CALDWELL, Ohio — In Noble County, compliance with Ohio’s mask mandate is poor, health officials frequently encounter hostility when they make contract tracing phone calls, and coronavirus conspiracies are popular, yet the county has maintained the lowest occurrence of COVID-19 anywhere in the state.

Residents and officials say a bit of good fortune combined with natural factors, particularly the lack of dense population areas, have spared this area in the rolling hills of Southeast Ohio from experiencing community spread of the virus.

Of the county’s 14,500 residents, only 27 people have tested positive for the virus or been identified as probable cases.

The village of Caldwell, the county seat, is home to the courthouse, the banks, two of the county’s schools, and a handful of shops and restaurants, which are mostly family businesses that have been around for generations servicing residents from the entire county.

Caldwell was a “ghost town” in the spring, says shop owner Richard Brienza of Mike’s Tire Shop, who does business in the town square. Hardly any stores were open. Some days there was not a single car on the square.

Now the village is back on its feet. Walking through Caldwell, you might even forget there is a pandemic.

“Everything is about as normal as I can remember,” said Brienza. “The virus hasn’t really had much effect on us.”

In Noble County, the restrictions that are so noticeable in other parts of the state, that some call “the new normal” are ignored there by residents and go unenforced by local officials. It’s more like the “old normal” in Noble County.

Brienza said he seldom sees anyone wearing a mask despite a statewide order that mandates them. He has only worn one once to go the doctor when it was required.

Tim Hayes, owner of Hayes True Value Hardware in Caldwell, leaves it up to his employees. If they want to wear a mask, fine, but most don’t. He told his staff to put one on if a customer asks, he said, but he estimates 95 percent of his customers come to shop without masks.

Shoe salesman Dick Saliba says he is a “genius.” His store was ordered to close for a couple months in the spring when retail operations were shuttered by the state, but he kept about half of his business. Everyone in town knows he is the guy for shoes. They called him when they needed a pair, and he let them into the store.

“People know me, and if they needed something, they’d call. I wasn’t going to turn them down,” he said. “I don’t get too worried about the virus because I’m a genius—I told you. I had customers. They’d call me and I’d come back down. I didn’t care.”

Shawn Ray, the county’s health commissioner, said he cannot be heavy-handed in his enforcement of statewide health orders.

While large events are still restricted in Ohio, the county has allowed some to proceed. Ray said he has side-stepped the state’s guidance and allowed some organizations to hold large events. If he were to veto all large events, he fears the activities would proceed underground.

The state’s 10 p.m. alcohol sales cutoff is adhered to in Noble County, and it is perhaps the most noticeable restriction here. But the rural county is not necessarily bustling with nightlife in a normal year.

Many of the establishments are open just until 9 p.m. or so, anyway. On Thursdays, per tradition, almost everything in Caldwell closes at noon.

More prevalent and more beloved than pubs in Noble County are its fraternal clubs, which are like a cross between a charity, a senior center, and a dive bar.

Ron Baker, 70, who is retired after 42 years with American Electric Power and was on a stroll through Caldwell, said other than the eight-week shutdown—which closed the Caldwell Moose, one of those members club where older folks gather for a drink and Yahtzee games and organize community service—everything has more or less stayed the same for him. He spends most of his time on the farm and lives comfortably off his retirement income and social security.

“In this neck of the woods, it’s life pretty much as it’s always been,” he said. “But I got a feeling that if the numbers would start going up around here, then people would look at it a little different.”

He is a Trump-supporting, gun-shooting conservative, but he says wearing a mask is not so bad, and he encourages others rural residents to give it a try for a month or two, and see if it brings the case numbers down. But Baker might be in the minority.

If there were not so few cases, Noble County would be exactly the type of place officials in Ohio say gives them worry, six months into the pandemic. As urban areas have seen the spread of the virus slow down, Gov. Mike DeWine says the outbreak is worsening in rural parts of the state where compliance with the mask mandate has been poor.

Noble County has staved off the virus so far. But the county is not totally lacking when it comes to close quarters gatherings spots—social clubs perhaps chief among them. School has started back up in person. The health commissioner worries about a nursing home in the county and the prison, Noble Correctional Institution, as possible deadly breeding grounds for the virus.

The county is yet to record a death, but it had a close call when an 85-year old and 90-year-old couple, retired language arts teacher Elnora Grant and retired Chevrolet metal inspector Michael Grant, became ill with the virus.

All the Grants can do is guess as to how they contracted the virus. The couple went to one church service a month before they got sick. Other than that, they just went grocery shopping and to the drug store, always with masks on. Elnora said they must have forgotten to sanitize something, or happened to pass too close to someone in the store.

As their illnesses progressed, they experienced more symptoms and more exhaustion. Elnora sat in a chair for three nights because she had trouble breathing while lying down.

“We didn’t eat or drink. We didn’t keep that up because we didn’t feel like getting out of bed,” she said.

When her husband did not get up for two days, she really started to get scared.

“Finally the second day, I said, ‘I'm sorry, but I'm calling the life squad.’”

Michael was released from the emergency room later that day because doctors said he was not in need of immediate care. Gradually, they recovered. Elnora said they are very blessed.

“The lord took care of us. I give him credit for it,” she said.

She wishes residents of her county would do what they are asked to do by health officials. It protects people like her and her husband, who can get very sick and could catch the virus from anyone in passing at the store.

The Noble County Health Department said it is struggling to convince residents that COVID-19 should be taken seriously. Some of the challenge is political, the health commissioner said. In rural counties like Noble the virus is widely seen as a partisan “charade.” Many residents reject any suggestion that they need to modify their behavior to slow the spread.

“Having the smallest number of cases hasn't made our job any easier,” Ray said. “We struggle with that pushback that this is not real.”

Noel McFarland, 82, a barber at a one-chair shop he has owned since 1964, has had a tough year. McFarland is like the town elder; he knows just about everyone and everything in Caldwell. He says he has the best perch in town, right on the Caldwell square. Residents passing by poke their head in to his shop to say hello and absorb a bit of his wisdom.

As he sits by the window of his shop with a stack of newspapers left-behind by customers, carefully rolling them into “furnace logs” that he gives to a long-time friend, McFarland explains he recently had rotator cuff surgery after a bad fall. Between the surgery and the pandemic, his shop has been closed half the year.

At the shop, he keeps a mask on hand for when he needs it. Generally, he sees little reason to wear one in Noble County with case numbers so low, but given all he’s been through, he said it is wiser to use the mask when he’s cutting hair than risk his license.

“The barber people want me to wear a mask and the barber people could cause me a problem,” he said.

It is a different story when he is in in Marietta, a city one county over. He wears a mask religiously there—not for the barber people, but for himself, because the occurrence of COVID-19 is much greater there in Washington County, and McFarland says he likes living.

Many Noble County residents say the state’s restrictions ought to be lifted in counties like Noble where the spread of COVID-19 is so low. McFarland disagrees because he knows that others are not as responsive to the case numbers as he is.

If the governor intends to keep restrictions in place like the mask requirement and the state’s 10 p.m. cutoff on alcohol sales cutoffs, those orders ought to be applied statewide, he said.

“We can’t let our guard down. If we let the guard down, it’s going to move in on us,” he said. “It’s got to be the same all over the state.”

If cases were to rise in Noble County, other residents would remain unphased. They have dug their heels and bought into the fight against masks, a culture war residents are determined to win. Noble County residents are like “rebels” when it comes to the pandemic, Brienza said.

Bartender Michelle Knight, 50, says she is about as rebellious as they come.

She explains she is a couple weeks into a boycott of Walmart because an employee told her to put a mask on.

“I don’t live in a communist country, I don’t need to wear a f------ mask. I’m sick and tired of political games,” she said. “I went to Walmart with my child and the Walmart b---- said I need a f------ mask. I won’t ever go to Walmart again. That woman’s a Gestapo Nazi.”

Knight’s viewpoint is extreme, but it is not a hard one to come by in Noble County. The mindset is exactly what makes the health department’s job here so challenging, Ray said. These sorts of comments are what contact tracers hear on the other side of the line when they are trying to make phone calls to figure out who needs to quarantine.

Knight was enjoying her afternoon on a day off at Oasis Bar And Grill off Highway 77, a dive bar where she pours drinks a couple nights a week.

Around 7:00 p.m., she said it was time to go down the road to “the Eagles,” another one of the members club which are popular in the county. At the Eagles, the company is familiar and the beer is cheap, discounted by annual dues. The club is a chapter of the Fraternal Order of Eagles, an international nonprofit.

Her crew of drinking buddies settle their tab at Oasis. Knight smokes a quick cigarette, and they hop on their Harleys headed to the Eagles.

Lots of residents distrust the government, she explains on the drive there, which motivates skepticism of the pandemic and fuels anger toward the state’s restrictions.

She inserts her member’s keycard and opens the door to the Eagles.

Inside the club, a group of members is looking for one more person to play Euchre, a card game. Members are ordering Budweisers hoping the bartender pulls out a rare white-colored can, a sign of good fortune if you are served one. A man is trying his luck at one of the three gambling machines.

Knight explains Noble County residents feel neglected. The county is poor. Jobs are hard to come by. Residents reminisce about the area’s heyday when a MAHLE factory that made bearings employed hundreds with good paying union jobs.

“There’s no work down here. We’re in Southeast Ohio. We’re in the land that time forgot,” she said. “Everything’s different in a small town. We live in a different world.”

Knight says the person who knows best how hard the county has been affected by the state’s restrictions is Davette Mitchell, a single mother who has been the bar manager of the Eagles for more than 12 years.

The bar is Mitchell’s life. Her kids basically grew up around the Eagles, and all the members know her kids—it’s like a big family, she said.

During the shutdown in the spring, Mitchell said she called every day to try to get unemployment, but couldn’t get through. She did not receive any money from the safety net program until after the bar had reopened. Now the 10 p.m. closing time is hurting, and the governor’s rationale for it does not make sense to her.

“It’s ridiculous we have to close at 10. p.m. We're a club, so it's the same people that's here every day, and we're all around each other,” Mitchell said. “We have a big chunk of people that come every day. They’re here at 5 or 5:30 p.m., and I still have them at closing. It’s nobody different coming in.”

DeWine has brought attention to social clubs as potential places where the virus can spread. In Summit County, 12 people tested positive and two were hospitalized after an outbreak at a social club.

The members clubs in Noble, which in addition to the Moose and the Eagles include chapters of the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, each attracts a devoted, unique membership, Mitchell says. The Legion has an older crowd, as does the Moose. Part of the membership at “the V” is a group of golfers who go there after their round to drink. They all give back to the community with volunteering and fundraising.

Mitchell says the Eagles membership includes two dozen Caldwell volunteer firefighters and another two dozen correctional officers of the prison, as well as a couple guys from the sheriff’s office. Some of the correctional officers do not get off work till 10:30 p.m., she said, so the bar completely loses that crowd’s business and tips, which Mitchell lives off to provide for her kids.

“We have the lowest numbers in the state, so I feel like when they did the whole 10:00 thing, they should have done it by county. Why hurt us? We're not spreading it,” she said.

Ray, the health commissioner, said his job became more difficult as the state reopened and restrictions loosened

“It's hard to believe, but as we were loosening up, the people got more and more upset and wanted to buck the restrictions.”

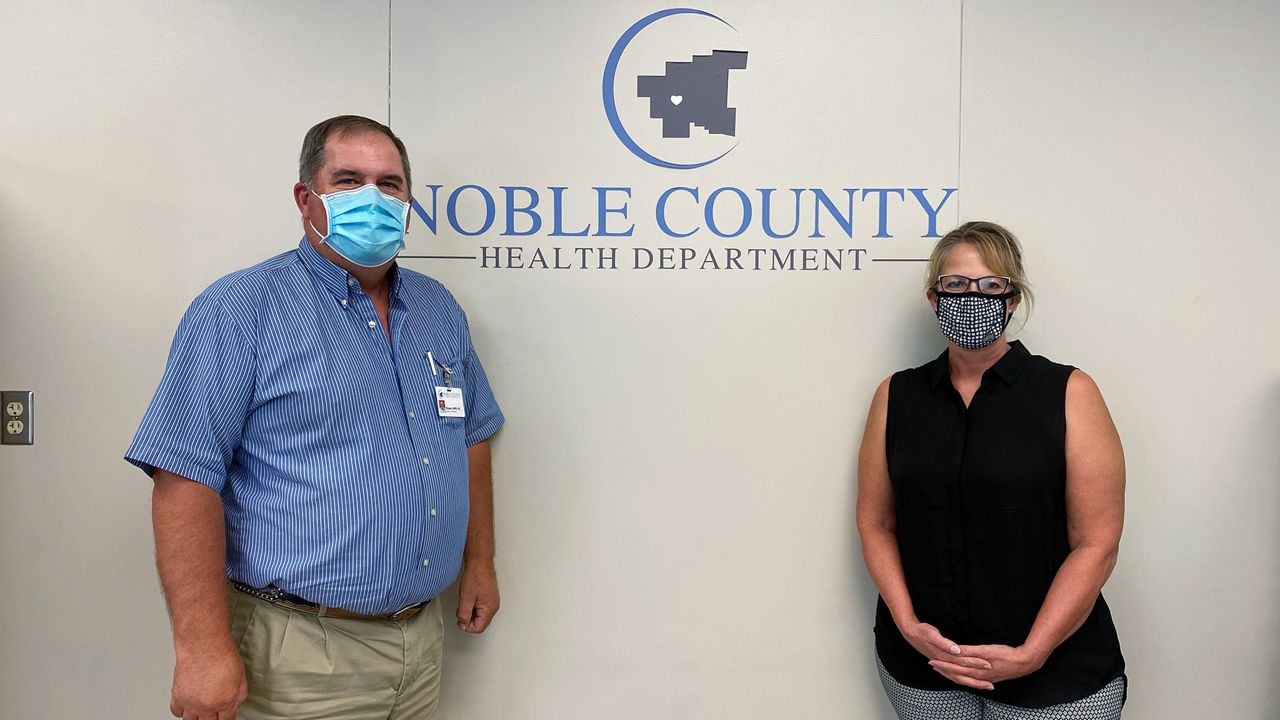

Shari Rayner, the health department’ director of nursing, oversees a small team of contact tracers that has contacted about 120 residents so far during the pandemic. About 30 percent of the time, she encounters open hostility.

“When you're talking about masks, when you're talking about social distancing, when you're talking about things like that, I'm finding that is a huge challenge for us right now,” she said. “Because we have such few cases, people think they shouldn’t have to comply with all the restrictions that the rest of the state does.”

On Facebook, the health department gets comments from users who Rayner says are getting their information from memes and using them to sow disinformation about the virus. It is usually the same people commenting, she said.

Time and time again, Rayner hears two claims she finds perplexingly misguided: 1) That the virus is a political game that will all be over in November—what that means, she is not exactly sure, but it is something to the effect that the true scope of the pandemic is being grossly exaggerated to hurt President Donald Trump, and 2) that if Walmart is allowed to stay open, it is unfair that large gatherings and events are restricted.

“They don't get the overarching concept that we have to eat,” she said.

Noble County did not report a case of COVID-19 until mid-April. When business resumed in the county two months into the pandemic, Ray said the department started to record more cases here and there. Seventy percent of residents work outside the county, and in some cases residents brought the virus home from work. But community spread has yet take hold.

About 45 percent of the county’s cases came from out of the county, normally work-related, and another 35 percent of the county’s cases were secondary infections of family members stemming from the first 45 percent. The other 15 percent of cases have unknown sources, like the Grants’ infections.

The health department is not sure if that handful of cases came from another part of the state or from community spread in the county.

The uncertainty is enough to keep a small percentage of residents, particularly those more at-risk of serious illness, like Rebecca Criswell, 70, living in pretty strict separation.

What Criswell hears about COVID-19 on the nightly news spooks her, she said. She is retired from a career in senior services and lives a quiet life with her cat Daisy, passing the days birdwatching in the backyard for blue jays, cardinals, wrens, and goldfinches. In the evenings, she binges movies on the Hallmark Channel, especially the Christmas films they play on Friday nights at 8:00 p.m.

The biggest adjustment for Criswell has been not being able to visit her 91-year-old mother as much. And she now stocks up on groceries once a week so she does not have to risk exposure from more frequent trips to the Dollar General.

She doesn’t get why other residents will not put on a mask at the store, and it bothers her that there is a get-together in Caldwell every Friday night outside the courthouse, with music and unmasked dancing.

“They even have the big signs at the store that say ‘mandated masks,’ but there’s lots that still don’t wear them. I don’t understand it,” she said. “And you don't dare say anything because you don't know what they'll do.”