CINCINNATI – Macon Bolling Allen became the first African American licensed to practice law in the United States in 1844, a full 18 years before the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation. During his life, Allen would also go on to become the first Black man to serve as a judge.

What You Need To Know

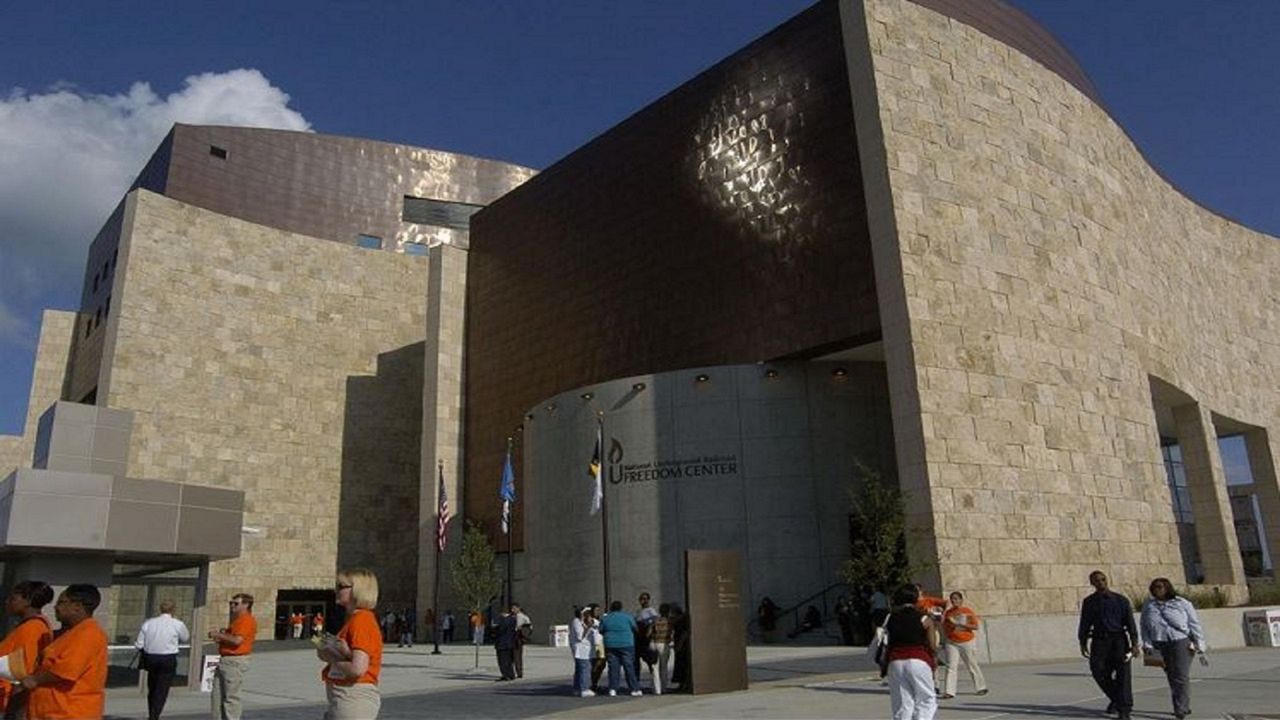

- National Underground Railroad Freedom Center tells the story of the first African American lawyer in the U.S.

- Macon Bolling Allen received admission to the Maine, Massachusetts bars and also served as a judge during his career

- Allen's legacy has empowered young African Americans across throughout the country to pursue legal careers even if they didn't know it

- Today, there's a push to get young people to pursue careers as lawyers, judges

Despite the significance of his accomplishments and impact on the country’s legal history, in many circles, Allen’s name has been lost to time.

Given many of the perceived challenges still facing the country’s legal system, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center and other organizations are using Allen’s story to help promote the importance of diversity in legal occupations such as lawyers and judges. And to increase diversity in “a legal system still suffering from issues of systemic racism,” according to the Freedom Center.

Now through March 31, the museum in downtown Cincinnati is hosting the exhibit “Macon Bolling Allen: The First African American Lawyer in the United States.”

“We know how important representation is, and that includes legal representation,” said Woodrow Keown, Jr., president and COO of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. “ In a criminal justice system that continues to be plagued by systemic biases, we need Mr. Allen to inspire greater diversity and better representation in the courtroom even 180 years after he was first licensed to practice law.”

Allen was born in Indiana in 1816. He later moved to Boston before settling in Portland, Maine in 1844. It was in Maine that Allen began studying law and worked as a legal apprentice to Gen. Samuel Fessenden, a local abolitionist and attorney.

According to the Freedom Center, Fessenden advocated for Allen’s admission to Maine’s bar. But Allen’s admission was initially denied based on the grounds he was “not a legal citizen” because he was African American. Allen persisted and ultimately prevailed, earning admittance to the state bar on July 3, 1844, becoming the first-known practicing African American lawyer in the country.

Becoming an attorney was merely the first of Allen's trailblazing accomplishments. He became the first practicing African American lawyer in Massachusetts (1845), the first Black man to become a justice of the peace (1848), and he helped found the first all-African American law firm with William Whipper and Robert Elliott in South Carolina (1868).

Despite his historic accomplishment, Allen still faced many challenges. The Freedom Center said Allen struggled to find clients in predominantly white Portland, Maine, where much of the Black population was unable to afford representation.

Allen moved back to Boston to seek better job opportunities. Following the Civil War, Allen moved to Charleston, S.C., to serve the legal needs of formerly enslaved people in the south.

He was appointed a criminal court and probate judge in Charleston County in 1873 and 1876, defeating a white incumbent for the position. Following the end of Reconstruction in 1877, Allen moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked for a firm called the Land and Improvement Association.

Allen passed away in 1894 as one of the most accomplished attorneys of his time, regardless of race.

The situation today

While his credentials are second-to-none and few can argue the historic nature of many of his professional feats, Allen is far from a household name today.

Hamilton County Judge Nicole Sanders said she hadn’t heard of Allen prior to being reached for this story. A lawyer by trade, Sanders said she’s taken several Black and African American studies courses over the years, and Allen’s story was never told. She also never recalls hearing his name while a student at the University of Cincinnati College of Law.

That’s part of the reason why the Freedom Center wanted to host this exhibit. One of the signature items on display is an attachment of a bond signed by Allen in 1878 while he was a probate judge.

”We were fortunate that Ken Parker, who has long been a friend of the Freedom Center, loaned us this document, which spurred us to tell the story of Mr. Allen,” Keown, Jr. said, president and COO of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. “Sometimes, it takes an artifact like this to help you tell a story.”

While he doesn’t have a direct connection to Cincinnati or Ohio, Allen’s actions and legacy continue to positively affect African American attorneys and legal professionals across the U.S.

Remington Jackson, president of the Black Lawyers Association of Cincinnati (BLAC), said Allen “literally paved the way for every African American attorney that practices today.”

“As we stand on the shoulders of the giant that is Mr. Macon B. Allen, we must recognize that we are far from the mountain top of diversity, inclusion, and equity that so many have fought for since our first Black attorney,” Jackson said.

In 2021, data from the American Bar Association found that Black attorneys made up roughly 4.7% of all lawyers, which decreased slightly from 2011, when Black attorneys made up 4.8% of attorneys, per BLAC data.

The data among leaders in law firms is even lower. Nationally, less than 3% of law partners are Black and only 3% of registered attorneys in the state of Ohio are Black. Of the 242 total partners in Cincinnati, 4% are people of color and even fewer (1.65%) are women of color, according to data from BLAC.

Jackson called the numbers disheartening. He said the numbers don't depict the number of attorneys who leave the legal profession because of inhospitable workplaces, "microaggressions and more overt racism, such as court staff mistaking them for a defendant rather than a lawyer, or the assumption that they were simply a diversity hire."

Sanders, who runs the Drug Court in the Hamilton County Court of Common Pleas, said she’s seen firsthand the importance of having a diverse and representational legal system during her 20-year career. Not just attorneys either; she means at all levels of the legal system – from police officers to the judges presiding over trials.

Sanders has been an elected judge for just a little over a year, but served as a judicial officer as a magistrate for seven-and-a-half years. She also practiced as an attorney for the city of Cincinnati, working as both a prosecutor and a solicitor during her tenure there.

“Ideally, your judicial officers and the attorneys represent a fair reflection of the community as a whole, diversity of color, but life experience, education, community experiences,” she added. She doesn’t mean just race, or color either. She means gender, socio-economic backgrounds and other socially defining characters.

“Those things can help build a sense of trust and help people feel as though they’re being heard and understood,” she added

Sanders said she hopes her wearing a robe brings a mixture of “inspiration” and “confidence” into the community. She wants people to look at her on the bench and know anything is possible. She wants those who may appear before her to see her as someone who “may be able to understand” their life experiences.

Jackson said it’s BLAC’s mission to bring equity to the legal profession. The group’s leadership works with national, state and local bar associations to solve problems specifically facing African American lawyers.

BLAC is also involved at the community level where they support youth programs and partner with other bar associations and community organizations to provide free legal clinics and educational forums.

Jackson feels he has managed to get to where he is today in large part because of Allen’s legacy. He feels it's now the job of BLAC and other organizations to help finish what he started.

“Our mission is to ensure Judge Allen’s legacy lives on in our efforts to diversify the legal community,” he said.