COLUMBUS, Ohio — In Ohio, efforts at the local and state levels are trying to improve the low COVID-19 vaccination rate among Black residents, which officials said is a major reason why Black Ohioans have been hospitalized with the virus at higher rates than white residents.

What You Need To Know

- Health disparities have been exacerbated by the pandemic and the vaccination rate among Black residents remains low

- Some Ohio officials say door knocking campaigns are needed to raise the vaccination rates in vulnerable communities

- The Ohio Controlling Board approved requests to direct stimulus dollars toward reducing COVID-19 health disparities

Health officials are working on data-driven approaches to try to make the vaccine more accessible to vulnerable populations. The efforts involve partnering with community organizations, knocking on doors and offering the vaccine with mobile units.

Last week, the Ohio Department of Health received approval on a request to use $17 million in federal relief funds to “support the state's COVID-19 response to reduce health disparities among Ohio's most vulnerable communities.”

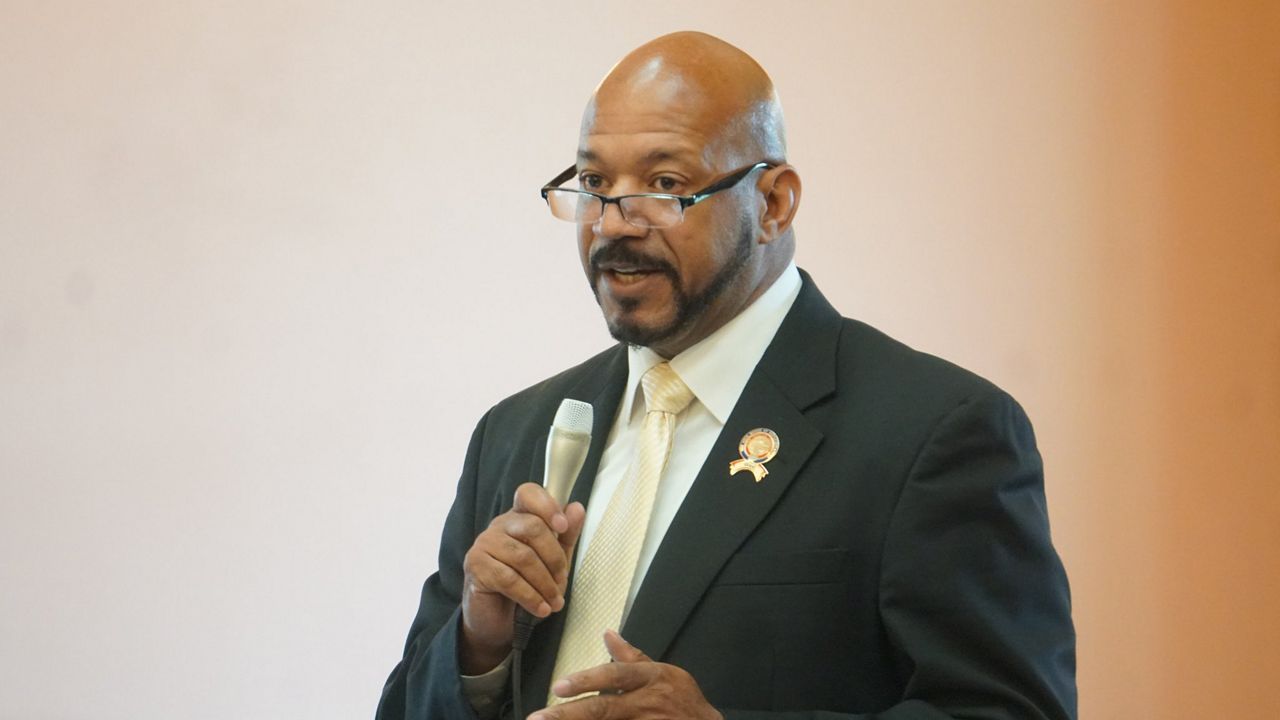

State Rep. Thomas West, D-Canton, assistant minority leader and president of the Ohio Legislative Black Caucus, told Spectrum News these funds will be critical to improving health equity in Ohio and addressing vaccine hesitancy among Black residents.

“The pandemic has disproportionately affected African-Americans and minority populations on every front,” West said. “We've been crying for these dollars for a long time now, so I'm excited to see that they're finally coming down the pike.”

The funds approved by the Ohio Controlling Board will be used to support transportation initiatives, workforce development for health care and social service providers that work with vulnerable populations and new investments in data systems related to health and social vulnerabilities.

“Obviously, health disparities have been around for a long time, and the gap had continued to widen, despite some of our previous efforts, but these dollars that are put forth by the controlling board, $17 million in FY22, definitely will help to address a lot of the health disparities that we see that have been exacerbated as a result of COVID-19,” West said. “That's a pretty big chunk of change.”

The request was approved alongside other requests from the health department to purchase COVID-19 home tests that will be distributed to residents at no cost. In January, the controlling board approved requests from the health department to use tens of millions of dollars in federal stimulus funds for mobile vaccination units and vaccine education campaigns.

The state’s vaccine dashboard shows that 48% of Black residents in Ohio have received at least one vaccine dose, which compares to a rate of 57% for white residents.

West said that previous vaccination campaigns in Ohio have been too impersonal.

“We've done a lot of talking. We've done a lot of TV stuff, but now it's time to get our feet on the street, knock on doors, find out and assess what people's needs are,” he said. “Sometimes you need a personal touch to help people move along the way, and that personal touch has been lacking.”

According to state data, the rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations since the pandemic began is about 50% higher for Black residents than white residents, despite Black Ohioans being younger on average — older age is typically associated with greater risk.

In Hamilton County, the gap is even wider, according to Health Commissioner Greg Kesterman. He said last week the rate of hospitalizations among Black residents is twice what it is for white residents, though the difference in COVID-19 death rates between the races isn’t nearly as wide.

“We know that the No. 1 way to stay out of the hospital has been to get vaccinated, and we know, unfortunately, that the rate of vaccination for those that are Black, or African-American has been lower than that for white individuals, and so we continue to work to make sure that we are able to get vaccines out into the communities where minority populations live,” he said.

Black residents are also more susceptible to the virus due to higher incidence of chronic diseases and other factors related to social determinants of health, Dr. Charles Modlin, MetroHealth’s medical director of the Office of Equity, Inclusion and Diversity, said in a recent video message.

He said that these vulnerabilities include not having health insurance or good health care opportunities, living in dense areas, lacking access to healthy foods and working in high-risk jobs that can’t be done remotely.

State officials plan to share more information in several weeks about a vaccination project in the planning stages that will involve new incentives for getting the shot and targeted vaccine clinics in communities where uptake has been the lowest.

Data analysts are identifying census tracts where additional vaccination clinics should be offered, using vaccination rates and demographic data.

Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb said last week that his administration will be working with community organizations “to knock on doors, use our schools, and really meet our residents where they are, so they can get access to the vaccine.”

He said the Cleveland Health Department will use mobile vaccination units to make the vaccine accessible in vulnerable communities, and Bibb said they will partner with grassroots leaders who are trusted in neighborhoods with low vaccination rates, directing a “very intentional communication campaign” toward tackling mistrust and misinformation about COVID-19.

“It's important for us not to reinvent the wheel, but to use those trusted organizations on the ground who can be that conduit for us to hit those hardest parts of our city,” he said.