Maine climate change activists say they’re feeling both disappointment and hope for the future after the mixed results of last week’s United Nations summit in Scotland.

World leaders who gathered in Glasgow for the “COP26” conference agreed to offer plans next year to scale up their efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, in a last-ditch effort to keep global warming under the 1.5 degrees Celsius they agreed to in the Paris Climate Accords.

Leaders also agreed to double their funding for climate change adaptation in developing countries and to “phase down,” though not “phase out,” coal use and fossil fuel subsidies.

Johannah Blackman, a co-founder of the Mount Desert Island-based advocacy group A Climate To Thrive, said COP26 felt like watching her kids try to learn to walk.

“Somewhere in their being was the knowledge of what needed to happen, but they just couldn't put it together and they would fall and they’d decide it wasn’t worth it and so they went back to crawling,” she said. “I feel like I saw so many beautiful, powerful, hopeful moments around the conference, but they were all outside of the negotiation halls.”

Blackman said she feels “embarrassment and shame” that countries like the U.S. wouldn’t make stronger commitments to fight climate change on behalf of less wealthy, more at-risk nations, especially those in the global south.

And without more ambitious or detailed efforts from world leaders — such as plans with deadlines, incentives or enforcement mechanisms — she worries even activists in privileged places like Mount Desert Island will face policy and funding limits on the progress they can make toward goals such as energy independence and community-based climate solutions.

“When these agreements fall through, it's once again left to local communities to lead the way, which I'm very proud to say we're doing,” she said. “But it's much, much harder when there's not that kind of prioritization of this work and support at the international level.”

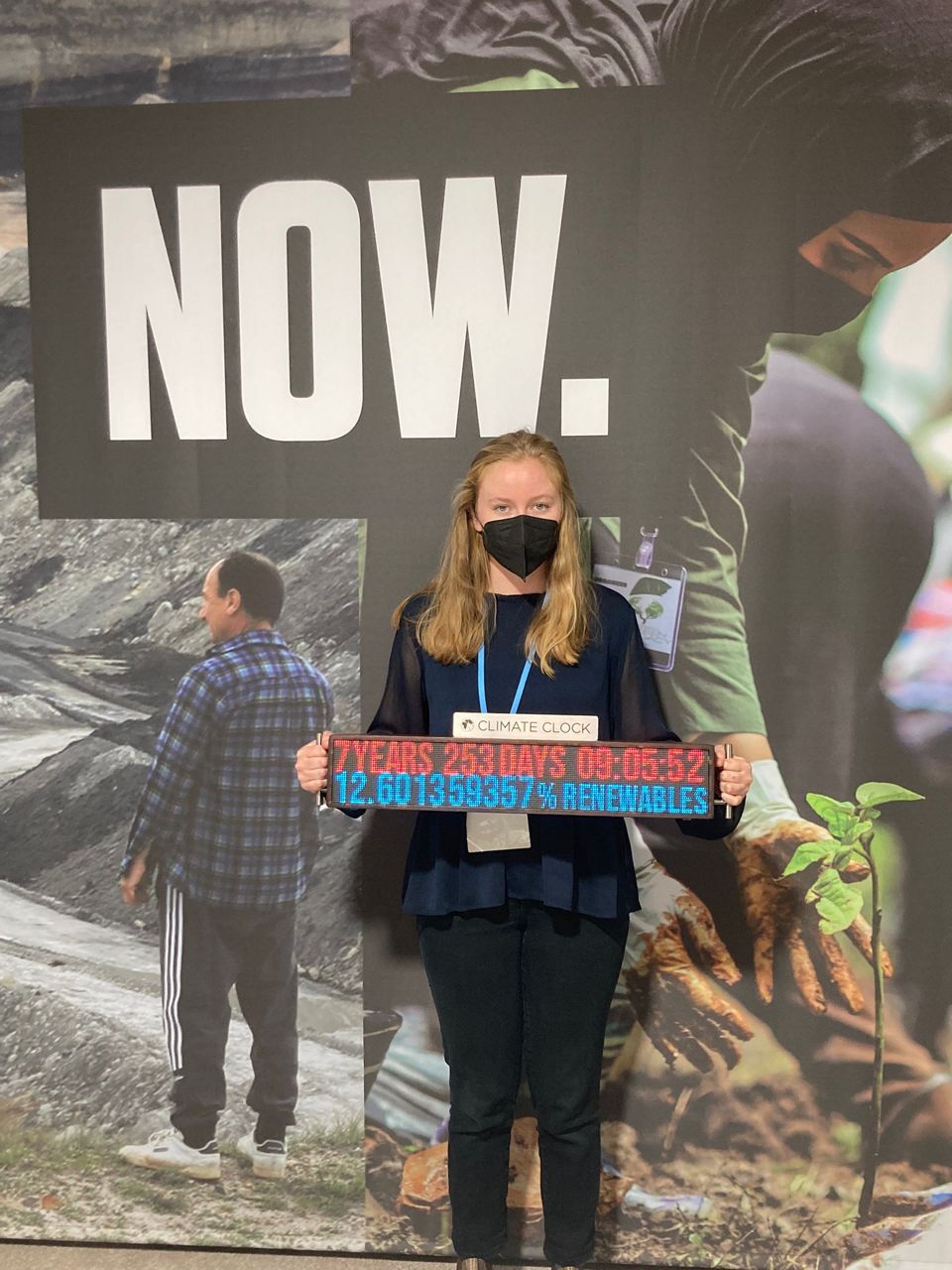

That disappointment was shared by Ania Wright, 24, a recent graduate of the College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor and the grassroots climate organizer for the Sierra Club in Maine.

Wright was in Glasgow for the climate summit last week. It’s the third of these annual U.N. “conference of the parties” or COPs she’s attended. She said she feels less hopeful after this one, which she described as “the Met Gala of climate change,” with famous politicians, fancy styling and formalities making it seem that more was happening than really was.

Still, she said she recognizes that the international action necessary to make faster progress on climate change will have to come from this kind of summit. Wright said she wants to encourage more Mainers to advocate for stronger U.S. action in that setting next time.

“It gives kind of a renewed sense of urgency,” she said, “and also... a recognition that there are folks all over the world that are fighting for the right things.”

Andrew Barton, a biology professor at the University of Maine-Farmington who works with the advocacy collective Maine Climate Action Now, also attended the summit, as a scientist.

He said he saw countless examples of regional and local climate solutions, like the kind that Maine and many of its towns are working on now. It left him optimistic that any eventual agreement will both support and build off those smaller steps, with direct impacts at home.

“I think that reinforced for me how important these more local efforts are, including in Maine… (that) are all going to be percolating up,” he said, “while hopefully we get some policy at the top that's going to provide incentives and rules and other things like that that will drive the key things... especially cutting emissions.”

Dave Reidmiller, who directs the climate center at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, was also hopeful. He said the result of COP26, while perhaps not as ambitious as it could have been, represents real progress and a signal that countries know they can — and must — do more.

He emphasized that these accords have real implications for Mainers. The Gulf of Maine, which his group studies, is warming faster than almost any other part of the world’s oceans, causing ecosystems and species that are key for Maine’s fisheries to change, move around or die off.

Some degree of that change is now unavoidable due to past emissions, Reidmiller said.

“But what we're doing by continuing to ratchet up climate action around the world is to minimize or reduce the risks, right?” he said. “So we have a real vested interest, in the Gulf of Maine, for the outcomes of these talks, because they have very real impacts on the type and abundance of commercially harvested species in the Gulf of Maine.”

A report released during the conference showed that current global emissions goals will blow past the Paris target by a full degree, greatly amplifying the harmful weather effects of climate change and causing more migration and instability.

Reidmiller said that’s why the agreement to return next year with plans to do better is important.

But the impacts of climate change that Maine is already feeling are causing real anxiety for people like 20-year-old Madison Sheppard, who lives in the town of Norway and works with Maine Youth for Climate Justice.

She worries about forest fires in her rural, wooded area — some research suggests wildfires could become a greater risk if climate change fuels short-term droughts. She grew up on Cape Cod, on the ocean, and worries for her family there as sea levels rise.

Her one source of hope from COP26, she said, was the huge turnout and energy at rallies of youth activists that took place around the event.

“This is our future on the line. We’re going to fight for it. We shouldn’t have to be fighting for it, but we are,” Sheppard said. “But at the same time, the people who have the power to make these changes worry me the most.”

CORRECTION: This story was updated Thursday to correct the spelling of Dave Reidmiller's name.