UNION, Ky. — When NFL player Damar Hamlin collapsed on the field during a Monday Night Football game, quick response by medical personnel and the application of an automated external defibrillator (AED) were factors that likely helped save his life.

But those aren’t always available to athletes competing at lower levels, like high school sports. Two families in northern Kentucky are trying to change that after living through their own tragedies.

“He was one of the most caring, compassionate, competitive kids you’d ever meet. He always put others before himself. And I know that he would want us to continue doing that in his legacy. And I feel like that’s what we’re doing at this point,” said Kim Mangine, mother of Matthew Mangine Jr. “Matthew didn’t know a stranger. He could meet somebody for the first time and become great friends. Everybody knew him and everybody loved him.”

Processing what happened gets no easier for the Mangine family or the Batson family. Both lost promising young men, who had their whole lives ahead of them, on soccer fields. They both died because of their hearts stopping, in turn breaking the hearts of their family members.

“Matthew passed away of sudden cardiac arrest on June 16, 2020, at soccer practice. Kim was there and witnessed the event. And I didn’t make it until the hospital, a few minutes before the ambulance arrived,” said Matt Mangine.

Mangine Jr., his son, was 16 years old when he died.

Matt and Kim Mangine settled a wrongful death lawsuit with the Diocese of Covington, and St. Elizabeth Healthcare, which employs the athletic trainer at St. Henry District High School, where Matthew attended school.

“There were five AEDs there on campus. And he didn’t get his initial shock until EMS arrived, roughly 12 minutes after his collapse,” Matt Mangine said.

The Mangines say they have become experts on sudden cardiac arrest since their son’s passing. They’ve learned it’s ideal to get an AED on a patient within the first three minutes of their collapse, and that doing so gives the patient a 90% chance of survival.

Every minute thereafter, chances of survival decrease by 10%, Matt Mangine said.

“So simple math tells you he never had a chance. And there was an AED there that, if they could’ve gotten it to him in a timely fashion, that hopefully he’d be sitting here today as a survivor giving his story, instead of Kim and I having to tell his story,” Matt said.

The Mangines started the Matthew Mangine Jr. “One Shot” Foundation to bring awareness to emergency action plans and get more AEDs at sports venues and schools.

They also provide “take 10” training, which they’ve taken from the University of Cincinnati Emergency Medicine. It’s a 10-minute refresher training course on AED and chest compression. They require anyone they donate an AED to take the course, and they’ve trained coaches, athletes and teachers.

“We’re trying to show other people how to be better prepared, so that they don’t have to go through the same pain that we’ve had to go through,” Matt Mangine said.

The Diocese of Covington responded to the settlement with a statement.

“Matt Mangine was a loved and respected student, athlete, and friend at St. Henry District High School. Our school and faith community continues to grieve for him. We admire the efforts of his parents, Matthew Sr. and Kim Mangine, to increase the safety of student athletes throughout Greater Cincinnati through the Matthew Mangine Jr. ‘One Shot’ Foundation. With this legal settlement, it is our hope that the SHDHS community can help support that effort to honor the life of their son, our friend, Matt Mangine.”

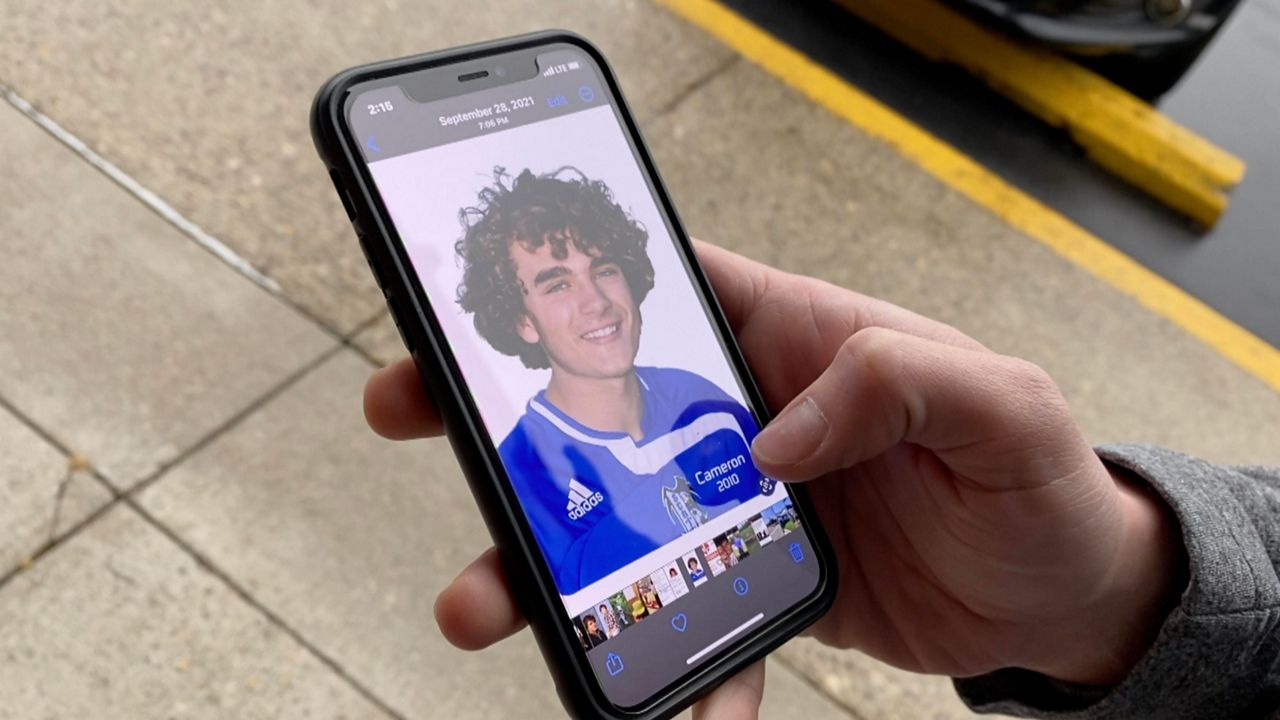

Cameron Batson was 18 years old when he passed away from cardiac arrest during a pickup soccer game in Kenton County in 2010.

Logan Batson, who was 15 years old at the time, was on the field with his brother.

“He was a seemingly perfectly healthy 18-year-old athlete. No history of anything with his heart at all. So for me, when it was initially happening, I thought maybe he was tired or passed out for some other reason. I had no idea that it could be a life-threatening condition at all, until minutes later, people started doing CPR. I was just kind of in shock. Like, why are they doing that right now? I feel like that’s not really needed, but it was,” Batson said. “There was no AED on the field.”

The Batson family has its own foundation, Cameron’s Cause, which has donated over 80 AEDs, and also promoted the importance of emergency action plans.

“Having a plan, and knowing where they’re at, how to use it, and it needs to happen super quickly. I mean, the first few minutes are just absolutely crucial. Because if there’s not an AED on site, and you’re waiting to call the ambulance, how long does it take for them to get there? It could be like 10 minutes, and at that point, it could be too late,” Batson said.

The Batson family would later learn Cameron had a heart ailment, called ARVD (Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia). A few days later, Logan was diagnosed with the same condition.

Logan has an implantable defibrillator inside his chest to detect and treat any life-threatening heart rhythms. His physical activity is limited, and he has had to alter his way of life, but he said he still tries to live every day to the fullest to honor his brother.

“Every day, yeah. I try to do things that would make him happy. I try to also look at my loved ones that are still here and just realize that you don’t want to take any day for granted,” he said. “He was just such a positive figure. He was a role model to me. He was always just smiling and making everyone else smile. He was just a goofball, and his energy was contagious.”

The role AEDs played in saving Hamlin’s life has brought increased awareness to both foundations. The Mangines say they want to use that exposure to continue educating, and to create change.

“Our goal is to get state legislation passed that requires AEDs and EAPs to be followed at all levels of youth sports in Kentucky,” Matt Mangine said.

The stories of these two soccer players were both cut tragically short, but they could save countless lives for years to come.