When Sandy hit, I was the chief meteorologist for New York 1 News. I had been working as a broadcast meteorologist for nearly 20 years, but this was unlike any storm I had ever covered.

Thursday, October 29, 2020 marks the 8th anniversary of Hurricane Sandy. Even today, New York City is feeling Sandy’s lingering impacts.

There are homes on Staten Island that are struggling to deal with a failed city rebuilding program.

The subway system also has delays and repair work that stems from the flooding of subway tunnels by millions of gallons of seawater.

For me, I always pause at this time of year to look back and remember this storm. The loss of 43 New Yorkers still shocks and saddens me. Many of the victims drowned inside their own homes.

A small part of me asks whether I had done all I could to alert people to the coming danger. Deep down, I know that the answer to that question is yes, but it’s still a wound I can feel.

Typically, I enjoy it when storms come our way. I never want to see people get hurt or see homes damaged, but it is exciting to see the power of nature.

Sandy was different.

I was scared and had a feeling of dread in the days and hours before it arrived. The storm was straight out of worst-case storm scenarios that researchers modeled over the past 20 years when doing studies on possible hurricane impacts for New York City.

So many of the catastrophes that scientists had warned would happen did come to pass with Sandy, the flooding of the subway at the Battery and the flooding of airport runways.

I don’t think most New Yorkers know, but our airports are below sea level and protected by a series of dikes.

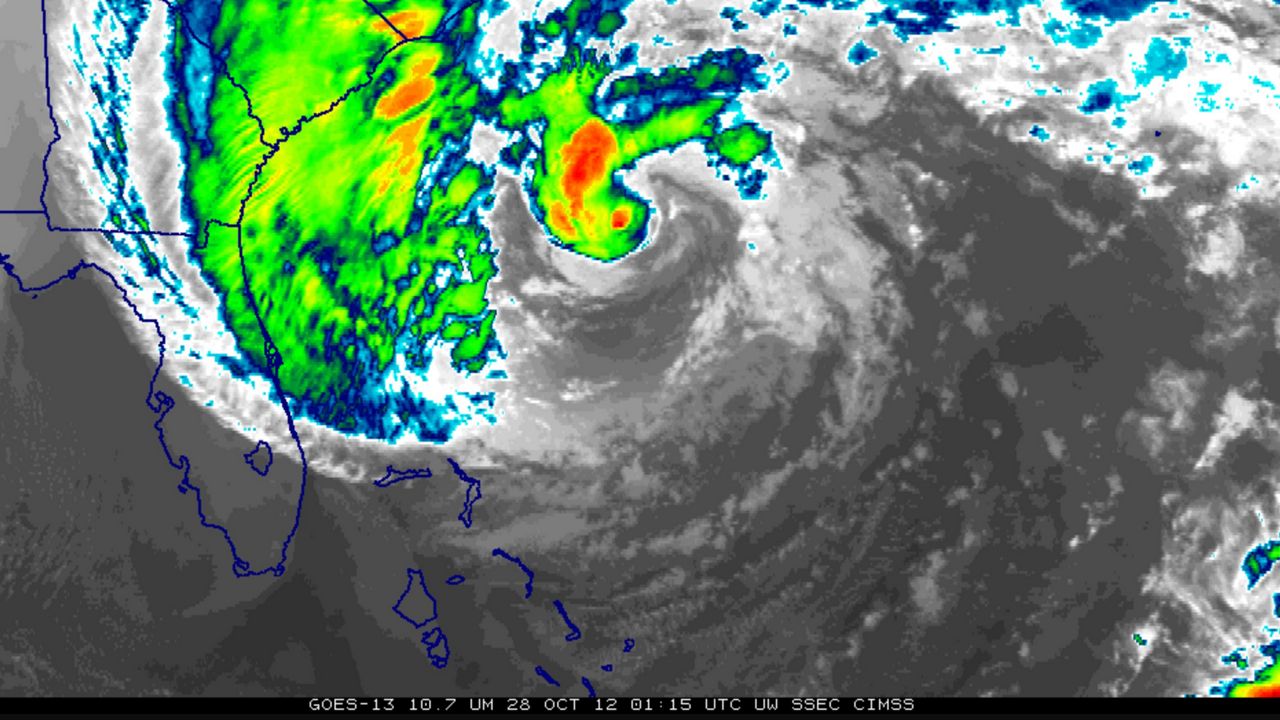

Sandy was the perfect storm. It made landfall during a full moon and high tide, and this maximized its destructive, coastal flooding potential.

The storm surge reached a record of 13 feet. That’s almost one story high.

Waves in the New York harbor measured at an unbelievable 32 feet.

Also, the track of the storm was something that we had never seen. Typically, storms move off to the north and east, but this storm moved east, traveled north, and then made a sharp left turn.

I can still remember seeing the forecast track for Sandy 5 to 7 days before landfall, showing this "left hook."

I dismissed it initially, thinking that this weather model was having a bad day and that the next run of the model would show the storm moving away from NYC. It didn’t, and neither did the next model run.

As the seriousness of the situation settled on me, I recalled all the research papers I had read that had warned about this type of nightmare scenario.

I spent the next few days talking to viewers on tv and Twitter. Twitter was relatively new, and it provided a one on one communication device that was very valuable in preparing for the storm.

I had many users ask personal questions about if they should evacuate and what the storm would be like at their home. When I was off the air, I hovered over the latest forecast data or in meetings trying to express to our planning staff how bad this storm might be.

New York 1 took the storm very seriously. Safety was the priority. The station told reporters to take no chances when out in the field and to seek shelter before things got too serious.

The station bought emergency supplies of food, flashlights, and batteries. We expected to lose power at the station and assumed our crews would be stranded in one location for the duration of the storm.

In the days leading up to Sandy, I got little sleep. The National Hurricane Center issued updates every three hours, and I didn’t want to miss any of them.

On the day of the storm, I packed a bag with clothes and essentials for three days. I gave my home one final check and tried to assure my wife and family that they’d be ok since we live away from the ocean, but they should expect to lose power for a week or more.

I told them I’d check in when I could but that I was going to be live on TV for the duration of the storm. I tried to block them out so that I could focus on Sandy and not worry about them. We had canned food, bottled water, flashlights, extra cash, and a full tank of gas in our car.

When I arrived at the station, I saw the building surrounded by sandbags. We’re about three blocks from the Hudson River and there was the risk that it could reach us during the expected flooding.

The day of the storm, the mood at the station was calm. The city had shut down ahead of it, and until the weather turned, there wasn’t much to report.

I continued to broadcast using phrases and words that I never thought I’d use on TV, “life-threatening storm surge,” “storm like we’ve never seen before,” and “worst storm NYC has ever faced.”

I didn’t want to scare anyone, but I had to use strong language to express the coming danger, especially to those living near the ocean.

During a break, I went up to our roof for some air and to look around. I gazed out to the south and could see NY Harbor, but it looked odd. At first, my brain couldn’t grasp what I was seeing, but eventually, I saw the harbor was a froth of white.

I never saw it look like this before. There were large waves and whitecaps, and the storm wasn’t due to make landfall for about 10 hours.

Right before our noon show, I had some downtime, and I knew this was likely my last break before hours and hours of live coverage. I went for a walk to get lunch at a nearby deli. The usually busy streets were empty, and it was eerie.

On my way back to the station, my phone rang. It was the station. A façade of an apartment building had been sheared off by the wind, and they needed me on camera now.

A lot of the coverage the rest of the afternoon was a blur. I was doing live hits every 10 minutes. In between reports, I tracked the storm and tried to update the information for our viewers and reporters in the field.

The station brought in food, but it was tough to do more than get in a few bites.

I remember a feeling of shock when I saw a report around 4 p.m. on Staten Island by one of our reporters. She was near the beach monitoring the tides and the waves.

Her shot showed hundreds of people who had come to the ocean to see the massive waves and feel the strengthening winds. I wanted to shout at them to go home and get as far away from the water as possible.

The next thing to happen was an alert at the station that a crane was ripped off a building by the winds. It was at this point that I felt fear of the storm. I had to take a minute before going on-camera to settle myself.

As the sun went down and landfall drew closer, I saw our reporter in Coney Island abandon their location as ocean waters rushed in. Meanwhile, in the Rockaway, we saw a video of streets filled with ocean water and cars floating down streets.

The water on some houses reached the 2nd floor. I was worried for the people in these neighborhoods and our crews.

Next, the lights went out. My weather computers and some of the lights in the studio flickered. Our cell phones stopped working too. What happened?

It took some time for us to get the news out, but the city below 34th street was now without power. The ocean rushed into a power station on the lower East Side and caused a blackout.

With no power to the cell towers, most phones were no longer working. Looking out the windows at the station, all you saw was black, wind, and rain.

Having the worst of the storm at night was more chaotic. People couldn’t see downed power wires, and there were sadly several deaths due to electrocution.

We weren’t sure what else could happen at this point. It was late at night, landfall had already happened, and high tide had come and gone.

We were hoping that the worst would soon be over. It wasn’t. We got a bulletin about a fire that had broken out. Breezy Point was on fire.

Seawater had gotten into electrical panels and started fires in homes. The winds from the storm helped spread the fires, and by morning, more than 100 homes had burned to the ground.

Around 3 a.m., the producers came to me and said that I should take a break and get rest. I thanked them but said that I was going to continue. I didn’t feel it was right to leave my city when things were at their worst.

My voice was weak from nearly 24 consecutive hours of broadcasting.

When the sun came up the next day, and the scope of the damage started to emerge, I was able to get some rest as the focus of the story became the damage and not where the storm was going.

I was getting requests from different media outlets across the country and around the world to do interviews. Most of these I did by phone, and I had to do them on the roof of the building because the signal strength of the cell network was so low due to the power outage.

It took days for the power to come back on in the neighborhood where the station was. There was no elevator, so we had to walk up six flights of stairs to get to our offices.

The toilets didn’t work, and we had to pour water into them to get them to flush.

Stoplights were out for more than a mile. You had to be very careful crossing streets as cars were going 40 mph.

Most shops were closed due to the lack of power.

Two days after the landfall, I got back home. My house and family had made it through the storm, and we still had power. There were many tree limbs down nearby, but none at our home.

In the days after Sandy, one of the biggest challenges was getting gasoline. The wind and waves had disrupted the supply chain leaving many gas stations with empty tanks. Also, some gas stations had fuel but no power, so they had no way to pump the gas.

Sandy was a storm like no other. It taught me a lot, and I’m proud of how our station covered the storm and helped our viewers before and after the event.

Despite those successes, I still feel deeply for those that lost lives and homes. It certainly is a storm that I will carry with me forever.

If you find yourself in a weather event where you are to evacuate, please listen. I know that leaving your home is very hard, but you can replace things. You cannont replace a life.