TEHRAN, Iran (AP) — Mohammad Reza Shajarian, whose distinctive voice quavered to traditional Persian music on state radio for years before supporting protesters following Iran’s contested 2009 election, has died, state TV reported Thursday. He was 80.

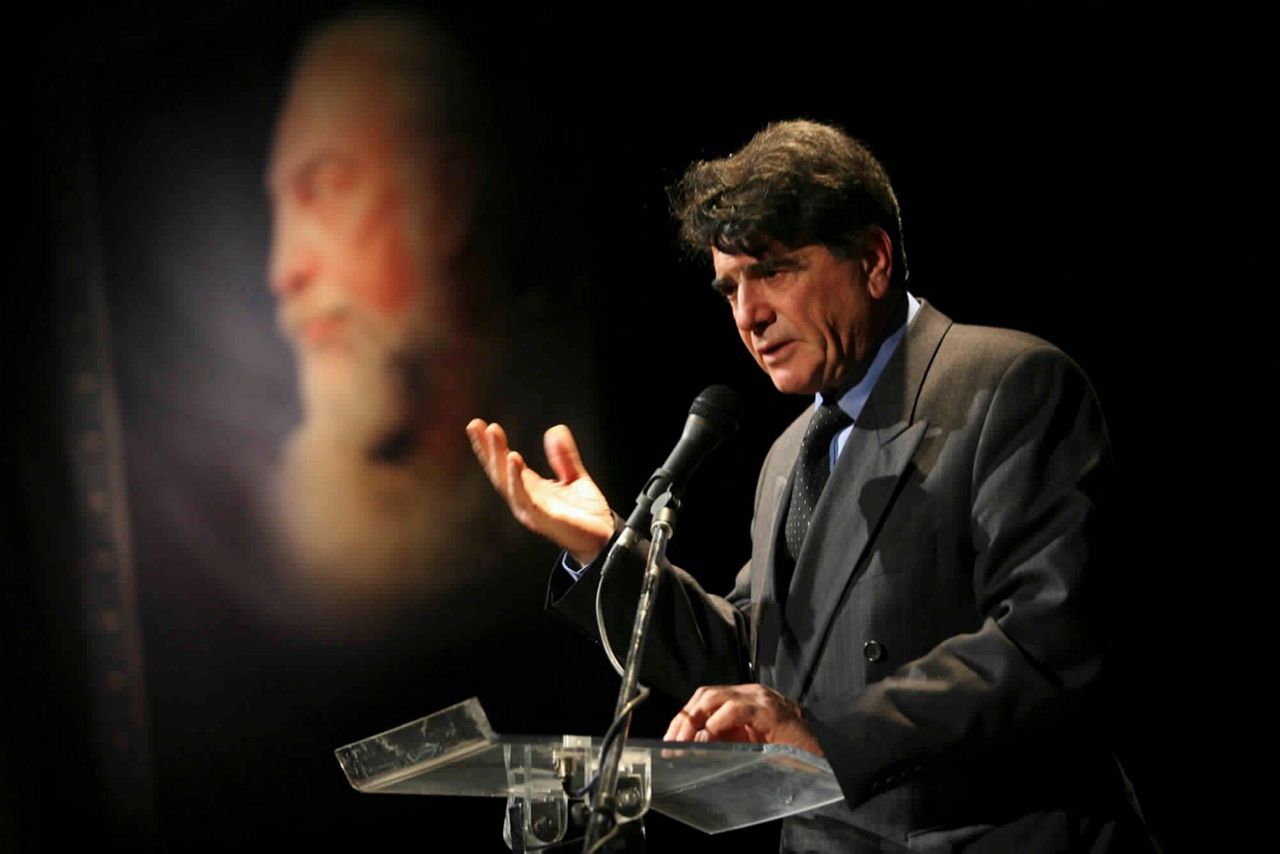

Shajarian enlivened Iran’s traditional music with his singing style, which soared, swooped and trilled over long-known poetry set to song. But the later years of his life saw him forced to only perform abroad, after he backed those who challenged the disputed re-election of hard-line President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad by telling state radio to stop using his songs.

“After what happened, I said ‘no way’ and threatened to file a complaint against them if they continued to use my music,” Shajarian told The Associated Press in 2009.

The TV report said he died on Thursday, following a long battle with cancer. Shajarian's son, Homayoun, tweeted that his father “flew” to meet the heavens.

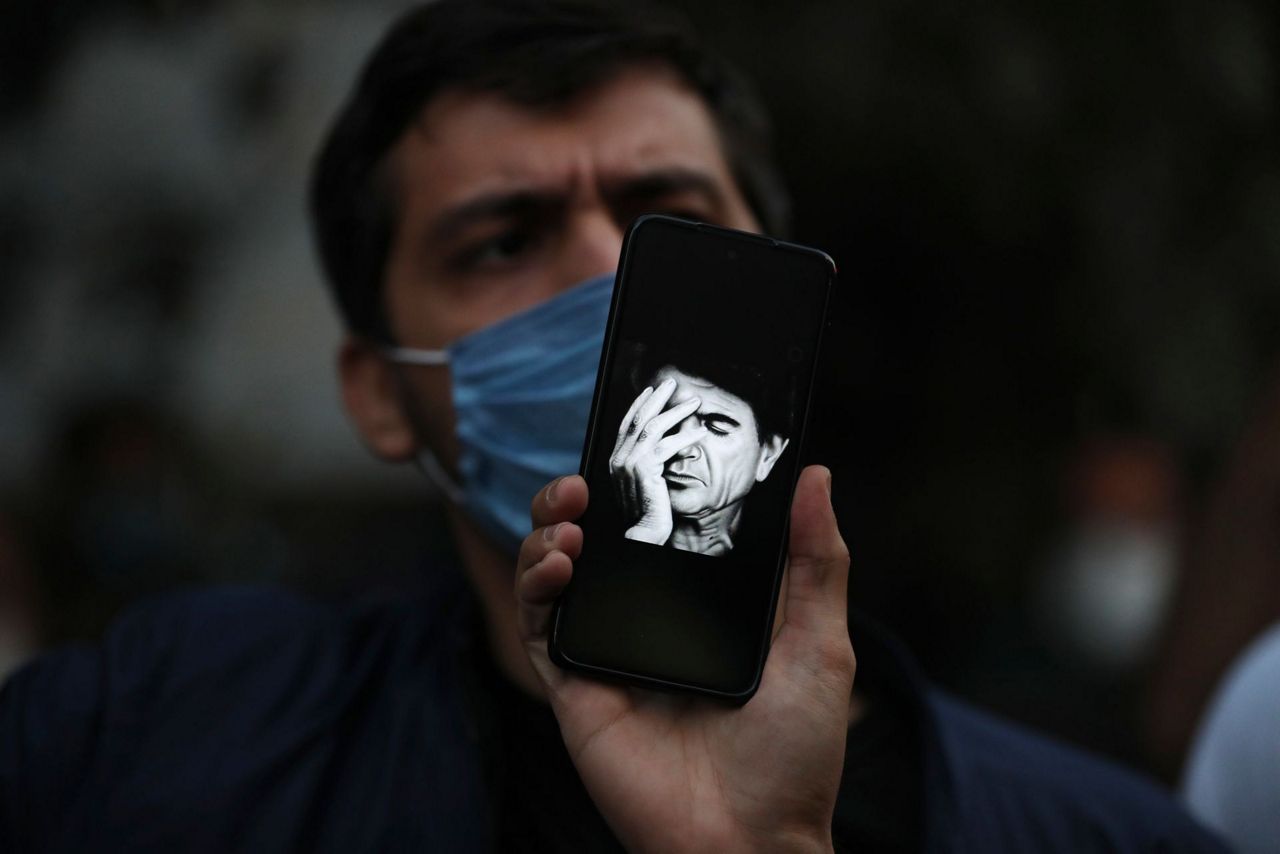

Within hours, Shajarian’s fans began gathering outside the Jam Hospital in the capital, Tehran, where the singer passed, several crying openly. One man sat on the pavement, his head in his hands, weeping. A teacher, 34-year-old Hasti Amini, said she was deeply saddened, describing Shajarian as “the people’s voice in difficult times."

“He was the great child of Iran. He was a big person and was very precious to us,” said another fan, Paria Hosseini. As night fell, the crowd lit candles in a vigil honoring the national icon.

“I am heartbroken,” said Mojtaba Yousefi. The 65-year-old car mechanic recounted how Shajarian’s songs played over the radio during the 1980′s Iran-Iraq war, bringing him and his comrades in the trenches “great comfort."

Iran's Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif tweeted his condolences, saying, “Maestro Shajarian was a great & true Ambassador of Iran, her children and—most of all—her culture." Iranian President Hassan Rouhani praised Shajarian for the “timelessness" of his songs.

In March 2016, Shajarian revealed to fans he had been receiving treatment for kidney cancer for some 15 years, both inside and outside of Iran. Highlighting his importance even then, Iran’s culture and health ministers announced they would follow his case.

Shajarian’s political stand surprised many in Iran, especially among the young who considered him a crooner of a past age. Though he once changed his name to avoid his conservative father’s opposition to his singing, Shajarian supported Iran’s movement against the American-backed shah. He resigned his position with Iranian state radio ahead of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.

After the revolution, it was Shajarian’s powerful voice on the radio that sang a prayer before sunset during the holy month of Ramadan, when observant Muslims fast from dawn to dusk. He sang it a cappella, like a call coming from a mosque minaret, with teeming emotion that raised goosebumps even through scratchy radio broadcasts. In sold-out concerts, fans pelted him with roses.

Supported by the apparatus of Iran’s cleric-run system, no one expected to hear his voice rise to support the opposition in the unrest surrounding the 2009 balloting. At the time, Ahmadinejad won a contested vote count that sparked massive protests and a security force crackdown that saw thousands detained, dozens killed and others tortured.

In September 2009, just months after the election, Shajarian sang “Zaban e Atash o Ahan,” which translates from Farsi as “The Language of Fire and Iron.”

In it, the singer pleaded: “Lay down your gun. Come, sit down, talk, hear. Perhaps the light of humanity will get through to your heart too.”

Shajarian then told state radio to stop using his songs, which they did. Suppression of artists had been common following the Islamic Revolution, though the 2009 crisis brought on a crackdown unseen in years.

“It’s much greater now because of the stand most of the artists have taken against them,” Shajarian told the AP in 2009. “For now, they’re moving very calmly. But in the future, I know there will be a confrontation between the artists and this government.”

In the years that followed, Shajarian performed traditional music for Iranians abroad and later returned to Iran to teach singing to many of his adoring fans.

Shajarian was born in 1940 in the religious city of Mashhad in northeastern Iran, some 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) east of the capital, Tehran. During his childhood, he got his start in singing through reciting the Muslim holy book, the Quran.

Throughout his life, he received a series of accolades, including awards from the United Nations' cultural agency, UNESCO. In 1999, the agency gave him the Picasso Award and in 2006, he received its Mozart Medal in honor of his contributions to the world of music. Shajarian also worked to create new instruments, similar to those played in historic Persia.

Even near the end of his life, Shajarian kept a sense of humor, appearing in an online video marking the Iranian New Year of Nowruz sporting a shaved head and referring to his cancer as a “guest” in his life.

“I am familiar with this guest for the past 15 years. We are friends and I cut my hair based on its order to reach an understanding,” he said. “After that, I will come back and will continue my artistic works.”

Upon the news of Shajarian's passing, many Iranians offered their condolences on social networks. The official IRNA news agency called Shajarian a “unique" artist. For the first time in over a decade, state TV showed file footage of the singer.

Later Thursday, Jam Hospital said Shajarian's body was taken to the Tehran cemetery, in preparation for transfer to Toos, where he will be buried, a town near Shajarian’s birthplace of Mashhad in Khorasan Razavi province.

When news of the burial place filtered down to the crowd outside the hospital, some started chanting against the decision, alleging the family had picked the location under government pressure.

Shajarian's son Homayoun, a singer like his father, denied this and begged the crowd not to turn the gathering into a political conflict.

"Art is more respectful than politics,” he said.

___

Associated Press writer Jon Gambrell in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, contributed to this report.

Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.