An Iowa professor was the first to use “derecho” to describe a long-lasting, intense wind storm. Exactly 132 years later, the costliest one on record plowed across the same state.

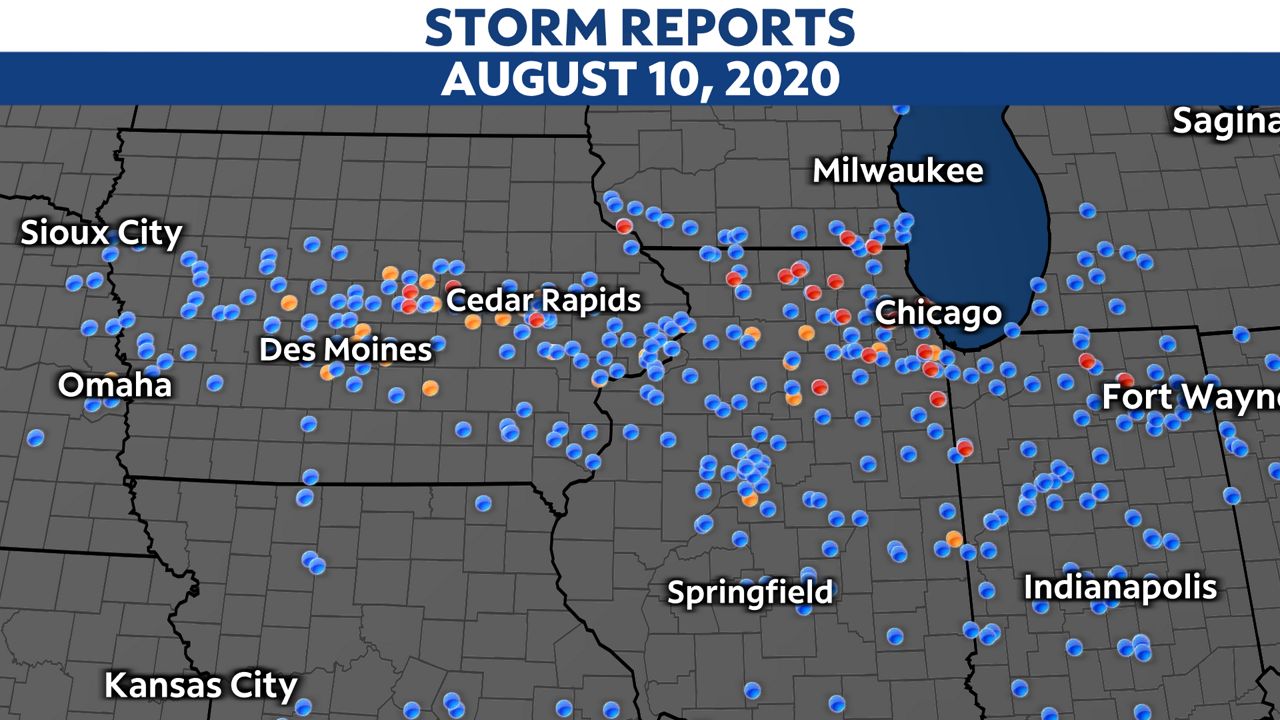

On the early morning of August 10, a batch of thunderstorms near Sioux City, Iowa grew in size and strength as it moved east – not uncommon for late summer. This time, though, it had a huge amount of energy ready and waiting, and it didn’t let it go to waste.

Unfortunately for those in its path, this batch of storms was not well-forecast. The first severe weather outlook of the day put the region in a “marginal” risk of severe weather, the lowest risk category. By the end of the morning, it ramped up to the second-highest risk level and a rare “particularly dangerous situation” severe thunderstorm watch was in place.

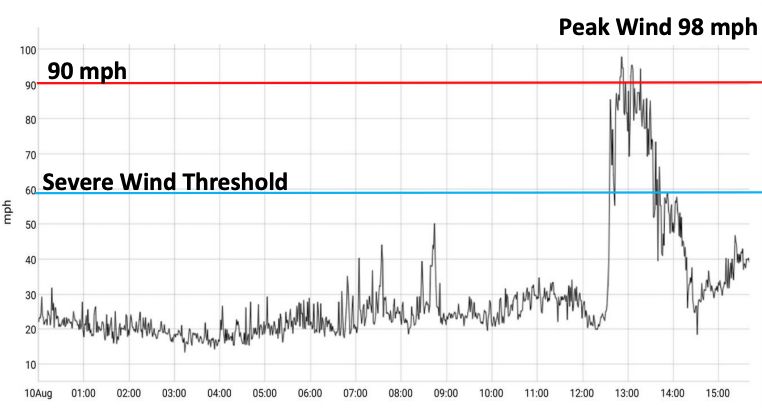

Eastern Nebraska and western Iowa faced damaging winds of 65 to 70 mph mid-morning, and by 11 a.m. it was hitting the Des Moines metro with winds of 75 to 85 mph. Marshalltown, a city northeast of Des Moines, gusted to 99 mph shortly before noon.

The worst was yet to come, though.

The storm hit its peak when it blasted Cedar Rapids during the noon hour. Usually, a line of intense thunderstorms produces strong winds for no more than 10 to 20 minutes. In this case, they lasted for 30 to 60 minutes.

The highest measured wind gust was 126 mph, just west of Cedar Rapids. Damage in parts of the city suggested wind gusts of 130 to 140 mph. Thousands of homes and businesses sustained damage, along with the majority of the trees in the area.

Residents referred to it as an “inland hurricane.” While a derecho is very different from a hurricane, even meteorologists were struck by videos of the wind, saying that the duration and strength reminded them of hurricane landfall videos.

The line of storms raced eastward through the afternoon, producing a swath of winds of at least 80 mph, locally over 100 mph, right into Illinois. It reached the Chicago area by 4 p.m., where winds still gusted over 60 mph. Northeastern Illinois also had 14 tornadoes.

In total, the derecho produced 25 tornadoes in Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Indiana. All were rated EF-1 or lower.

The line of storms finally weakened as it moved past Indiana and southern Michigan the evening of August 10. The fading derecho damaged trees and power lines there, too.

The storms killed four people, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s damage estimate from October puts the cost at $7.5 billion.

Winds crippled utilities. Power outages were extensive because downed trees fell over power lines or the power poles themselves snapped from the extreme wind. Some customers were without power for two weeks, and cell phone networks and internet access were also severely affected.

Millions of acres of corn and soybeans were damaged, along with about 300,000 acres of specialty crops such as strawberries and pumpkins, according to Iowa State Climatologist Dr. Justin Glisan. The damage was so extensive that satellite imagery showed widespread scars. Grain storage also took a hit with the loss of many grain bins.

While the wind outright destroyed many trees, countless others were left standing but damaged. These are vulnerable to disease and decay as well as pest infestations. The loss of animal habitat, runoff control, and overall beauty will take years to replace.

Here’s a look at the fourth-biggest story from 2020: The Easter severe weather outbreak.