SUMMERTON, S.C. (AP) — Interior Secretary Deb Haaland joined House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn on Tuesday in visiting a rural South Carolina school that is now part of a National Park Service program to safeguard institutions connected to the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision declaring segregated schools unconstitutional.

Legislation signed by President Joe Biden in May added two South Carolina schools to the Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park. Haaland and Clyburn both spoke about the importance of preserving and learning from America's history.

“These stories are not always easy, and they can be traumatic, but it is my duty to ensure that they are told because our story is America’s story,” Haaland said, standing in a building that once housed Scott's Branch High School, a so-called equalization school for Black students created just miles from Summerton High School, which served only white students. “It’s up to us to tell America’s story.”

The legislation, passed with broad bipartisan support, also designated schools in Delaware, Virginia and the District of Columbia as affiliates of the park, centered in Topeka, Kansas, where the case was based.

Brown v. Board of Education was a ruling for a bundling of cases, including South Carolina’s Briggs v. Elliott, that challenged racial segregation in public schools. In a small park outside Scott's Branch, plaques bear the names of the signatories to the Briggs petition.

“The educational and economic losses from these failed policies are almost impossible to comprehend,” Haaland said. “Sites like the one here in Summerton help us to reflect on the past, to celebrate the progress and allow us to chart a path forward for a more equitable and just future.”

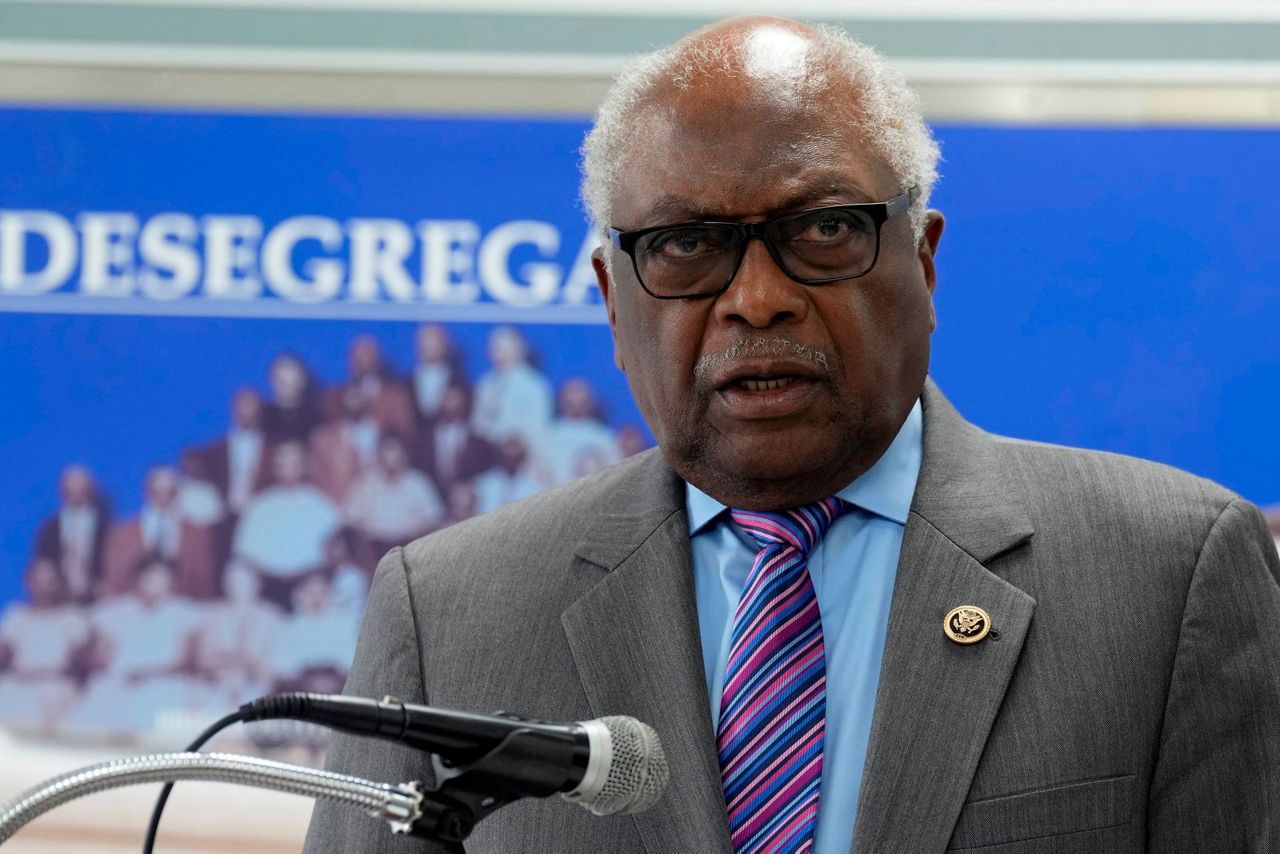

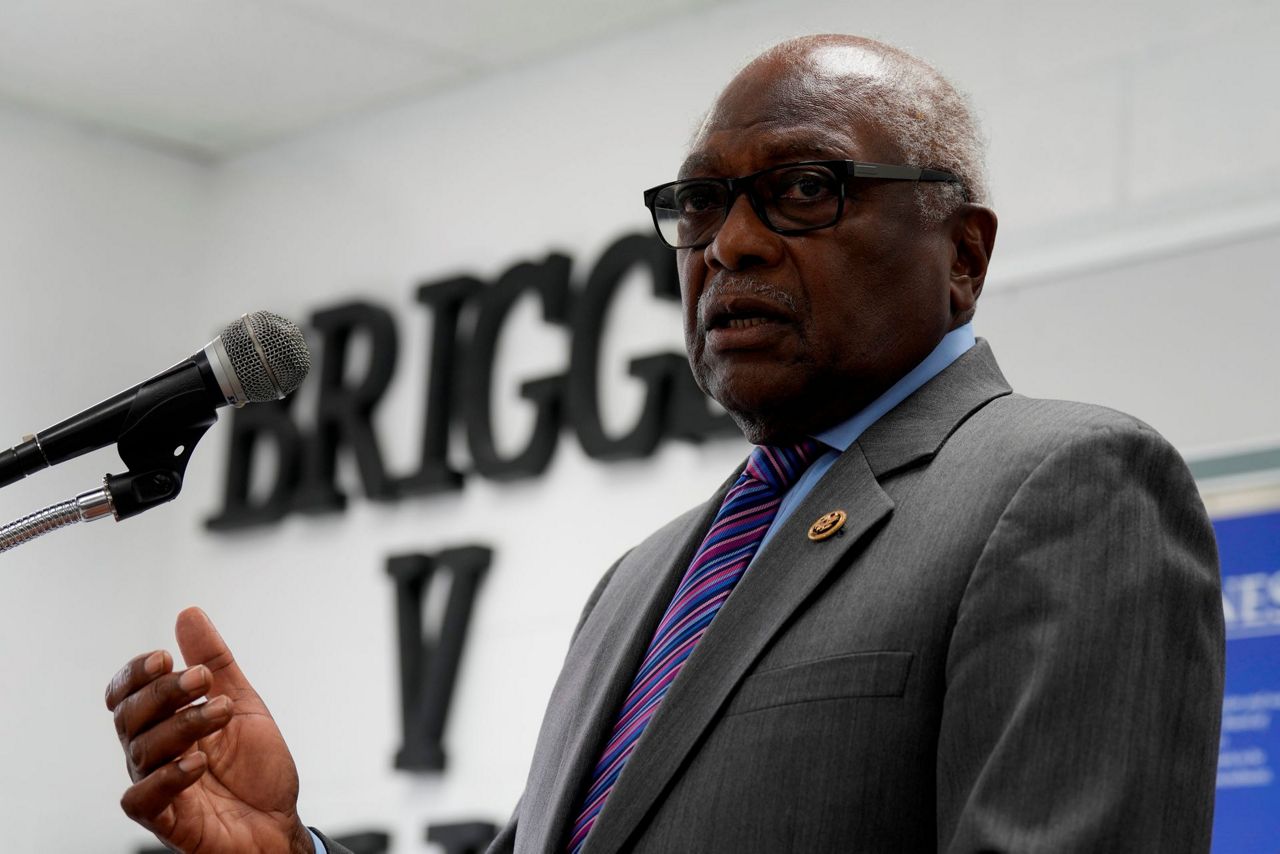

Clyburn, South Carolina's lone congressional Democrat whose 6th District includes the tiny town of Summerton, recalled Tuesday how he learned of the Brown v. Board of Education decision as he walked home from school in nearby Sumter.

“We're here today to make sure that those that come after us learn these lessons of history. You don't learn them by hiding them away or pretending they don't exist," Clyburn said. "That to me, is the ultimate sin, to pretend that they don't exist. These things happen.”

“This is not about sound bites and trying to shame people," he said. "This is about trying to give our history back to our children and our grandchildren.”

Beatrice Brown Rivers was 13 years old when, along with her sister and parents, she signed the petition that led to the Briggs v. Elliott case.

Now 86, Rivers beamed Tuesday as she reflected on the federal recognition for her hometown's place in history, although she acknowledged that many of the same historic struggles over race remain.

“I'm hoping that this will put our little town on the map, and that people will come to see who we are, what we did and how proud we are for all that we have done," River said. “A lot of the same problems that existed back then still exist. Segregation still exists, but that doesn't bother me any more, because I know who I am. ... I know what I need to do, and I go about doing it.”

___

Kinnard can be reached at http://twitter.com/MegKinnardAP

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.