CLEVELAND — A good bowler usually scores around 200 in a single game.

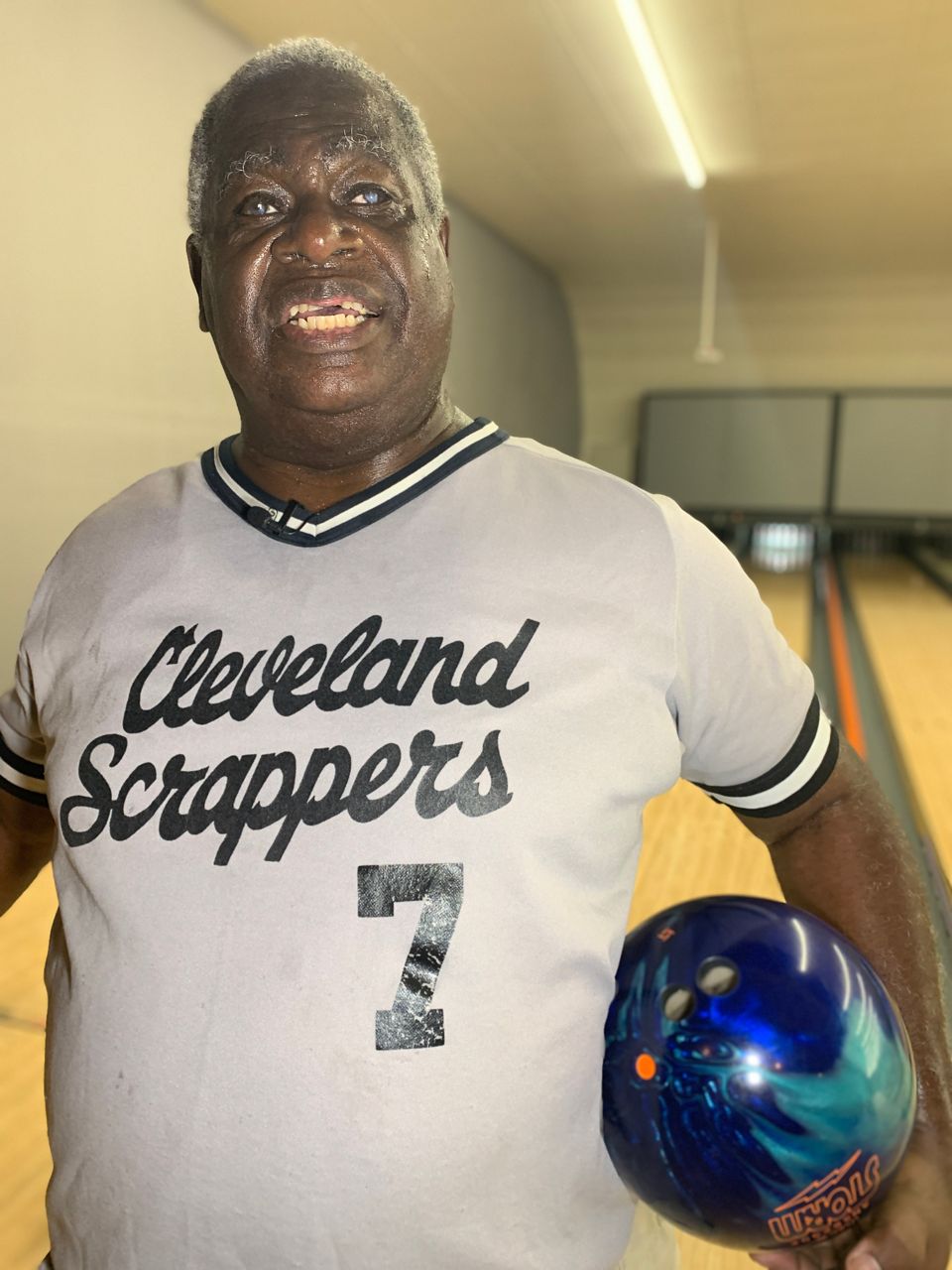

Wilbert Turner has a world record of 207 and he’s been blind since birth.

“I love competition,” said Turner. “I am a competitive person, whether it be sports, whether it's life, whatever it is. I put my best foot forward.”

Turner was born with nystagmus, weak optic nerves, among other disorders and his eyes never fully developed.

“I'm in a fog. I'm not in the dark. I'm in kind of maybe gray,” said Turner. “I'm very fortunate in some ways that I was born blind. And by being born blind, it was not an adaptation for me. It was a way of life for me.”

Growing up, he was fascinated by big trucks and wanted to be a truck driver. But because of his lack of vision, he had to settle for a desk job.

He worked for the Internal Revenue Service for 36 years. He married a woman who was also blind and provided a great life for her and their two children, and he currently has three grandchildren.

“Pretty much everything you've ever done, I probably tried it,” said Turner. “I think no matter what a person's disability is, or inability is, they should be afforded an opportunity. You have to show me that I can't. Because when you meet me, I believe I can. And that's the philosophy that I've lived with as a disabled person.”

Turner lives on his own and doesn’t let anything stop him.

He wrestled, swam and ran track in high school and now bowls.

Turner is learning bass guitar, plays baseball and travels.

“My experience is that the more you try, the better you get,” said Turner. “I was the first quality assurance program manager for the Internal Revenue Service that was totally blind in the United States. I hold the world record for totally blind bowling in the first international play. I was one of the first people to get inducted into the Beep Baseball Hall of Fame. So I have a few firsts.”

He didn’t choose the hand he was dealt, but he did choose to not let it get him down.

“I've learned to focus on the things that I can change and not dwell on the things that are outside of my ability to do anything about,” said Turner. “Take some risks in life. Even if you're not sure. If it's something you really want to do, try it. You'd be surprised, you probably can do a lot more than even you can imagine that you can do. But you have to give yourself the opportunity.”

Turner views the world through a different lens, but finds opportunities everywhere he can.

He said his lack of sight is not who or what defines him.

“Being a visually-impaired person, I have worked around things all my life so I'm not afraid to be adventurous or try to come up with an alternative way of getting it done,” said Turner.

Turner said the hardest thing as a visually-impaired person is to feel accepted and be included in society.

He has been an advocate for people with disabilities all his life.

He currently serves as the treasurer for the National Federation of the Blind of Ohio, works with the Cleveland Sight Center, is the fundraiser chair for the American Blind Bowling Association and is the former president for the Greater Cleveland Blind Bowling League.

There are really only two things he feels he’s missed out on in life: One is having his dream job of being a truck driver and two is seeing the faces of his family.

“I would love to look at my two daughters and my three grand boys at least one time in life and really get to see them, watch them smile, watch them do whatever it is they're doing,” said Turner. “I'd like to really know what they look like.”

At 67 years old, he still hasn’t given up hope because he says hope is all we have.

“It's difficult to say what's impossible, what's even improbable,” said Turner. “So for that reason, I have hoped that someday maybe someone may make a discovery where they can maybe regenerate cells. And that might strengthen my eye . . . And who knows, I might still get to drive the truck that I dreamed about as a little kid.”

Although there is currently no cure for Turner’s blindness, Dr. Richard Hertle from Akron Children’s Hospital said there have been expansive strides made in research and treatments for visually impaired people, including treatments for groups of diseases that weren’t possible decades ago.

“There are specific surgical treatments for rare diseases, where before, patients grew up without the hope of doing things like driving, and now 60%-70% in some diseases after surgical treatment, these patients can drive,” said Hertle. “We haven't made much inroads into those diseases that are the result of inherited diseases or genetic diseases. But the horizon for treating those is bright and near. Because we at Akron children's, along with other centers around the country will begin gene transfer therapy for inherited diseases of the retina and optic nerve. There's already an approved gene transfer therapy for one disease right now. And we see many more coming down the pipeline.”

Hertle is the director of the Children’s Vision Center and Chief of Ophthalmology at Akron Children’s Hospital Medical Center. He’s also an advocate of the Cleveland Eye Bank Foundation, a philanthropic, independent association that raises funds for research to preserve and restore sight.

Hertle said a misconception about the visually impaired community is that they can’t live a fulfilling life and that they can’t do the same things as those who have full vision.

“I would say that anyone who feels that somehow visual dysfunction interferes with life has not spent a lot of time around people with visual dysfunctions. I have patients who are scholar athletes, who are artists, internationally famous, who are sculptors, painters, musicians, and some who still live in the basement with their parents, like every single child in the United States, I don't see them as any different.”

He said it’s a highlight of his clinical career to watch diseases that were once incurable, be cured and watch diseases that were once untreatable now be routinely treated. There's hundreds of causes of complete blindness at birth, but Dr. Hertle said even for those born with current incurable blindness, he remains hopeful for them as technology and modern medicine continue to advance.

“The knowledge we’re gaining from the field of genetics, and all of the bright people who are developing new technologies, I couldn't imagine that someday, some of my patients who were totally blind could drive. And someday, they may be in a driverless car by themselves, commanding the car where to go and being as independent as anyone else. So I think the combination of medical knowledge and technological advancements will allow patients with visual impairment to become much more independent over the course of their lifetime,” said Hertle.

Hertle said whenever he has the chance to speak to the public he tells them to not give up and that there is someone who cares about what’s wrong with their visual system or eyes.

“If you feel like you're not getting the answer. There are resources for you to go to, to try and get some different answers and opinions,” said Hertle. “Don't give up and don't be afraid to not stop.”

For more information on Akron Children’s Hospital and the work Hertle is doing, visit here.