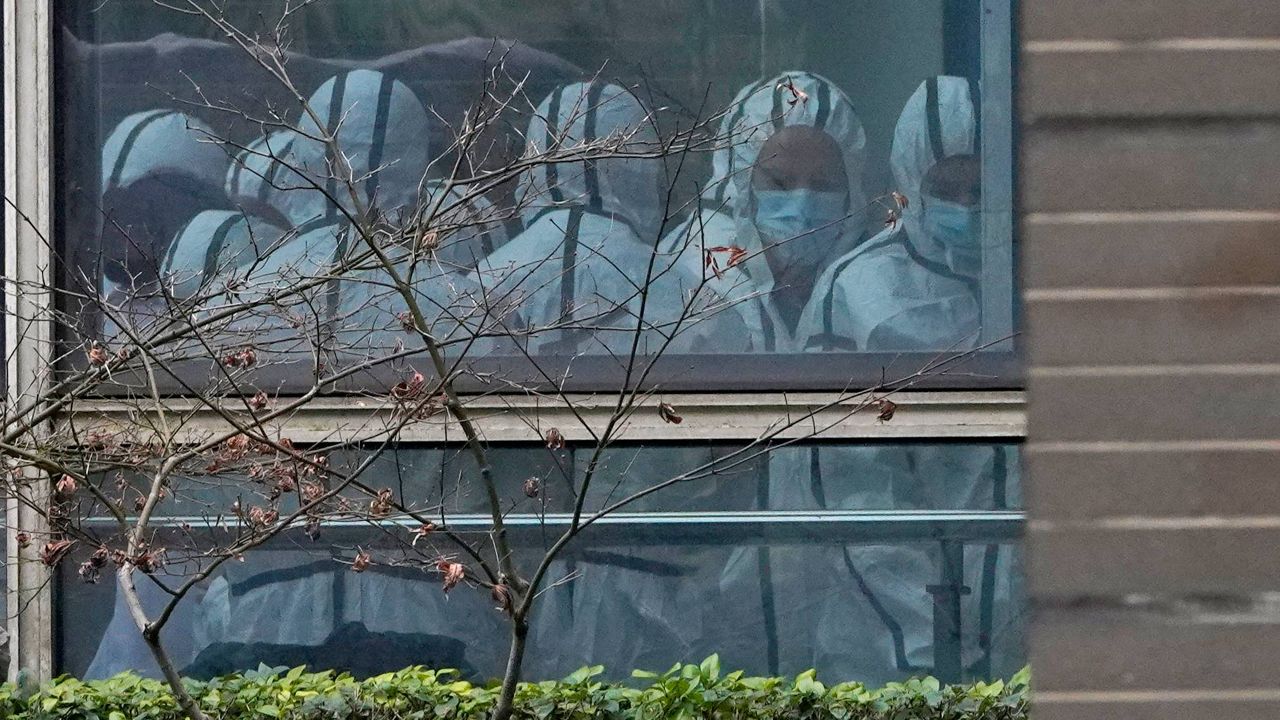

Nearly two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the origin of the virus tormenting the world remains shrouded in mystery.

What You Need To Know

- Nearly two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the origin of the virus tormenting the world remains shrouded in mystery

- Most scientists believe it jumped from bats to humans, either directly or through another animal; others theorize it escaped from a Chinese lab

- Now a growing chorus of scientists is trying to keep the focus on the animal-to-human theory in the hope that what's learned can help humankind fend off new viruses and variants

- But their search for answers is stymied by tensions between the U.S. and China

Most scientists believe it emerged in the wild and jumped from bats to humans, either directly or through another animal. Others theorize it escaped from a Chinese lab.

Now, with the global COVID-19 death toll surpassing 5.2 million on the second anniversary of the earliest human cases, a growing chorus of scientists is trying to keep the focus on what they regard as the more plausible "zoonotic," or animal-to-human, theory, in the hope that what's learned will help humankind fend off new viruses and variants.

"The lab-leak scenario gets a lot of attention, you know, on places like Twitter," but "there's no evidence that this virus was in a lab," said University of Utah scientist Stephen Goldstein, who with 20 others wrote an article in the journal Cell in August laying out evidence for animal origin.

Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona who contributed to the article, had signed a letter with other scientists last spring saying both theories were viable. Since then, he said, his own and others' research has made him even more confident than he had been about the animal hypothesis, which is "just way more supported by the data."

Last month, Worobey published a COVID-19 timeline linking the first known human case to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China, where live animals were sold.

"The lab leak idea is almost certainly a huge distraction that's taking focus away from what actually happened," he said.

Others aren't so sure. Over the summer, a review ordered by President Joe Biden showed that four U.S. intelligence agencies believed with low confidence that the virus was initially transmitted from an animal to a human, and one agency believed with moderate confidence that the first infection was linked to a lab.

Some supporters of the lab-leak hypothesis have theorized that researchers were accidentally exposed because of inadequate safety practices while working with samples from the wild, or perhaps after creating the virus in the laboratory. U.S. intelligence officials have rejected suspicions China developed the virus as a bioweapon.

The continuing search for answers has inflamed tensions between the U.S. and China, which has accused the U.S. of making it the scapegoat for the disaster. Some experts fear the pandemic's origins may never be known.

From bats to people

Scientists said in the Cell paper that SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, is the ninth documented coronavirus to infect humans. All previous ones originated in animals.

That includes the virus that caused the 2003 SARS epidemic, which also has been associated with markets selling live animals in China.

Many researchers believe wild animals were intermediate hosts for SARS-CoV-2, meaning they were infected with a bat coronavirus that then evolved. Scientists have been looking for the exact bat coronavirus involved, and in September identified three viruses in bats in Laos more similar to SARS-CoV-2 than any known viruses.

Worobey suspects raccoon dogs were the intermediate host. The fox-like mammals are susceptible to coronaviruses and were being sold live at the Huanan market, he said.

"The gold-standard piece of evidence for an animal origin" would be an infected animal from there, Goldstein said. "But as far as we know, the market was cleared out."

Earlier this year, a joint report by the World Health Organization and China called the transmission of the virus from bats to humans through another animal the most likely scenario and a lab leak "extremely unlikely."

But that report also sowed doubt by pegging the first known COVID-19 case as an accountant who had no connection to the Huanan market and first showed symptoms on Dec. 8, 2019. Worobey said proponents of the lab-leak theory point to that case in claiming the virus escaped from a Wuhan Institute of Virology facility near where the man lived.

According to Worobey's research, however, the man said in an interview that his Dec. 8 illness was actually a dental problem, and his COVID-19 symptoms began on Dec. 16, a date confirmed in hospital records.

Worobey's analysis identifies an earlier case: a vendor in the Huanan market who came down with COVID-19 on Dec. 11.

Animal threats

Experts worry the same sort of animal-to-human transmission of viruses could spark new pandemics — and worsen this one.

Since COVID-19 emerged, many types of animals have gotten infected, including pet cats, dogs and ferrets; zoo animals such as big cats, otters and non-human primates; farm-raised mink; and white-tailed deer.

Most got the virus from people, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which says that humans can spread it to animals during close contact but that the risk of animals transmitting it to people is low.

Another fear, however, is that animals could unleash new viral variants. Some wonder if the omicron variant began this way.

"Around the world, we might have animals potentially incubating these variants even if we get (COVID-19) under control in humans," said David O'Connor, a virology expert at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "We're probably not going to do a big giraffe immunization program any time soon."

Worobey said he has been looking for genetic fingerprints that might indicate whether omicron was created when the virus jumped from humans to an animal, mutated, and then leaped back to people.

Experts say preventing zoonotic disease will require not only cracking down on illegal wildlife sales but making progress on big global problems that increase risky human-animal contact, such as habitat destruction and climate change.

Failing to fully investigate the animal origin of the virus, scientists said in the Cell paper, "would leave the world vulnerable to future pandemics arising from the same human activities that have repeatedly put us on a collision course with novel viruses."

'Toxic' politics

But further investigation is stymied by superpower politics. Lawrence Gostin of Georgetown University said there has been a "bare-knuckles fight" between China and the United States.

"The politics around the origins investigation has literally poisoned the well of global cooperation," said Gostin, director of the WHO Collaborating Center on National and Global Health Law. "The politics have literally been toxic."

An AP investigation last year found that the Chinese government was strictly controlling all research into COVID-19's origins and promoting fringe theories that the virus could have come from outside the country.

"This is a country that's by instinct very closed, and it was never going to allow unfettered access by foreigners into its territory," Gostin said.

Still, Gostin said there's one positive development that has come out of the investigation.

WHO has formed an advisory group to look into the pandemic's origins. And Gostin said that while he doubts the panel will solve the mystery, "they will have a group of highly qualified scientists ready to be deployed in an instant in the next pandemic."