We’re celebrating Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month with a look at the fascinating life of Tetsuya Theodore Fujita, a major pioneer in the meteorology world.

Born to two teachers on a small island in Japan, Fujita always wanted to learn, especially when it came to science.

Both of his parents died young, and per the wish of his father, Fujita decided to attend Meiji College on the island where he grew up.

This decision might have saved his life seeing as Hiroshima College was his first choice. Had he attended Hiroshima College, Fujita might have been killed by the first atomic bomb in 1945.

He went on to major in Mechanical Engineering and graduated six months early. After, he taught elementary physics and physics lab, all while living through the horrors of WWII.

Post-war, Fujita applied for a grant for “Weather Science” in 1946, a subject that fascinated him. He went on to research thunderstorms and downdrafts.

He surveyed his first tornado damage in September 1948, which helped develop his love of meteorology.

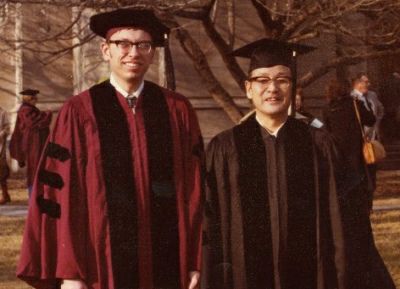

Fujita completed his doctoral degree in 1953 and moved to the United States, where he joined the meteorology department at the University of Chicago.

Funnily enough, he chose the University of Chicago because he had been in constant communication with Dr. Horace Byers, a meteorologist who worked there. While in Japan, a colleague of Fujita found a paper in the trash that Byers wrote and gave it to Fujita. Fujita was so fascinated with the paper, he immediately contacted Byers, sparking their lifelong friendship.

During his early career in Chicago, Fujita studied tornadoes intensely, first exploring the relationship between tornado formation and pressure. His research led to the development of mesoscale meteorology.

After this, Fujita knew the U.S. was the best place to further his studies. After one more trip to Japan in October 1955 to finish a teaching contract, Fujita immediately applied for an immigrant visa and returned to Chicago with his family the following July. He would eventually become a U.S. citizen in 1968.

After returning to the U.S., Fujita studied many tornadoes and tornado outbreaks, conducting aerial surveys and taking countless aerial photographs.

These surveys helped him devise a new tornado severity scale in 1971, the Fujita scale.

Dr. Greg Forbes, who was inspired by Fujita's research to attend graduate school at the University of Chicago, says, "prior to his invention of the Fujita Scale, each tornado was just recorded by its location, path length, and path width, and a description of the types of damage it produced. The Weather Bureau usually assessed this for their Storm Data records based upon newspaper clippings, as few tornadoes were surveyed."

"The Saffir-Simpson Scale had recently been invented to rate hurricanes, and Mrs. Fujita asked Fujita why there was no comparable scale for tornadoes. So, he invented one!"

Meteorologists used this scale for 35 years, and the development of the Fujita scale earned Fujita the very appropriate nickname of “Mr. Tornado.”

In 2007, the Fujita Scale was replaced with the Enhanced Fujita scale, which was created by a team of renowned meteorologists and wind engineers. It takes more details into account, such as building types, structures and trees.

Fujita didn’t stop at his first few discoveries. He kept researching.

After developing the new tornado scale, he went on to study thunderstorms, taking more aerial shots of the tops of thunderstorms by plane.

"For these studies, he had research contracts from NASA and NESDIS, and chartered Lear jet flights from which to take companion movies of the behavior of the storm tops," says Forbes, who participated in this exciting research.

Fujita learned more about the domes of thunderstorms and mapped the temperatures of the cloud features, eventually introducing the basic concepts of thunderstorm architecture.

Forbes also mentions, "Fujita was famous for using tremendously evocative drawings to help explain his research. He would take work home and draft his illustrations overnight. The first thing the next morning we would hear his footsteps coming down the hall after he got out of the rear elevator, and he would almost immediately call me down to his office to show me what he had done and to get my impressions and feedback. He taught us to draft our own drawings, too. How exciting to work side-by-side with a legend!"

Fast forward to when Eastern Flight 66 crashed, supposedly from wind shear during a thunderstorm, Fujita knew he had to investigate. Taking the time history of each flight and logging each pilot’s experience, he discovered microbursts.

This discovery led to the funding of detecting downbursts and microbursts, which Fujita would spend some time in Colorado studying the two.

It wasn’t until 1978 when Fujita would return to studying tornadoes and then eventually hurricanes in the 80s and 90s.

He published many great books on his discoveries, and the University of Chicago named him director of the Wind Research Laboratory in 1988.

In 1989, the university named him the Charles Merriam Distinguished Service Professor.

Researching until he passed away in 1998, Fujita received an outpouring of honors from his peers and even had an award named after him by the National Weather Association.