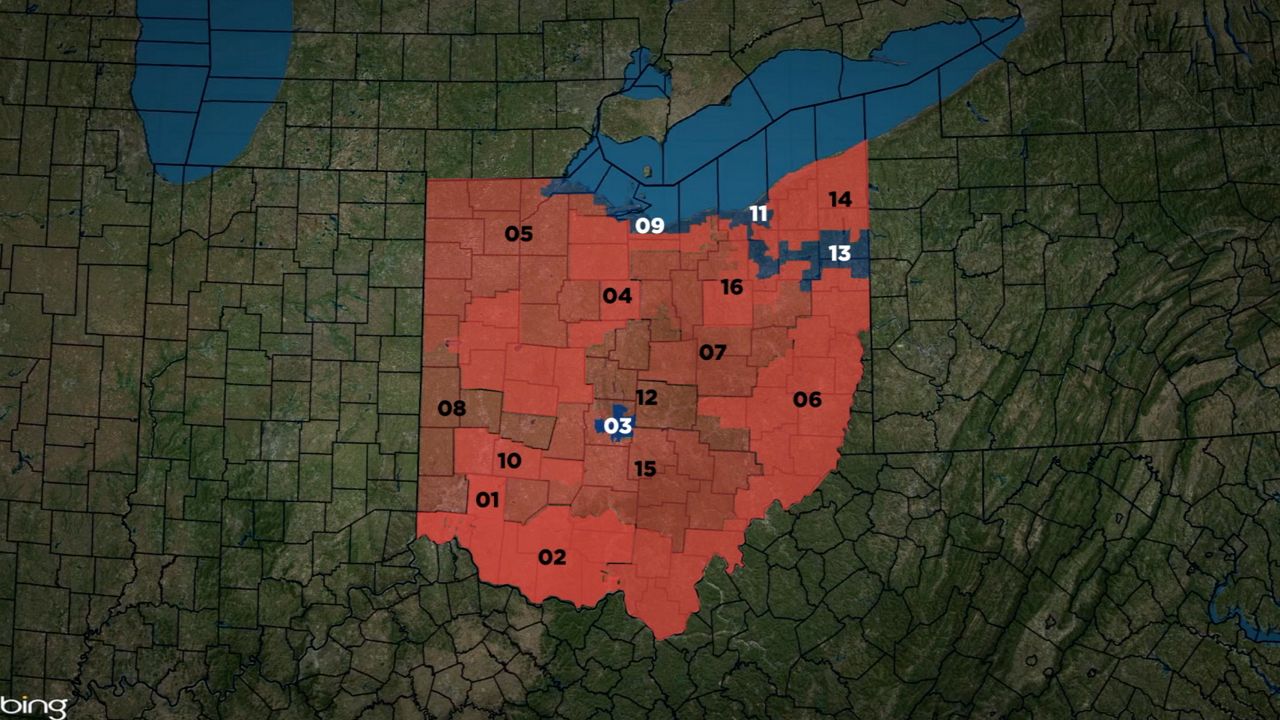

Ohio has had 16 congressional districts for the last decade.

The lines were drawn by Republican state lawmakers to create 12 Republican-leaning and four Democratic-leaning districts; and the gerrymandering worked because no seat has flipped to the other party in the last 10 years.

“Ohio has not had much competition in congressional elections in recent years,” Kondik told Spectrum News. “Wouldn't it be great if you actually had seats that could actually swing from one election to the next? And were actually responsive to public opinion?”

In 2018, Ohio voters approved sweeping redistricting reforms with the goal of reducing gerrymandering and creating more competitive elections. The new rules are being applied for the first time this year.

But Republicans enjoy a commanding advantage in the statehouse, which will likely give the party the upper hand in drawing new district lines.

Ohio will lose one seat in Congress because other states grew faster, so it puts the current 16 House members in an awkward position of having to watch from the sidelines as their future districts get drawn and one of them gets pushed out.

Cincinnati Republican Steve Chabot and Toledo Democrat Marcy Kaptur could see their districts redrawn in a way that makes their reelection chances harder. And Mahoning Valley Democrat Tim Ryan’s district could face the same fate, though he’s running for U.S. Senate.

“I hope it’s a good district, but I’ll do the best I can, whatever it looks like,” Chabot recently told Spectrum News.

Chabot represents southern Ohio’s 1st District, but the new reforms say Cincinnati can’t be split into two districts like it currently is. So Chabot could end up running in an increasingly blue Hamilton County without red Warren County balancing him out.

Kaptur (D, OH-9) represents a sliver of the state from Toledo to Cleveland that’s often referred to as the “snake on the lake.” Her district has long been at risk of being absorbed by a neighboring Republican one.

In Northeast Ohio, Ryan’s 13th District has swung almost 30 points to Republicans in recent years. It theoretically could be absorbed by the GOP districts next door because Ryan won’t be running for reelection as he pursues a Senate bid.

“It’s supposed to be a little more fair, but there’s no evidence that it will be,” Ryan told Spectrum News. “I think it’ll be, you know, the Republicans are going to draw the lines and they’re going to draw them to their favor. And I think that’s what contributes to the partisanship down here.”

Katy Rossiter, Ph.D., a geographer who worked for the Census Bureau and now teaches at Ohio Northern University, said there’s long been a debate over what makes a congressional district fair.

“Do we want competitive districts and they're half urban and half rural? You know, half red, half blue, and the best person wins?” Rossiter said. “Or do you want to group together like voters, so they all get to pick that one person that represents them, and they all sort of feel good about that decision?”

But John Curiel, Ph.D., a political scientist who also teaches at Ohio Northern, said the politicians who oversee redistricting usually find the temptations of gerrymandering irresistible.

“If you draw a good map, there's essentially no need to campaign so long as people stay loyal partisans, which there is no evidence to say they wouldn't for the foreseeable future,” Curiel said.

The new redistricting process in Ohio is believed to be one of the most complicated in the nation.

Designed to reduce the likelihood of partisan gerrymandering, the rules limit the number of counties that can be divided, roughly two dozen of the state’s 88 counties, and encourage Republicans and Democrats to compromise by setting thresholds for bipartisan support state lawmakers have to try to meet while voting.

The new mapmaking process could be carried out in as quickly as one stage, or as long as four stages, depending on how well state lawmakers can work together.

In the first stage, lawmakers have until Sept. 30 to vote on a proposed map. If 60% of state representatives and senators vote in favor, including half of all Democrats, the maps will go into effect for 10 years.

If that doesn’t happen, then stage two begins. A seven-member redistricting commission takes over. The commission is made up of five Republicans, including Gov. Mike DeWine, and two Democrats. If four of the seven members, including both Democrats, vote in favor by Oct. 31, then the maps go into effect for 10 years.

If the commission fails, then the process returns to the statehouse and lawmakers will try again to pass 10-year maps with 60% approval by Nov. 30, but only one-third of Democrats would have to sign on this time.

If that doesn’t work, then Republican state lawmakers, who hold a supermajority, will be allowed to draw up their preferred maps and pass them, but they would only go into effect for four years.

And throughout each stage, there’s the potential for legal challenges that can slow things down even more.

While the reforms could produce more competitive seats, experts said because Ohio has gotten more Republican, the maps will likely remain partisan and leave redistricting reform advocates frustrated.

“I hope that in a state that votes both for Donald Trump as well as Barack Obama, right? A state like that should be 50/50,” Rep. Kaptur told Spectrum News.