April DeSimone and Marcellus Murray had a vision in mind when they purchased their home in Trenton, New Jersey.

But standing in their basement, surrounded by the ripped up concrete and plumbing scraps, their dream can seem a long way off.

“Tens of thousands of dollars to do this,” DeSimone explained, “and we have to do more.”

From the corroded pipes to the water damaged walls, the sheer scale of this home renovation would likely send most homebuyers running.

Murray remembers his reaction to discovering the home’s underlying issues.

“I came down to the basement. There was water everywhere and I screamed, ‘Hey bro!”

Thinking about it now, the couple chuckles. Still, they say the scope of the problem is no laughing matter.

“I was like, ‘this is a money issue,” said Murray.

But DeSimone and Murray are on a mission to restore this one-time neighborhood showpiece and make it affordable for the everyday Trentonians that have long called this working-class community home.

“So this house is worth $500,000 now” explained DeSimone. “Once all the improvements happen it will be worth $900,000” which makes it even more unaffordable.”

The couple says comps put the future value at as much $1.7 million as the neighborhood around it changes – even further out of reach in an area where census figures show the median income is just over $47,000 a year.

By putting the home in what’s called a perpetual purpose trust and taking just one quarter of the equity for themselves, DeSimone says it can remain affordable forever.

“The trust holds the asset.” explained DeSimone. “We walk away with 25% of the $900,000. Now the person that comes behind us, rather than at 15 years, having to produce $1.7 million to live on this block, all they're producing is what that 25% value was.”

In other words, the next homebuyer will be able to purchase the home for just $300,000.

“The next family will be able to come in and have access to it at an affordable rate.” said Murray.

It’s a deliberate push back on the long-term effects of redlining – a discriminatory housing practice that denied loans or investments in certain neighborhoods because of the race or ethnicity of its residents.

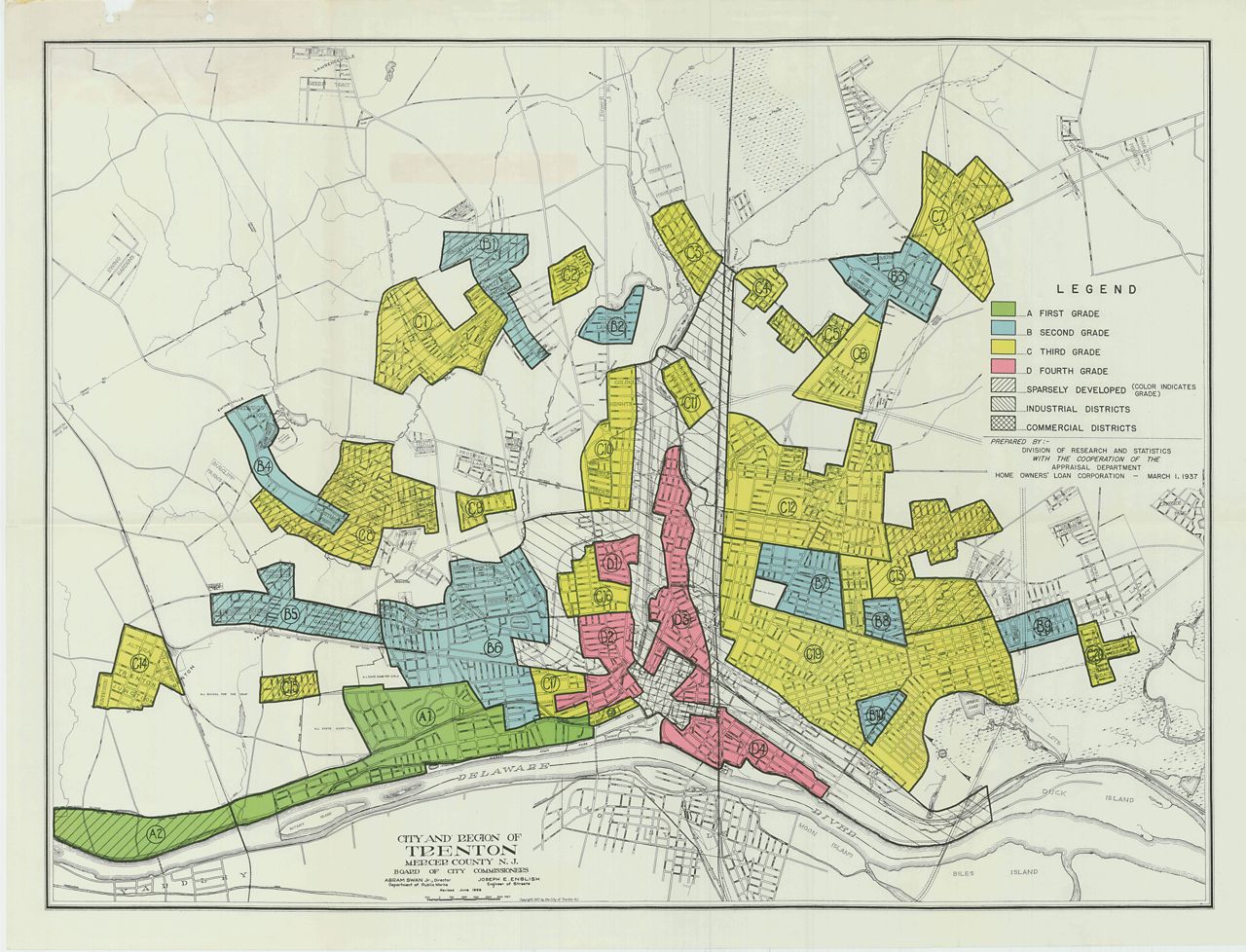

“They used four primary colors – green and blue, for the areas that were nicer, yellow for areas that were declining, and then red for neighborhoods that they considered hazardous,” said Jason Richardson, the senior director of research at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

Richardson explained how the value of a neighborhood was determined.

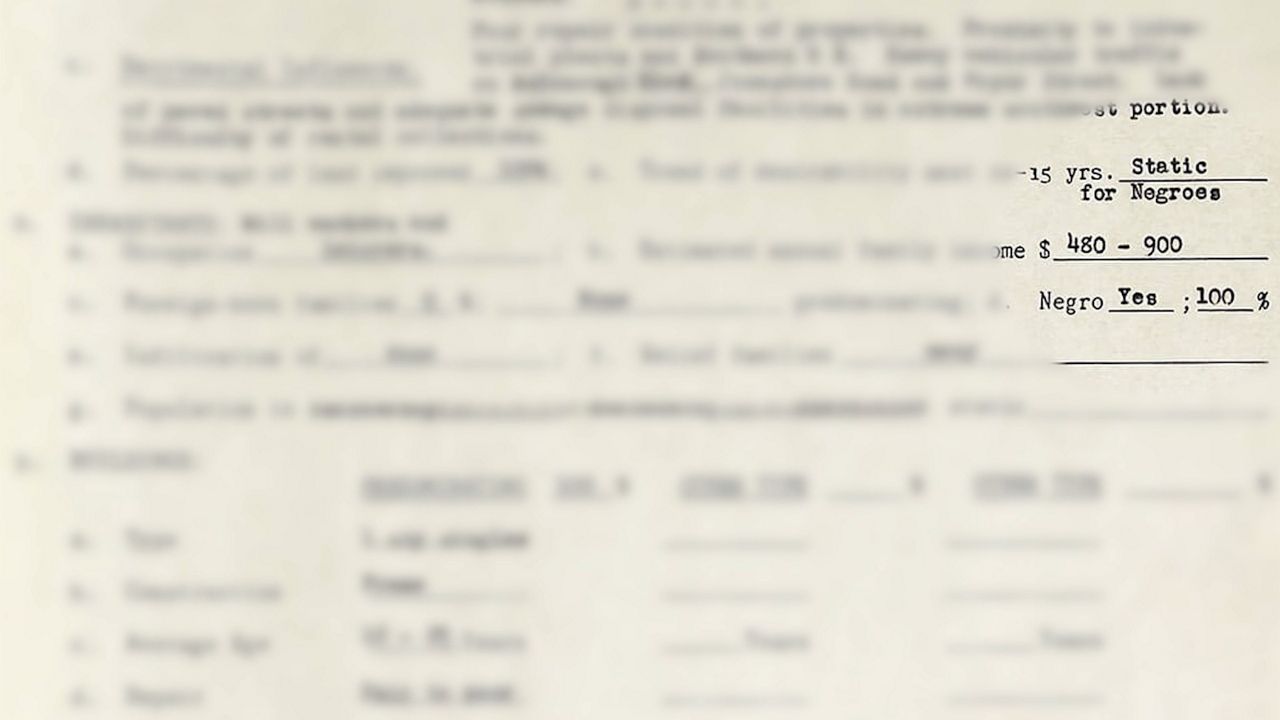

“What can get you redlined? Industrial facilities, too many people who weren't white, North European descent, but born in the U.S. Immigrant groups they didn't like, especially immigrant groups that were not North European, but especially African Americans.”

Forms filled out by redlining examiners at the time included a line specifically for noting the presence of Black families in the area.

DeSimone and Murray both grew up in New York City and saw the effects of the policy firsthand.

“In those communities, it was very visceral. Not only is it you see the decline of a community, but you begin to see people moving away and the disinvestment,” DeSimone remembered.

Although redlining was officially outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the impact of the policy is still felt today.

“We still see mortgage lending, business lending, bank branch locations. Anchor institutions like schools, hospitals not going into redlined communities,” said Richardson.

These lasting effects pose a challenge to prospective homebuyers.

DeSimone is the co-founder of Undesign the Redline – at traveling exhibit showing how the policy persists even today. She and Murray say despite their expertise and income, they struggled to obtain financing to buy this home.

The couple was required to provide individual divorce decrees – something Murray says he had never been asked for before. They were also asked to provide costly documentation about the condition of the house.

“They wanted an as-built. If you don't know what as-builts are, it's basically a blueprinting of the house which costs, what, $30,000?” said Murray.

The whole process was frustrating for DeSimone.

“So when we get an approval letter on what we have the buying power to buy, and we choose to spend it back in our communities, and then when we make that choice, there really isn't a pipeline that allows us to do that,” she said.

The couple is not alone.

“There are still fewer mortgages going into the redlined areas, and there's a bunch of reasons for that. First of all, the houses are worth less,” said Richardson. He explained that lenders have little incentive to make smaller loans, because they earn more off the interest on larger loans.

These types of hurdles often box local buyers out of the market, making these neighborhoods fertile ground for wealthy development companies looking to flip for a tidy profit.

“It creates displacement in our communities,” said DeSimone,” or gentrification.”

Still, they says, they’re pressing on. They hope this model for accessing homeownership becomes a standard – a viable option for those long-denied access.

“I think if we're truly in a free market, we should have market choices that allow people's lifestyles to be met by different products and services out there,” DeSimone said. “And I think this is what we're doing.”