HONOLULU — Orbital missions to the moon previously showed evidence of lunar water, but researchers have now confirmed there is water on the moon with evidence from a spacecraft that landed on the lunar surface.

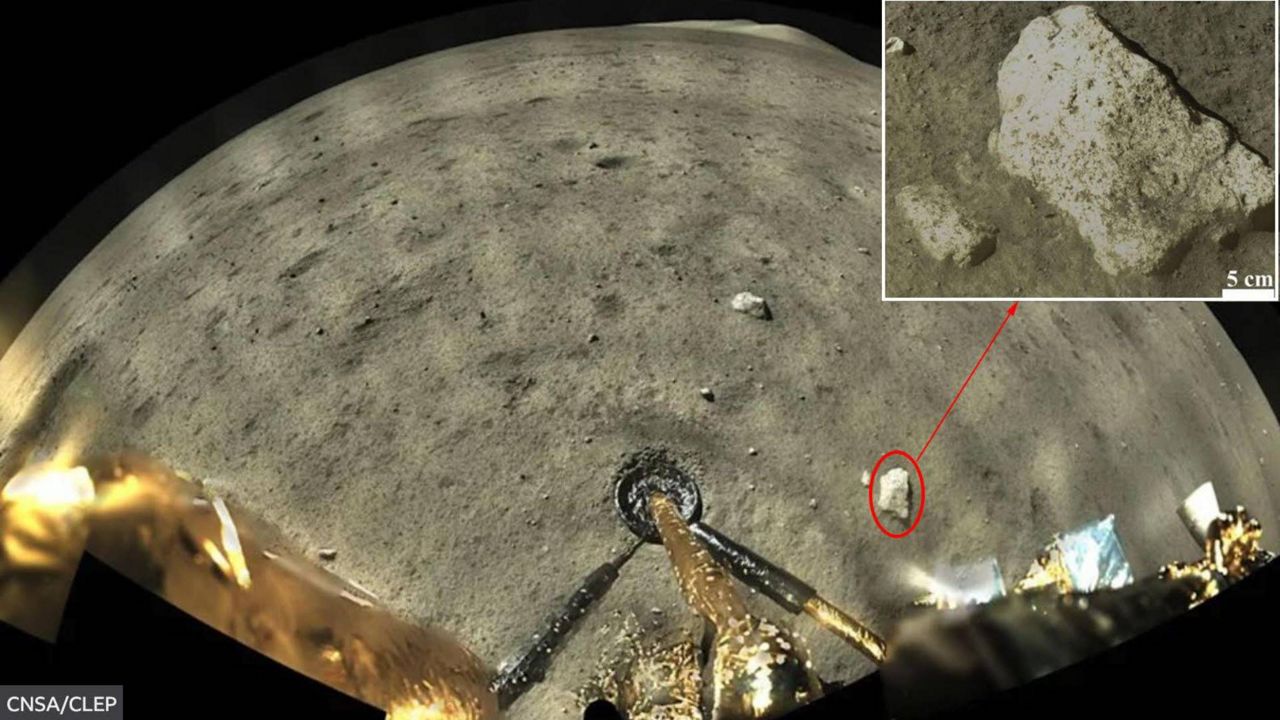

Rock samples were collected from the moon by the Chang’e-5 lander on Dec. 1, and successfully returned to Earth on Dec. 17. The Chang’e-5 is the fifth lunar exploration mission by the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program and the first to bring back samples — the spacecraft is named after the Chinese moon goddess.

This is the first time lunar samples have been collected and returned to Earth since a USSR mission in 1976. The United States first brought back moon samples during the Apollo 11 mission.

Shuai Li, a planetary geologist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, along with Honglei Lin and Rui Xu, who are both scientists at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and others first reported the new water findings in an article published in Science Advances on Jan. 7. Previous research showed evidence of lunar water through sensors that orbit the moon.

The Chang’e-5 collected rock samples and reflectance spectra images from the moon’s mare basalt — a rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava — that is said to be the youngest basalt on the moon. It was likely formed about 2 billion years ago.

To determine that there is water on the moon’s surface, Li and his co-authors examined the reflectance spectra data, which reveals longer wavelengths that humans cannot normally see.

“Pictures normally have three colors,” said Li in an interview Monday with Spectrum News Hawaii. “This kind of data has way more colors.”

One of these longer wavelengths is unique to water, and it was visible in the images analyzed by Li and his co-authors. With this information, the researchers then made replicas of the lunar soil, which gave them an estimate of how much water is in the lunar rocks — typically less than 120 parts per million.

“The soils are very dry,” said Li. “It’s drier than the driest desert on Earth.”

In the future, when humans travel to the moon to establish a lunar base that would utilize water on the moon, the information from Li’s study would be used to determine where to build it.

The findings show that it's too dry in the lower and mid-latitudes for there to be much water; instead, a lunar base built near the shaded polar regions or areas where there were formerly volcanic eruptions would be more successful as they could extract water from the moon.

Li said the results from the study will be cross-validated with research currently being done with the rock samples brought back by Chang’e-5.

Still to be determined, according to Li, is where the water on the moon comes from. It may be from solar wind implementation, which is when solar wind that is largely made up of hydrogen penetrates lunar rocks where oxygen is available and forms water. Or, it may have come to the surface from the lunar interior about 2 billion years ago when there were volcanic eruptions.

“To determine the origins of the water, you have to use isotopes,” Li said. He said other researchers were currently studying this by analyzing the lunar samples brought to Earth.

“We are gathering more and more information from the moon — even though somebody landed on the moon 50 years ago — we still do not know everything about the moon, particularly about the water,” Li said.