FAIRFIELD, Ohio — Leaning over a small table alongside her 6-year-old daughter, Amy Parker spends her afternoons checking spelling words and arithmetic, dinner in the oven and dishes in the sink.

“I’m a normal lady,” she said with a laugh, describing her life today.

Yet, Parker revels that while she was in active addiction, a life like this seemed impossible.

“Fifteen years ago, I was waiting to die,” she said. “I was completely unhappy and depressed and lived a horrible, horrible life.”

In the grips of the disease of addiction, Parker said opioids were a dominating force in her life since she was a teenager.

At 14, she had the first of what would become a series of seven knee surgeries.

“I had three on the right knee and four on the left knee all between the ages of 14 and 19,” she said. “And with every single surgery was 15 prescriptions of Vicodin.”

From that point on, Parker said spent most of her time looking for a way to mask the pain that wouldn’t seem to go away.

“I could always go to an emergency room and say I fell or whatever and walk out with a prescription of pain pills every time,” she said.

Then in 2009, Parker said the doctors began to see a pattern and turned her away, but not before one nurse slipped her the number to a pain clinic.

“It wasn’t a legitimate pain clinic. It was a pill mill in Hamilton, Ohio,” she said. “I walked out of that office with a prescription for 120 Opana, 120 Percocet, morphine pills like crazy. I never had that much before.”

Then, when she ran out of those pills, Parker turned to heroin.

“It’s like I signed away my soul right then,” she said. “I had no other choice it felt like.”

Parker said she turned to lying, cheating, stealing and dealing, whatever it took to end the day high.

“There’s been times where I had woken up and the needle was still in my arm and I’m alone and I’m looking around like, ‘Ooh, that was a close one, where’s my drugs? I need to do it again,’” she said.

At the same time, she was trapped by her addiction, Parker said she felt trapped in an abusive relationship. It wasn’t until she found herself on the brink of death she started gathering the strength to get away from both.

“When I overdosed, my body was pushed out of a car and left for dead, and I was miraculously revived with Narcan,” she said.

With that second chance at life, Parker checked into a hospital six weeks later and began her recovery on March 9, 2012.

Parker is honest about what it took to recover, hard work, medical attention and a lot of help from agencies dedicated to providing support for those in recovery.

“I had to learn skills to learn how to live life differently and to be able to face those demons and deal with what had been plaguing me,” she said.

Parker said she started taking suboxone to address the chronic pain and withdrawal symptoms without leaving her craving more and dependency counselors and agencies helped her apply for disability until she was ready to get back on her feet.

Yet, with a criminal record, Parker said job prospects seemed slim. The notable exception was the field she already immersed herself in: Recovery services.

“Someone with lived experiences to help others, it’s so impactful,” she said.

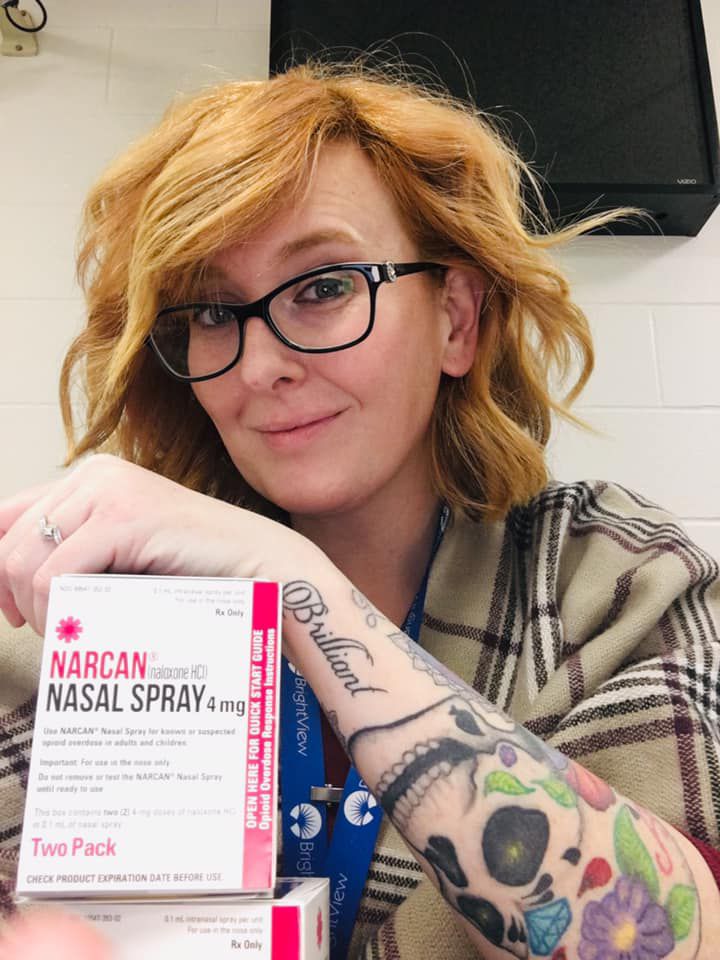

Many of the people who helped her, were also in recovery, so Parker figured she could do the same. She took a certification course to become a chemical dependency counselor assistant and started working as an Outreach Manager and Peer Recovery Supporter at Brightview Health, while also taking every opportunity to advocate or speak publicly about her own experiences.

“I started to realize that my story can help people,” she said.

Parker advocated for improved access to the life-saving drug Narcan and an end to the stigma surrounding addiction and by 2018, she said it felt like Ohio was turning the tide in the fight against opioids. Then came 2020.

“One of the most essential things that has brought us to a plateau in this epidemic is connection — human connection. That’s what’s needed for people to have hope, access hope and see that recovery is possible,” Parker said.

Yet when Ohio began to shut down in March of 2020, that connection became harder and harder to find.

“So many of these resources went to no contact, connection,” Parker said.

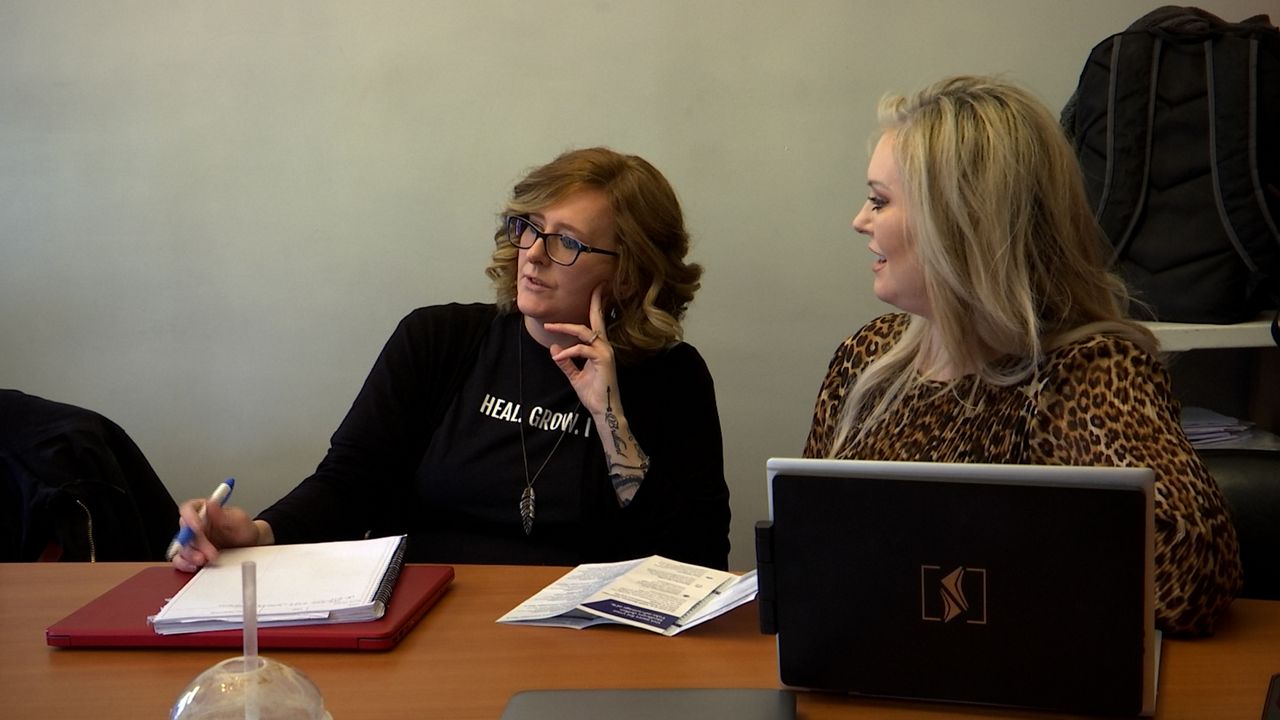

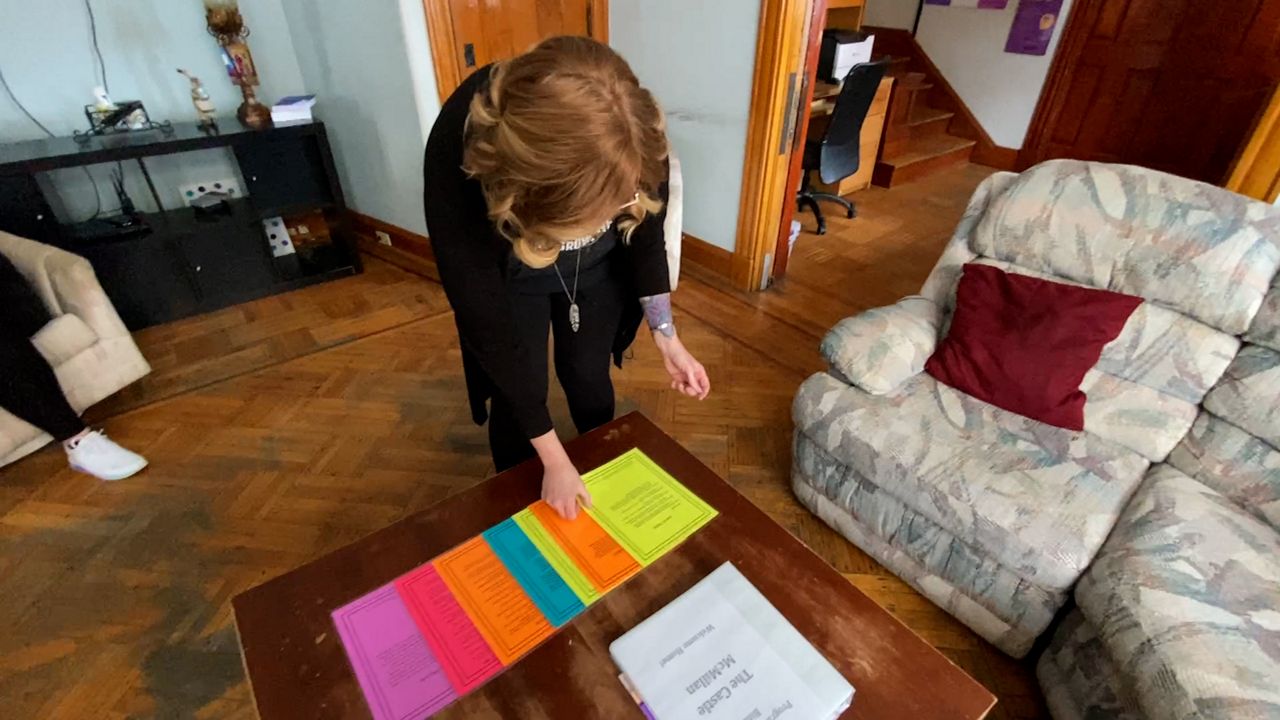

At the time, Parker was on the board at New Foundations Recovery Housing, a Cincinnati nonprofit providing transitional housing for those in the beginning stages of overcoming substance abuse disorder.

According to the executive director, Mikella Chrisman, much of New Foundations’ work relies on the camaraderie and peer support residents are able to build while living together, but in the beginning stages of the pandemic, all of that interpersonal interaction was difficult to manage.

“Our first priority was to keep residents safe,” she said.

Capacity across the eleven houses declined and Chrisman said even more left when some received delayed unemployment checks and stimulus money as lump sums and lacked support to resist the temptation to turn back to drugs.

“We had one guy who got an $8,000 check, left and overdosed,” she said.

That’s when Parker decided to take on a more active role at New Foundations. She became an outreach and marketing manager in 2021 aiming to get the houses back up to 75% capacity within six months.

“Just over Christmas time we were full,” she said.

Parker said much of her work has involved using her community connections to remove barriers for residents and community partners, allowing them to connect again. She worked with Chrisman to allow those on Suboxone or Methadone treatment who were previously excluded from recovering housing into the program.

“I’m very proud that I was able to come here with a goal in mind and set out to accomplish that goal and we did,” she said.

Now coming up on 10 years into her own recovery, Parker said sobriety just feels like normal life, though she said she works hard to remember where she came from.

“I think that’s why I work so hard to do as much as I can to be a good mom today,” she said. “I think I go a little overboard with trying to be, you know, super mom, but it’s a blessing.”

She said her daughter has never known the Parker who was fighting for her life in active addiction and she never wants to take that for granted.

Without life-saving help, Parker said she never would have gotten the chance to see this normal life, so Parker said she’ll never stop working to help others find the same path.

“There’s a beautiful life on the other side of this, but you have to work hard at it,” she said.