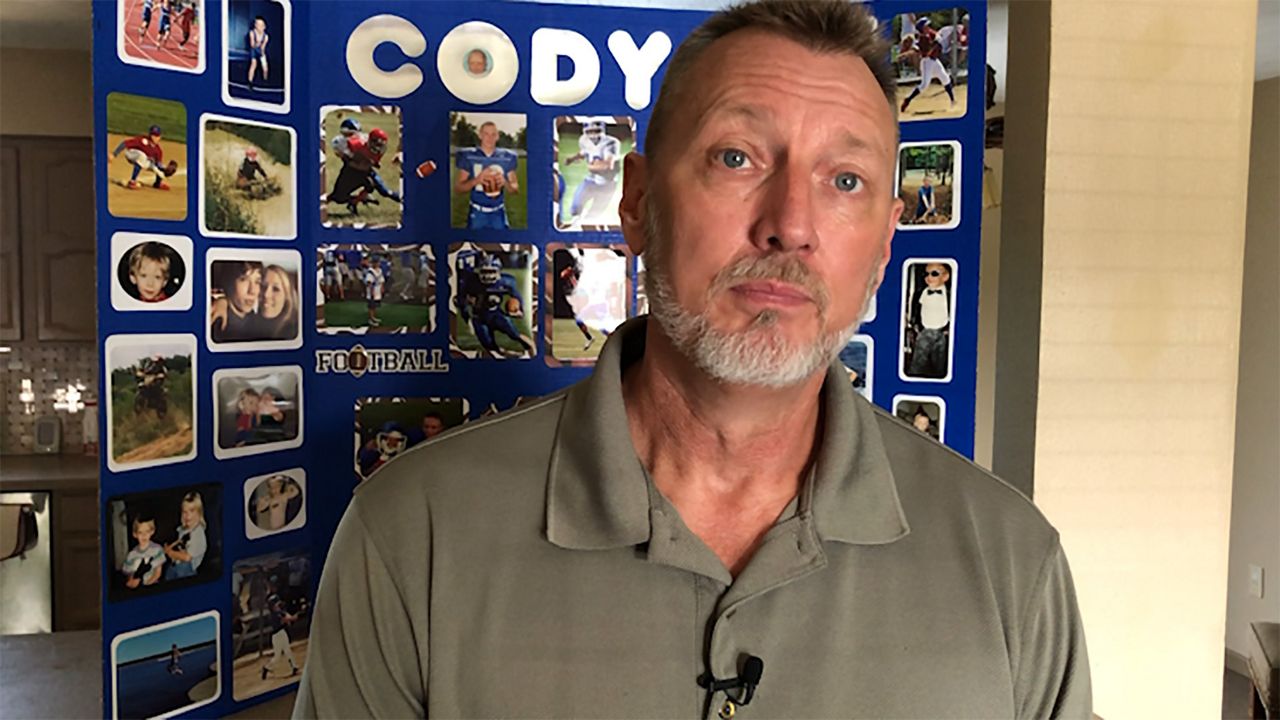

MIAMISBURG, Ohio — A blue-number yard marker 13 sits in front of Darren Hamblin’s house — it’s a reminder of his son Cody.

“I think about a lot of the good times we had, then it always circles back to the bad times,” Hamblin said. “One thing I never think about is watching them play. I definitely don’t want to watch (high school) football anymore.”

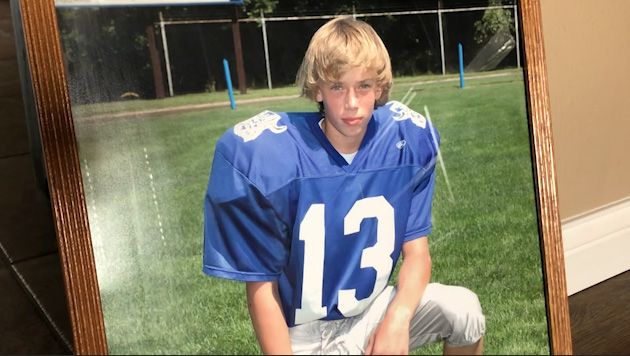

Cody played for the Miamisburg Vikings football team.

“He was the quarterback, the starting quarterback,” he said. “But he was a running quarterback. So yeah, he pretty much had his hand on the ball on every play.”

Cody died suddenly in 2016 at the age of 22. He had a seizure while fishing with his grandfather, fell into a lake and drowned.

After Cody’s death, Hamblin said he searched his mind for answers. Which led him to think about his football career. He recalled a game in 2009 — the first time he knew his son sustained a concussion.

“The trainer came up and yelled for us to come down to the fence,” Hamblin said. “He said, ‘Cody’s got a concussion. We’re taking him in to the locker room and he won’t be back out to play the rest of the game.’ This was in the first quarter.”

But right after halftime, Cody returned to the field.

“Here comes Cody, marching out on the field, starting running back. We looked at each other like, what the heck is going on? Same trainer comes up and he said, ‘Hey, the doctor cleared him. He said that it was just mild. He’s okay to play.’”

The Ohio High School Athletic Association (OHSAA) has since put rules in place to make athletes sit out after being diagnosed with concussion symptoms.

Those rules were not in place when Cody played. He went on to have a great game. But years later, he revealed something concerning.

“He never remembered that game for the rest of his life,” Hamblin said. “He didn’t remember before the impact or after. I found that pretty amazing.”

After Cody’s death, Hamblin had his son’s brain analyzed by North Shore Neurological Institute in Chicago to determine if Cody had Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in people with a history of repetitive brain trauma.

“When he contacted me back, he said, yeah, we found three distinct areas of brain damage,” Hamblin said. "He said textbook-wise, they might say CTE level one. He’s like, 'Me looking at this, I might say CTE level 2 from my experience.' It’s like wow, this kid only played through high school.”

Darren said Cody played football from age 7 until the end of his senior year of high school. And while he cannot say how many concussions his son suffered, he feels strongly that repeated head trauma ultimately contributed to his son’s death.

“I don’t blame anybody or an organization, football organization for anything,” Hamblin said. “I mean, I think they only did what they thought they were supposed to do. And I don’t think CTE or brain damage when you’re playing football is just caused by concussions. I truly believe it just repeated trauma. Just the hitting over and over.”

It’s been eight years since Cody last took the field for Miamisburg High School, and many protocols have since changed with concussions being thrust into the forefront of player safety discussions.

The OHSAA has a medical advisory board that’s in charge of establishing safety and monitoring guidelines. One of the most important guidelines is making sure student-athletes are not subjected to returning to action after showing signs of a concussion.

Kettering Health Network Athletic Trainer Jeff Von De Linde said preventing second impact syndrome is the highest priority.

“If they sustained a blow to the head their neck their body which causes any kind of symptomatic changes to arise, they really need to just sit out and stop participating,” Von De Linde said. “The concern would be that if you were having those symptoms and you continue to play and you get hit again that you could then develop second impact syndrome, which could be catastrophic or fatal. Even though it’s rare for that to happen there are reported incidences and that’s what we’re trying to protect from.”

The OHSAA said 69 concussions were reported in football in 2018 and 2019 — but that number may be low.

A spokesman from the OHSAA said concussion data is only collected from contests when officials pause a game to remove a player who is showing symptoms.

Hamblin is concerned with this practice as it only displays a portion of the entire picture.

“There’s at least the same amount of hitting, I would actually say a lot more hitting, and just as hard in practices these kids are doing,” Hamblin said. “And when they’re in team practices there’s no doctor on the sideline.”

Hamblin is now an advocate for player safety. His son’s story is a part of the book ‘Brain Damaged’ and has a pending lawsuit against helmet company Riddell.

Hamblin is hopeful better monitoring techniques can be implemented across the state. And offers this advice to parents.

“My advice would be, number one, would be (play) flag football, as long as you can. Cause you get to run, you get to throw, you get to catch, you get to score touchdowns. Everything you can do in a regular game, except you’re not getting your head beat in, over and over. I would say stay away from tackle until you’re an adult.”

OHSAA Football Administrator Beau Rugg said concussions are being handled better all across the state of Ohio compared to 10 years ago. And as each year passes, more improvements continue to be made.