FORT WRIGHT, Ky. — A Northern Kentucky man has his life back thanks to the best gift he’s ever received from a former co-worker he barely knew.

Now the two are linked forever.

What You Need To Know

- Mike O’Bryan and Anne Wolking worked together for 10 years, but were never close

- When O’Bryan learned he needed a new kidney, he shared his story on Facebook

- When Wolking saw the post, she felt compelled to donate her kidney to her former coworker

- The two now share a special bond and are as close as family

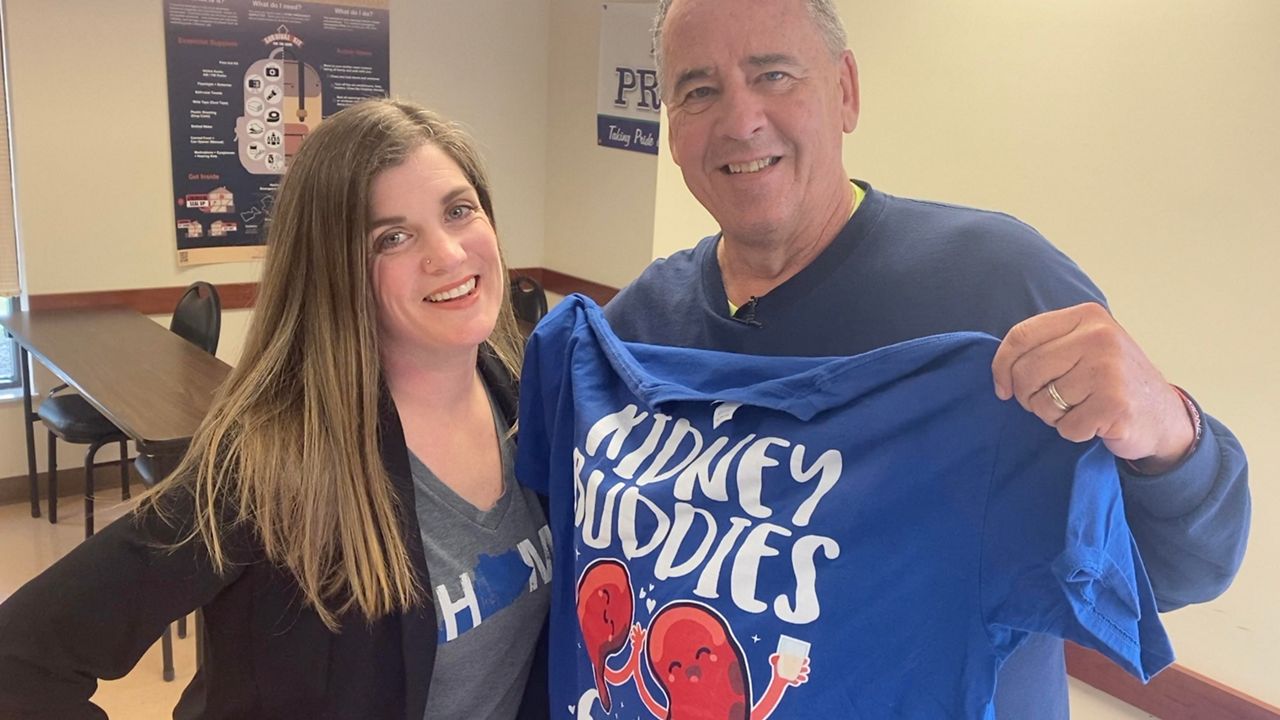

“Best friends” doesn’t begin to describe the bond 55-year-old Mike O’Bryan and 38-year-old Anne Wolking share. Wolking said “big brother and little sister” still doesn’t do it justice.

“Unless you’re in our shoes, it’s hard to explain,” O’Bryan said.

“There’s just not even a word that exists to describe it,” Wolking added.

Maybe it’s “kidney buddies,” but there’s still more to it than that.

For over 10 years O’Bryan and Wolking worked together at Sanitation District No. 1 in Fort Wright, but were never close.

“We worked in the same building,” O’Bryan said, laughing. “Anne would come through every once in a while. That was it. That’s pretty much the extent of it.”

Wolking said they were on “friendly terms” and would only ever exchange “good mornings.”

Both started working at the district in 2006. Wolking had many roles, most recently communications specialist. O’Bryan, who still works at the district, is an engineering inspector.

SD1 is responsible for the collection and treatment of northern Kentucky’s wastewater and also serves as the regional stormwater management agency.

When Wolking left her job in 2017, their relationship was nothing more than Facebook friends. How they went from that to what they are now, they both said, must’ve resulted from divine intervention.

“There is no going back. She’s stuck with me now,” O’Bryan said.

“No, you’re stuck with me,” Wolking said back to O’Bryan, laughing.

An oversimplification of O’Bryan’s job is to help keep the water in the area clean. It’s kind of like how a person’s kidneys’ job is to keep their body clean. O’Bryan has long known there’d come a time that his kidneys no longer being able to do their job could jeopardize his ability to do his.

O’Bryan has polycystic kidney disease (PKD), a highly hereditary disease that took his mother in 2016. His brother and sister both have the disease as well, along with other members of his family. The disease had not caused O’Bryan too much discomfort, just fatigue.

“It was hard during the day to even just stay awake,” he said. “There’s nothing really you can do about it. You just got to watch it.”

In August 2018, O’Bryan learned he was heading toward stage five kidney failure. Normally the size of fists, his kidneys were the size of footballs.

“The week I found out that it really took a dive, I was getting ready to go on vacation, so I kept it to myself when we were on vacation. When we got back, I had more blood work to kind of confirm where it was at. And yeah, it’s definitely a shot in the gut,” O’Bryan said. “It’s finally here, a lot soother than I thought it was going to be. I knew the day was eventually coming, just not then.”

At that point, his options were limited.

Option one was dialysis, something his brother and mother had to resort to. He’d be hooked up to a machine every single night for eight hours. He’d go through two cycles. Each cycle would put fluid inside his body to draw the toxins out, which he compared to sugar on strawberries drawing the moisture out.

“You talk about vacations, doing stuff, going places. I wouldn’t say you couldn’t do it, but it definitely would be a huge undertaking,” O’Bryan said.

Or he could try to find a donor. Option two sounded a lot better. His insurance covered it, but it wouldn’t be easy.

He was given an expected time frame of one to three years. A cadaver kidney would last him about six years, and a living donor kidney, if he could find one, would last him 10 to 15 years.

“There’s so many people out there waiting like I did. But yeah, I got lucky,” he said, glancing over at Wolking.

O’Bryan was referred to both the University of Cincinnati and the University of Kentucky health systems. Being in two separate regions gave him a better opportunity to find a kidney.

In January 2019, he shared his story on Facebook.

“And it was probably the longest post you ever made on Facebook,” Wolking teased.

The post was shared over 100 times.

“People came forward that I never met, that volunteered to go through the process. It’s quite amazing,” O’Bryan said. “You’re honored and blessed that these people would come forward to do something that special for me.”

But donating is not as simple as being willing. Recipients are put through a series of tests, including questionnaires, physicals, echocardiograms, brain scans, a lot of blood work and dental clearance.

On the donor side, many of the same tests are done, as well as cross matching. Doctors don’t want any type of infection during the procedure that could jeopardize the kidney. They also aim to ensure the kidney is an absolute match, and the donor is absolutely sure, not only physically, but mentally and emotionally.

“A lot of people think donation is simply taking a kidney out of one body, and putting it into another body. But there’s so many other puzzle pieces,” Wolking said.

O’Bryan said he thinks seven or eight people applied before Wolking. None of them were matches.

“Obviously, it’s like, shoot,” O’Bryan said. “But I was prepared for the long haul. I really was.”

Meanwhile, Wolking, who currently works as a project management coordinator at PublicSchoolWORKS, said she had felt a calling to donate going back to high school, but until she saw O’Bryan’s post, she never knew when it would be, or to whom.

“And I’ll tell you what, the moment I read your post was the moment that I knew that was exactly it,” she said. “I read that, and it was instantaneous. It was just this… I called it a zap, a gut punch. Just this warm feeling draped over me, that I knew this was it. This was the moment that I had been waiting for, the ‘yes’ that I had been waiting for.”

At first, Wolking thought she’d play the timing game. Her husband, Doug, was changing jobs. And she saw the response O’Bryan was getting from others.

“And so I thought, well, maybe I misjudged. Maybe I just got excited for Mike. Maybe I just wanted him to get the kidney,” she said. “And then he’d make those updates. And just say, ‘unfortunately, this one fell through, or that one fell through.’”

One day, she was sitting in church with her husband.

“After church I looked at him, and I said, this is not about my timing. And it is not about your timing. It is God’s timing. And I am very much being called to proceed in the process of seeing if I’m a donor. And that was that,” Wolking said.

But there was one more hurdle to clear: her three children.

“In the back of my mind, I thought if my children at all said no, then as a parent, it’s going to be, we’re going to stop it right now,” she said.

She laid out the case to them. The response from her son Deacon, who was 11 at the time, sealed the deal.

“‘So Mike is sick, his body is not working, and he needs a kidney?’ And I said yes. And he said, ‘and you have two kidneys, but you only need one kidney?’ And I said yes. And he said, ‘and you are going to be fine, and you will live a long life?’ And I said yes, that is the plan. And he said, ‘Well, obviously the answer is yes.’ And that was it,” Wolking said. “If I was already 100% sure, I was 127,000% sure by that point.”

In May 2019, she put herself on the list.

Doctors told her there was a significant chance for a successful transplant, and a normal, healthy life after. But with things like these, there’s always risk.

“Put yourself there at worst-case scenario with your recipient. What happens if there’s rejection? What happens if the unmentionable happens? How would you manage that? How would you handle that? And to face your mortality, and it’s right there, is eye opening. It kind of gives you a greater appreciation for life,” Wolking said.

A few months later, on August 9, 2019, O’Bryan was thinking option one, dialysis, was his only option left.

“I met with a surgeon on that Friday, scheduled the surgery to have ports put in to be able to start dialysis,” he said.

The following Monday, though, Wolking found out she was a match. On Tuesday, O’Bryan found he had a donor, but he didn’t know who yet.

On Thursday, a day before he was scheduled to go through with option one, an old co-worker surprised him with option two. O’Bryan did not know Wolking had applied.

Another SD1 employee recorded Wolking sharing the news with O’Bryan. They watched the video together, both crying.

“I was literally speechless. I didn’t know what to say,” O’Bryan said.

“It’s awesome. It’s a combination of a lot of work. And probably a lot of prayer on both of our sides,” Wolking added.

Their schedules, combined with a new job for Wolking’s husband, meant time slots for the surgery that worked for both of them were few.

“Not even a month after he found out he was getting my kidney, we were on the table,” Wolking said laughing. “It was 90% excitement, and 10% nerves. And then it started shifting from like 80% excitement to 20% nerves.”

On September 9, 2019, surgery went smoothly. Wolking’s surgery lasted an hour to an hour and a half. The hand-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy made two small incisions on the upper part of her abdomen, and a bikini line incision on the lower part of her abdomen.

“And then the doctor took his hand, grabbed the kidney, and then guided it through the incision, and there it was, and placed it in an ice bath, and took it directly over to Mike, where then they started his procedure,” Wolking said.

O’Bryan’s surgery lasted two to three hours. One of Wolking’s kidneys was now inside of him and started functioning right away. Wolking went to go see him in the ICU the next day, but first was embraced by O’Bryan’s then 26-year-old son, Tyler.

“And he just said, ‘thanks for saving my best friend,’ and completely lost it. And I lost it,” Wolking said. “I knew what I was doing when I donated my kidney. I knew that I was granting this man a lot of ordinary moments, and big moments, and holidays and birthdays. But the fact that I was able to give a son more tee times with his dad, more football games, more grill outs, phone calls, I would want the same. That will stay with me for the rest of my life, that moment.”

Now, two and half years later, O’Bryan’s fatigue is mostly gone, and his kidney function numbers are “great.”

“I like to rub it in, because sometimes they’re a little better than hers,” he said, laughing.

He also likes to check in with her donor.

Wolking goes to the gym four to five times a week. She’s training for the Flying Pig Marathon 5K. And many days, she said, she forgets she only has one kidney.

O’Bryan gets to experience those tee times, football games and grill outs with his son.

“Cherish every day,” he said.

The two of them are closer than they ever were working in the same building.

“Our friendship is one thing. But it’s family now. Her family, my family,” O’Bryan said.

“I have no doubt in my mind that you’ll be at my kids’ high school graduation, and all of the family events that we have. They’re in. They’re lifers,” Wolking said, looking at O’Bryan.

They again tried to describe the bond.

“It’s hard. It’s really hard. You know? It takes a really special person to do something like that,” O’Bryan said crying. “I got one.”

“It was easy,” Wolking responded.

April is National Donate Life Month. For more information about organ donation, visit https://www.donatelife.net/ndlm.