LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Kentucky’s COVID-19 weekly positivity rate is currently 17.7%. However, that rate doesn’t provide the full picture of COVID-19 in the Commonwealth because it’s calculated using electronically submitted PCR test results.

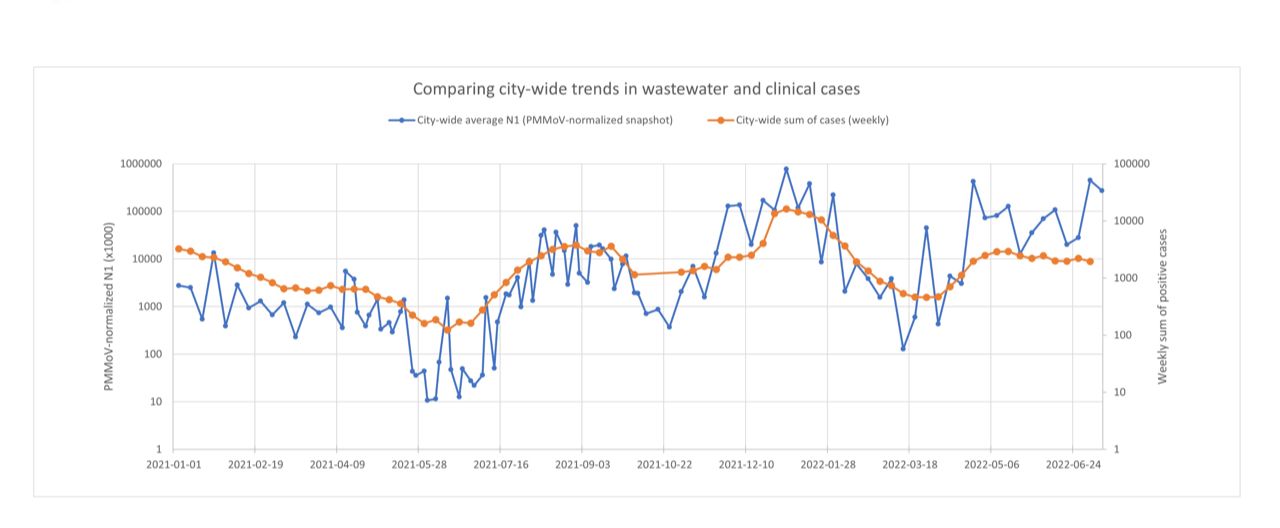

Given people now test with at-home kits and fewer people are testing altogether, there are likely COVID-19 positive cases that don’t get reported. Evidence to back this up can be found in Louisville, where the University of Louisville’s Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute has been testing wastewater for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, since June 2020.

Wastewater has a more accurate picture of COVID-19 cases in a community because, when people have COVID-19, they shed the virus that causes it through stools, even if they are asymptomatic.

What You Need To Know

- There’s a COVID-19 surge in Louisville, according to wastewater testing by UofL’s Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute

- Every week since June 2020, University of Louisville researchers test Louisville’s wastewater for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19

- Wastewater provides a more accurate picture of COVID-19’s prevalence in a community because people shed the virus that causes it, SARS-CoV-2, through stools, even if they are asymptomatic

- Current testing shows the dominant COVID-19 variants in Louisville are BA.4 and BA.5

Ted Smith and a team of researchers at UofL’s Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute are interested in your poop, to put in bluntly.

“Because it provides a source of information about how much infection there is in the community and about which variants of COVID are in our community,” explained Smith, who is director of the Center for Healthy Air, Water and Soil at UofL Envirome Institute and an associate professor of medicine and pharmacology at the university.

Since June 2020, Louisville’s Metropolitan Sewer District (MSD) has collected wastewater samples weekly around Jefferson County for a team of UofL Envirome Institute researchers to analyze and test since SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the infectious disease COVID-19, is shed through stools, even a person is asymptomatic.

“This wastewater work turns out to be, because it’s passive, nobody’s getting tested… it’s just coming through the sewer system, we are able to have a stable reference point about how much infection there is,” Smith said.

Every week, Louisville Metro Department of Public Health and Wellness posts UofL Envirome Institute’s wastewater monitoring reports on its COVID-19 dashboard website.

Currently, Smith said the data shows Jefferson County is in the throes of another COVID-19 surge.

“The amount of virus that’s in the wastewater is on par with the amount of virus we saw in the wastewater in December and January of this past year, and that was the Omicron surge,” Smith said.

“And I think we all remember that that was a pretty serious time, and there was a lot of hospitalization, a lot of people were sick,” he added.

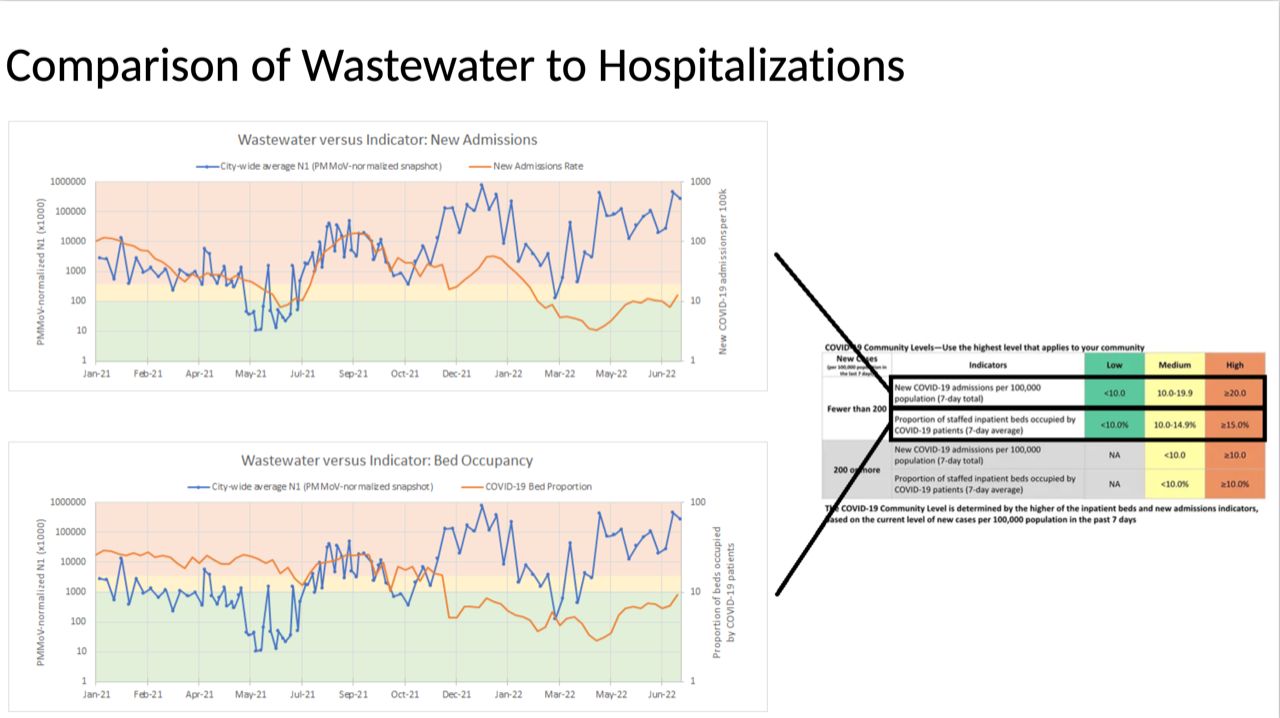

However, the CDC also looks at new COVID-19 hospital admissions and bed occupancy rates by COVID-19 patients to determine if a community’s level of COVID-19 is low, medium or high.

Hospitalization data helps provide a more accurate picture of the effects of COVID-19 on a community because the number of people getting tested has gone down and there is less reporting of positive COVID-19 cases due to at-home testing. Plus, the more people vaccinated against COVID-19 and natural immunity from previous infections translates to fewer hospitalizations, even if someone is positive for COVID-19.

Therefore, UofL researchers also compare wastewater monitoring data to new hospital admissions and beds occupancy rates by COVID-19 patients in Louisville.

“In the past, back in May 2021, we had much lower levels of COVID in the wastewater than we do today, and now we have very high levels, right, very, very high just like at the peak of the Omicron surge, and now we are starting to see the hospital admissions going up,” Smith explained.

The latest SARS-CoV-2 wastewater sampling results compared to hospital beds in Louisville occupied by COVID-19 patients also show an increase on both fronts.

“Which means people are coming to the hospital, and they are staying, and they have COVID,” Smith told Spectrum News.

Sampling and testing the wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 can be an early warning system to help identify areas where COVID-19 may circulate before testing results identify cases.

The data is crucial for helping hospitals anticipate surges because typically as COVID-19 cases go up, so does the number of people admitted to the hospital with COVID-19. It can overwhelm health care systems as shown during the pandemic.

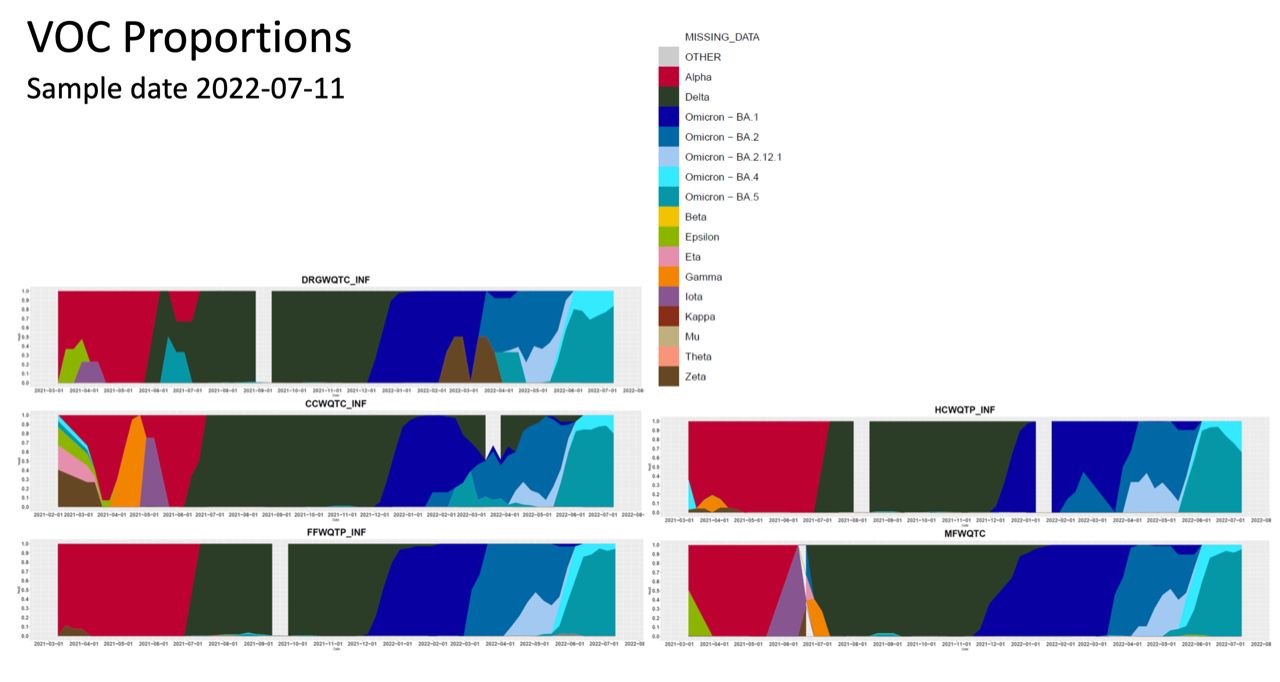

Besides testing the wastewater for SARS-CoV-2, UofL also tests for which strains are present to figure what the dominant variants of COVID-19 are in the community. Currently, wastewater testing shows Omicron BA.5 is the dominant variant in Louisville.

“And a little bit of it is [Omicron] BA.4, but none of it is BA.2, BA.1, Delta, Alpha. We haven’t seen delta for a long time,” Smith said.

According to the CDC, Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 are current variants of concern (VOC) in the U.S. that are being closely monitored. These variants have evidence of an increase in transmissibility, among other characteristics, such as significantly decreased neutralization by antibodies from a previous infection or vaccination.

During an LMDPHW Facebook live on July 11, Louisville’s Interim Director and Chief Health Strategist Dr. Jeff Howard said even though there is some anecdotal, early evidence that shows the BA.5 variant is less susceptible or less prevented by vaccination, vaccination and getting fully vaccinated, including boosters, is the best tool available to prevent COVID-19 and prevent severe illness if it is contracted.

“The bottom line here is that COVID-19 isn’t over. We are going to continue to see variants for the foreseeable future. Folks need to modify their risk,“ Howard said.

“We are still sitting between 66% and 70% of people who are fully vaccinated in the Jefferson County area so we still have some room for improvement, and the best way to prevent this illness, prevent contracting a severe form of COVID is to get vaccinated and boosted. So we are still encouraging people, please get vaccinated,” Howard said.

The reason Smith said UofL does this work is to provide an early warning, which can help public health departments and hospitals prepare ahead of a possible surge or new COVID-19 variant.

“There’s a story in the genetic work that is really important, and so I would just say, at the end of the day, there’s two things we are doing. We’re able to make up for what’s not happening in clinical testing in our community, in terms of understanding how much infection there is,” Smith said.

He added, “And we’re an insurance policy on some novel strain that could escape vaccine, could be very dangerous. We’ll know about it first because of this work that we are doing.”

In addition to testing wastewater for SARS-CoV-2, Smith told Spectrum News that as this research becomes more routine, like monitoring for COVID-19, the hope is Louisville and even Kentucky could use this method of testing for other viruses, such as Monkeypox or Influenza.