NEW YORK (AP) — Naomi Osaka. Simone Biles. Both are prominent young Black women under the pressure of a global Olympic spotlight that few human beings ever know. Both have faced major career crossroads at the Tokyo Games. Both cited pressure and mental health.

The glare is even hotter for these Black women given that, after years of sacrifice and preparation, they are expected to perform, to be strong, to push through. They must work harder for the recognition and often are judged more harshly than others when they don’t meet the public’s expectations.

So when New York city resident Natelegé Whaley heard that Black women athletes competing in the Tokyo Olympics were asserting their right to take care of their mental health, over the pressure to perform a world away, she took special notice.

“This is powerful,” said Whaley, who is Black. “They are leading the way and changing the way we look at athletes as humans, and also Black women as humans.”

Being a young Black woman — which, in American life, comes with its own built-in pressure to perform — entails much more than meets the eye, according to several Black women and advocates who spoke to The Associated Press.

The Tokyo Games show signs of signaling the end of an era — one in which Black women on the world stage give so much of themselves that they have little to nothing left, said Patrisse Cullors, an activist and author who co-founded the Black Lives Matter movement eight years ago.

“Black women are not going to die (for public acceptance). We’re not going to be martyrs anymore,” said Cullors, who resigned her role as director of a BLM nonprofit foundation in May. “A gold medal is not worth someone losing their minds. I’m listening to Simone and hearing her say, ‘I’m more important than this competition.’”

She added: “Activism and organizing is just one contribution that I’ve given. And we all need to know when enough is enough for us.”

Biles’ message also resonated with Whaley, who co-created an event series in New York City called Brooklyn Recess to preserve the culture of Double Dutch, a rope jumping sport popular in Black communities. Early on, Whaley and co-creator Naima Moore-Turner found they were talking a lot about a mental health component to their events.

“People will say, ‘Let Black women lead, because they know,’” said Whaley, a 32-year-old freelance race and culture writer.

“It’s like, (Black women) know not because we’re some sort of special humans who are supernatural,” she said. “It’s because we live at those intersections where we have no choice but to know.”

ATHLETES AT THE FOREFRONT

The world’s greatest living Olympian, swimmer Michael Phelps, has been credited with elevating a conversation about sports and mental health. But when Phelps hung up his goggles five years ago, he was less likely to be burdened by the chronic health disparities, sexual violence, police brutality and workplace discrimination that Black women, famous or not, endure daily.

Still, the Black women Olympic athletes, echoed by many of their sisters in the U.S. and around the world, stepped forward and said they need to protect their mental health. They didn't ask for sympathy or permission. They demanded people respect their decisions and let them be.

“I say put mental health first because if you don’t, then you’re not going to enjoy your sport and you’re not going to succeed as much as you want to,” Biles, 24, said after pulling out of the women’s team gymnastics final on July 27. Before the Tokyo Games, she was already the most decorated American gymnast in modern times.

Prioritizing mental wellness “shows how strong of a competitor and person that you really are, rather than just battle through it,” she said.

Biles went on to win a bronze medal in the balance beam competition on Tuesday.

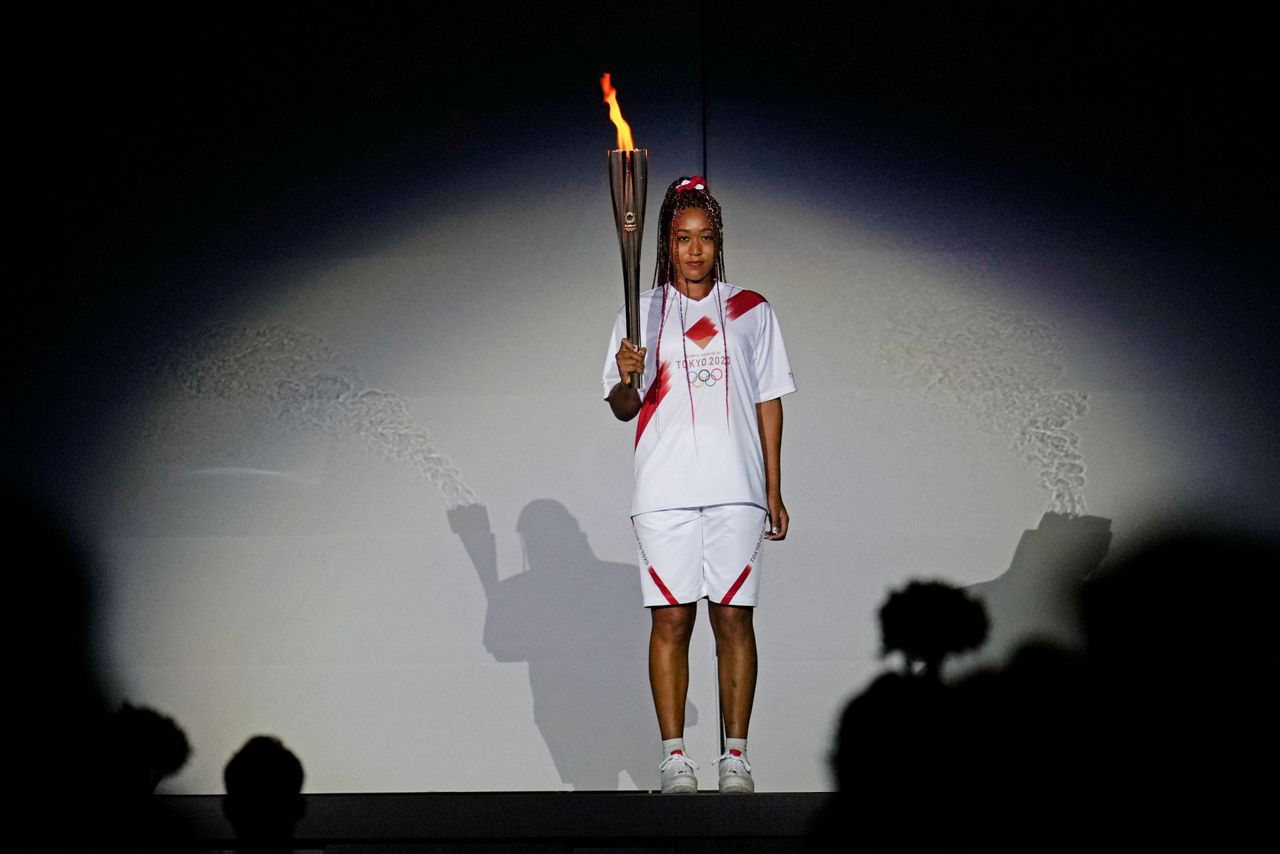

Four-time Grand Slam winner Naomi Osaka, who is of both Japanese and Haitian descent, first raised concerns about her mental health in June when she avoided speaking to the press during the French Open, and ultimately pulled herself out of the competition until the Tokyo Games. Although Osaka, 23, was eliminated from Olympic medal competition, she reiterated her concern for her own well-being.

“I definitely feel like there was a lot of pressure for this,” Osaka said after the Olympic defeat. Weeks earlier, she had written an op-ed for Time magazine in which she said: “It’s OK to not be OK, and it’s OK to talk about it.”

Some of these attitudes might be about age. Many young people feel empowered to speak about mental health in a way previous generations have not.

Biles and Osaka, born months apart in 1997, are members of Gen Z, the first generation whose entire lives have been online. Gen Z-ers are notably more open about mental health struggles, said Nicole O’Hare, a licensed counselor in the Phoenix area.

“It’s so beautiful to witness this sort of normalization of mental health and asking for help,” O’Hare said. “They’re really pushing that barrier and saying I can’t, I need help, I’m struggling, I need support. ... If we really listen to what they’re asking, we can hear a whole lot.”

FACING MORE CHALLENGES

Even with the increased discussion, the overlooking of Black women’s mental and emotional wellness is far from new.

Before slavery's abolition, enslaved Black women rarely enjoyed agency over their bodies or their families. They were wet nurses to enslavers’ wives, objectified for sexual desires and made to toil in fields and homes without credit for successes or innovations. After slavery was abolished in 1865, Black women gained the right to vote with ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, 50 years after Black men.

More recently, Black women’s mental health is likely to be impacted by disparities in health and socioeconomics. African American women have a maternal mortality rate three times higher than white women, and are more likely to report not being believed when they seek treatment for pain from medical professionals.

While they are architects and leaders of the modern movement against police violence, Black women are also victims of it. And with various studies showing Black people as much as three times as likely as white people to be fatally shot by police, Black women are more often grieving the loss of family members or close friends to police violence.

They are also more likely to experience sexual assault in their lifetimes, an issue that likely resonates with Biles, who reported being assaulted by Larry Nassar, the former USA Gymnastics team doctor convicted of criminal sexual conduct with minors. And in the workplace, Black women are paid between 48 to 68 cents for every dollar paid to a white man, according to the National Partnership for Women and Families.

During the U.S. Open last year, following a summer of protests and civil unrest, Osaka had the names of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and other Black Americans killed by police or vigilantes emblazoned on face masks.

But such activism is not a burden for Black women alone, Cullors said, adding that they could simply prioritize themselves if that’s what they consider best.

The message is also resonating beyond well-known figures like Cullors. Liz Dwyer, a Black woman who is a writer and editor in Los Angeles, celebrated Biles on Twitter and declared that “Black women are no longer willing to be the mental health mule.”

“The whole society gets the benefits from the work that we do,” Dwyer said. “And yet the racism and sexism, worrying about the rise of hate crimes, worrying about the safety of your children, worrying about your children being profiled and put in the school to prison pipeline ... that all takes a toll.”

Melanie Campbell, president and CEO of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation and convener of the Black Women’s Roundtable, is of a different generation than Biles and Osaka. She said she has been inspired by their leadership on mental health.

“It motivates me to keep advocating, to keep pushing for civil rights because you see this generation is stepping up,” said Campbell, who was recently arrested while engaging in civil disobedience during a voting rights campaign led by Black women.

“All of us have a role to play," she said. “I can speak about these issues and still be who I am.”

___

Morrison and Hajela reported from New York. Galvan reported from El Paso, Texas. All three writers are members of the AP’s Race and Ethnicity team. More AP Olympics: https://apnews.com/hub/2020-tokyo-olympics and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.