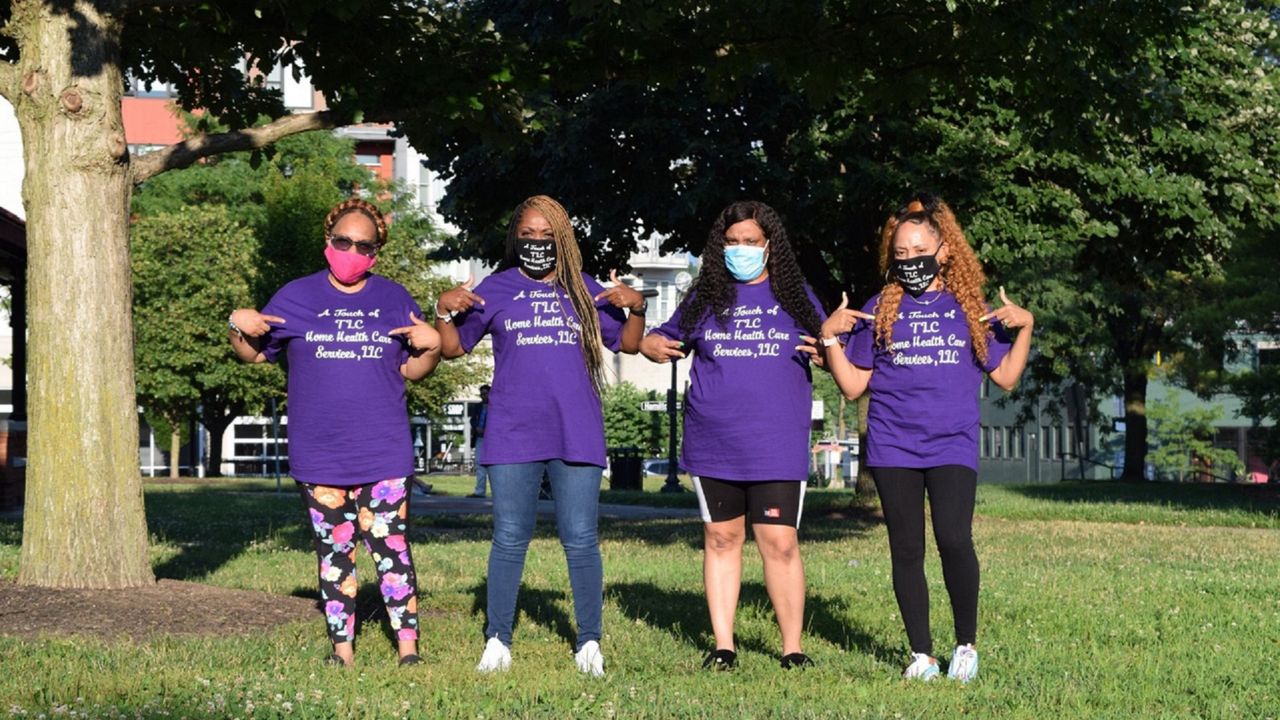

CINCINNATI — Victoria Russell and three of her friends started A Touch of TLC Home Care in 2018. It’s an in-home, non-medical care business that aims to help older adults and others with assisted-living needs remain in their homes.

They had some on-the-job experience, and they’d all taken care of family members in their personal lives. But none of them had any idea how to run a business and didn’t have the confidence to quit their day jobs to start one.

In their first two years of existence, they hadn’t had a single customer.

“We knew what we needed to do, but we didn’t know how to go about it,” said Russell, who works as a title processor for her 9-to-5.

But because of an education program hosted by Co-op Cincy, the upstart business received technical support and mentorship needed to steer them in the right direction.

What You Need To Know

- Co-op Cincy supports worker-owned businesses through educational programming and loans

- The organization is hosting a boot camp to walk teams of prospective business owners through the ins and outs of being a co-op

- The goal of the co-op is to provide workers with more financial stake in the business and more say in how its run

- The program has helped launch more than a dozen worker-owned businesses to date

Starting on March 21, Co-op Cincy is offering a 14-week boot camp to teach teams how to develop and launch a worker-owned business of their own. Participants in Co-op U will develop a business plan and receive hands-on training and mentorship.

They’ll also access seed funding to get them started.

“We’ve really tried to standardize our co-op development process and try to make it as simple and accessible to folks as possible,” said Ellen Vera, Co-op Cincy’s co-director.

Creating more fair investment in local businesses

Founded in 2011, Co-op Cincy is an incubator and network that supports people who want to start worker-owned businesses in greater Cincinnati.

A worker-owned business, or co-op, is a company owned and controlled by its employees. Co-op employees get a share in company profits and they also have a voice in business-related decisions, such as how to scale operations.

“We want to build an economy that’s equitable and inclusive — an economy that works for all,” Vera said.

Russell stressed that quality home care is important work, but she feels it’s underpaid compared to a lot of other industries.

The average home care salary in Ohio is $29,250 per year or $14.06 per hour, according to Talent.com. Entry-level positions start at $24,375 per year.

Because of A Touch of TLC Home Care’s use of the co-op mode, they’ve looking to offer a higher pay rate plus ownership in the business to future employees, Russell said.

The ICA group — a leader in worker ownership in businesses such as home health care — lists on its website that the national caregiver turnover rate is more than 64%. But home care cooperatives average a turnover rate of only 30%.

“We all believe it’s important to push for the most just kind of society and push back on things that are not OK,” Vera added. “It’s important that we proactively create the things that we want to see in the world, in our communities, and that includes the type of businesses.”

Russell admitted to not knowing what a co-op or worker-owned business was a few years ago. But she said the general premise is what she and her friends always had in mind.

“It just made perfect sense for what we were trying to do as a business,” Russell added.

After meeting with the Co-op Cincy team, Russell and her co-owners took part in a separate program called Power in Numbers. It’s a 10-week program for new Black-owned co-ops. All four co-owners are African American.

Russell called Power in Numbers a blessing. They learned the “ins and outs of doing business.”

Right now, A Touch for TLC Home Care is a part-time business. Each of the owners is an equal stakeholder.

“We have one person who is basically our payroll person, but other than that, we all support each other in everything else,” Russell said.

To date, Co-op Cincy has 14 different employee-owned businesses, run by more than 100 workers. Companies range from a residential cleaning service run by Mexican and Guatemalan immigrants to a construction company that does energy efficiency and solar panels.

They also have an urban farm that provides over 200 families with boxes of fresh vegetables every week.

Vera said one of the biggest misconceptions is the prevalence of co-ops across the country. She noted there are more than 1.3 million people in worker-owned business situations in the United States in things ranging from credit unions to rural electric co-ops.

“It’s all these different industries that people use pretty regularly, but people just don’t realize that they’re actually a co-op,” she said. “It’s our job to spread awareness and to let them know that it’s a business governance model that might fit their needs.”

Marie Hopkins, co-owner of Queen City Commons, went through the Co-op Cincy boot camp in 2020. The business partners with local farms and gardens to turn local food scraps into compost.

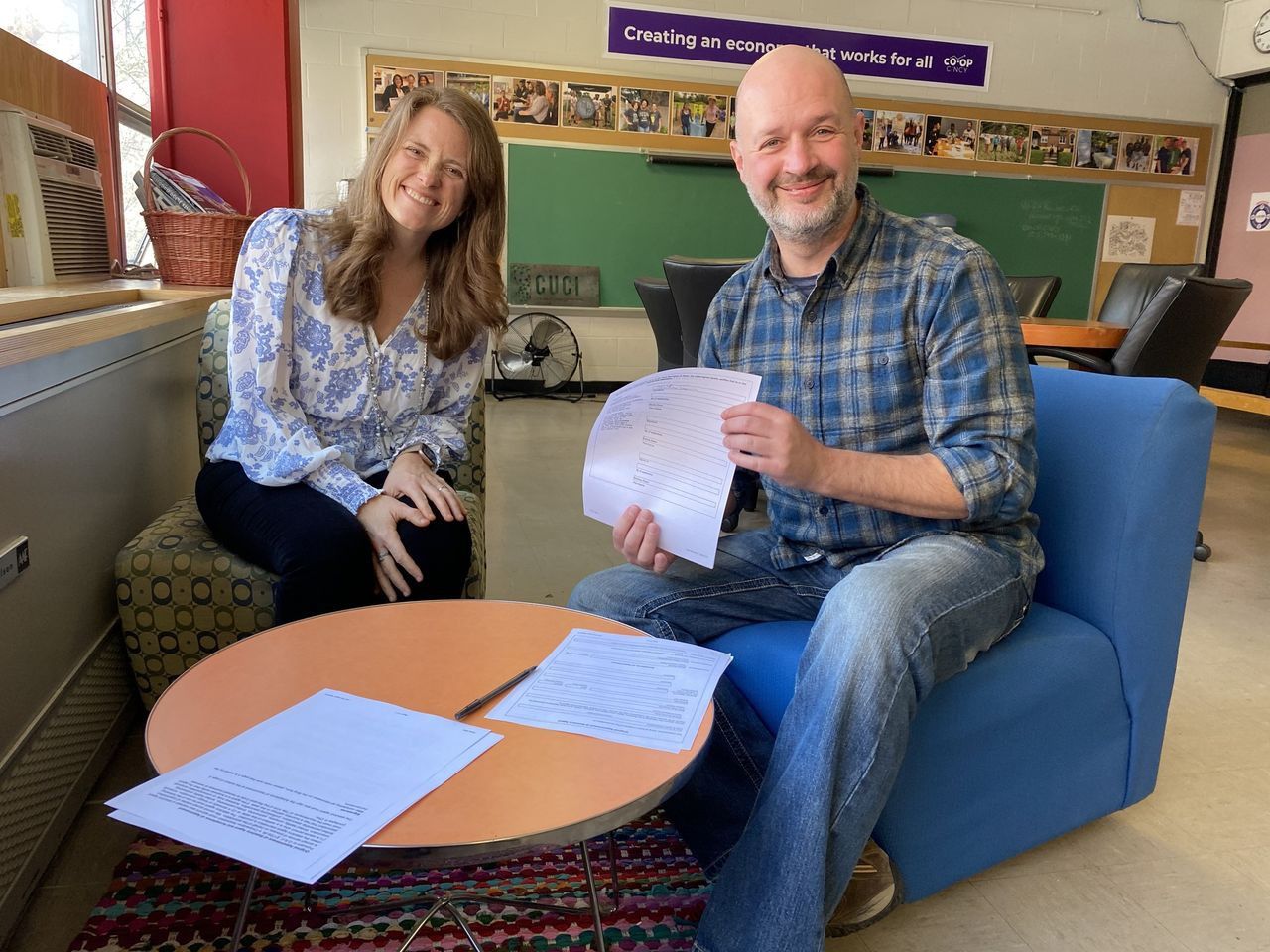

She later brought in Julia Marchese to become a co-owner.

Marchese wanted to be a part of the company, they said, because the work was meaningful and the business model was the “most ethical option.”

“We recognize that in order to get the work done, we need to be treated fairly and equitably and whatnot,” Marchese said.

While they’re not trying to get rich” through Queen City Commons, Marchese voiced a desire to grow it to a point where it can provide better benefits and financial security.

“If I want to have a family one day, that’s going to be necessary, and this seems like a really viable, ethical option to get there,” Marchese said.

Right now, Marchese is working about 25 hours per week. The company is getting ready to bring in a third employee, hoping to expand the company.

Marchese believes that added financial investment may inspire a store commitment from employees.

“It does incentivize wanting to expand the business, not just for the sake of profit, but for having this network of cooperatives and this financial stability,” they added.

Co-Op U open to everyone

The upcoming boot camp is open to teams of at least two people, but teams can also be much larger than that, Vera said.

An “exciting shift” in recent years is Co-op Cincy moving from supporting startups to transitioning traditional businesses to worker ownership, Vera said. Last year, Co-op Cincy helped two businesses move to worker-ownership models: Shine Nurture Center and Heritage Hill.

For the upcoming boot camp, interested teams need to come up with a general business idea. Vera referred to it as doing the general “legwork.”

But once accepted into the program, students will work with the Co-op Cincy team, mentors and other industry experts to go step-by-step through building a nuts-and-bolts business plan and creating a financial model, Vera said.

The cohort meets two hours each week over those three-and-a-half-months. They’ll also have assignments outside of the class that require them to go out in the community and test their business model. Teams will venture into the community to collect feedback from potential clients about what works and what doesn’t.

“It’s really hands-on learning,” Vera said. “We want them to kind of get out there and test their business, versus sitting and writing up a humongous business plan that’s much more theoretical.”

Once they complete the program, participants present their plans to compete for a startup prize. They’ll be first in line for access to Co-op Cincy loan funding.

At the end of its course, A Touch of TLC received a $10,000 grant for having the best business model in the class, she said.

Russell described that money as key to growing the home care business because it allowed them to hire one of their caregiver-owners to work full time on administrative work. It also went toward fees associated with a certification in the state of Ohio to accept clients through Medicaid.

They also received a separate $1,000 startup loan to pay some of the initial bills, including business insurance.

“It’s been amazing — financially, physically, mentally,” Russell said.

Co-op Cincy is part of Seed Commons, a national Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI). It manages the multi-million-dollar pool of loan funds Co-op Cincy raises nationally and locally.

To date, the organization has given about $1.1 million in loans since 2017.

Loan amounts are variable based on the situation, Vera said. But usually, they advise companies to start small and then grow them there.

“Come up with something that we can really test out, and let’s get that kind of financing,” Vera said. “Then come back with what you learned and let’s do another round of loans to help you grow from there.”

While the boot campus program is open to all individuals, Co-op Cincy does focus on trying to work with some of our most historically disadvantaged communities — namely women and minorities, Vera said.

Roughly 66% of the individuals in the network identify as women. More than 60% of the organization’s staff members, including both co-directors, do as well.

But to Vera, she’d like to see the worker-owned governance model in all types of businesses.

“It’s definitely something that we want to see universally,” she added.