OHIO — Any city contending with the challenges of police reform has its story, a key moment or a tragedy that signaled the urgency for needed change.

In Cleveland, it was in 2014 when 12-year-old Tamir Rice was killed by police while playing with a toy gun. In Cincinnati, it was more than 20 years ago when police killed 19-year-old Timothy Thomas.

Two cities in the same state, dealing with the same issue: a lack of trust between the police and the community, and especially communities of color. It’s a tightrope between the need for police protection and the sentiment that the system doesn’t work the same for everyone.

Both cities are working on reform, with different approaches on how to do so.

Different cities, different approaches

"A pattern of excessive use of force": that’s how the Department of Justice described the actions of Cleveland police in 2015, as it mandated a consent decree. This was after the feds also stepped in back in 2004, to demand certain reforms.

For some, like Lewis Kats, the co-chair of the Cleveland Community Police Commission, this consent decree falls short.

“I don’t think we’ve had the progress that seven years and millions of dollars spent on the consent decree should have produced.”

A drive down I-71 offfers some perspective.

Rev. Damon Lynch, a lifelong Cincinnati resident, said he sees generational trends in the calls for police accountability.

“People in 2020 in the streets were about 20 years old,” said Lynch, pastor at the New Prospect Baptist Church. “Some of them weren’t even born when we had our time in the streets.”

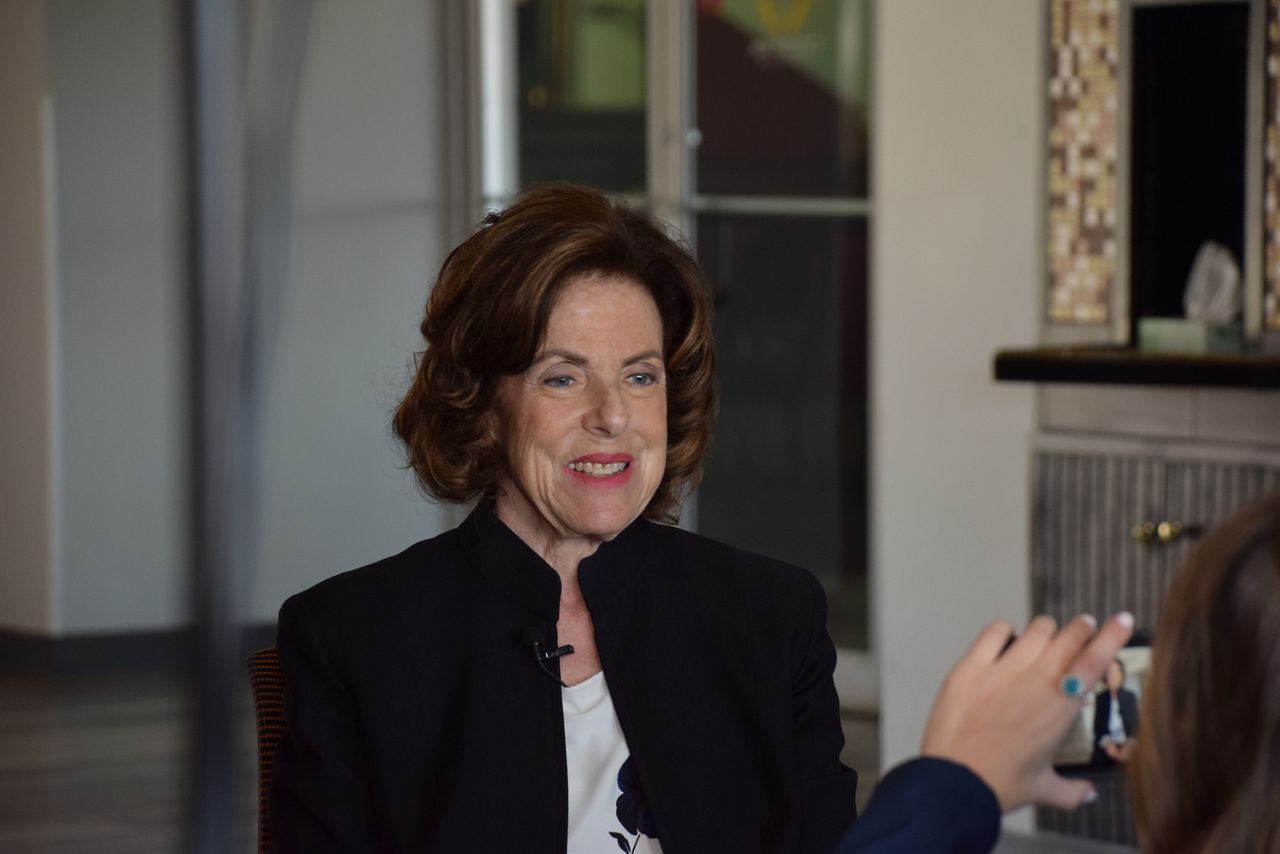

While those protesters hit the streets 20 years ago, court cases had piled up on U.S. District Court, Southern District of Ohio Judge Susan Dlott’s docket.

“At all times I had at least five or six use of force cases against the police department,” she said.

Civil rights attorney Al Gerhardstein said Cincinnati found a different approach. It was in 2001 that citizen groups extended an offer to the city that changed the community-police relations model.

“We’re inviting you to enter into a collaborative process,” Gerhardstein said. “The city was considering that effort—that whole idea—when Timothy Thomas was shot, and the city blew up.”

Every collaboration needs a spark.

Judge Dlott gathered all sides, all parties, in one room.

“I knew the only way to get it done was to keep everybody there," she said. “I paid for all the food that all these 30 people ate, every day, for two weeks.”

In Cleveland, there is no Judge Dlott to ensure all sides hear one another.

A consent decree versus a collaborative agreement

A Consent Decree is esentially a manditory to-do list from the Department of Justice. The feds instruct the departments to make changes to protect fourth amendment rights.

The Cleveland decree established the community police comission. This commission had no power for enforcement and no role in ensuring a positive shift with the police chief and mayor remaining in charge

A Collaborative Agreement includes a variety of parties, working alongside police, to improve community and police relations. This agreement is not mandated by the Department of Justice.

The City of Cleveland is still searching for a route to effective police reform.

“Nothing stopped," said LaTonya Goldsby, president of Black Lives Matter Cleveland. “Even with the consent decrees in place, we still have folks losing their lives to law enforcement.”

That’s why police reform advocates like Goldsby fought for Issue 24 in 2021.

Down in Cincinnati Teresa Theetge, the interim chief of the Cincinnati Police Department, embraces the collaborative change in her city.

“We are different because of our history, because of what the collaborative has had us doing the last 20 years,” she said.

Cody Thompson contributed to this report.