CLEVELAND — A recent study led by the Cleveland Clinic identified that sildenafil, an FDA-approved drug used to treat erectile dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension, reduced the risk of Alzheimer's disease by nearly 70% – signaling that the drug could be a potential treatment or preventative measure against the ailment.

Researchers behind the study, published in Nature Aging, used computational methodology to screen and validate FDA-approved drugs as potential therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. The team created a large-scale database of more than 7 million patients, comparing sildenafil users to non-users.

The drug sildenafil is commonly known as the brands Viagra and Revatio.

The data shows sildenafil users were 69% less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than non-sildenafil users after six years of follow-up.

Scientists indicated that there would be a need for follow-up clinical testing of the drug's efficacy on Alzheimer's patients.

“This paper is an example of a growing area of research in precision medicine where big data is key to connecting the dots between existing drugs and a complex disease like Alzheimer’s,” said Dr. Jean Yuan, the program director of Translational Bioinformatics and Drug Development at the National Institute on Aging. “This is one of many efforts we are supporting to find existing drugs or available safe compounds for other conditions that would be good candidates for Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials.”

Dr. Feixiong Cheng of Cleveland Clinic’s Genomic Medicine Institute, who led the study, and his team launched the study to better understand subtypes (endophenotypes) of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease to reveal common underlying mechanisms, with the hope of repurposing drugs that could make an impact.

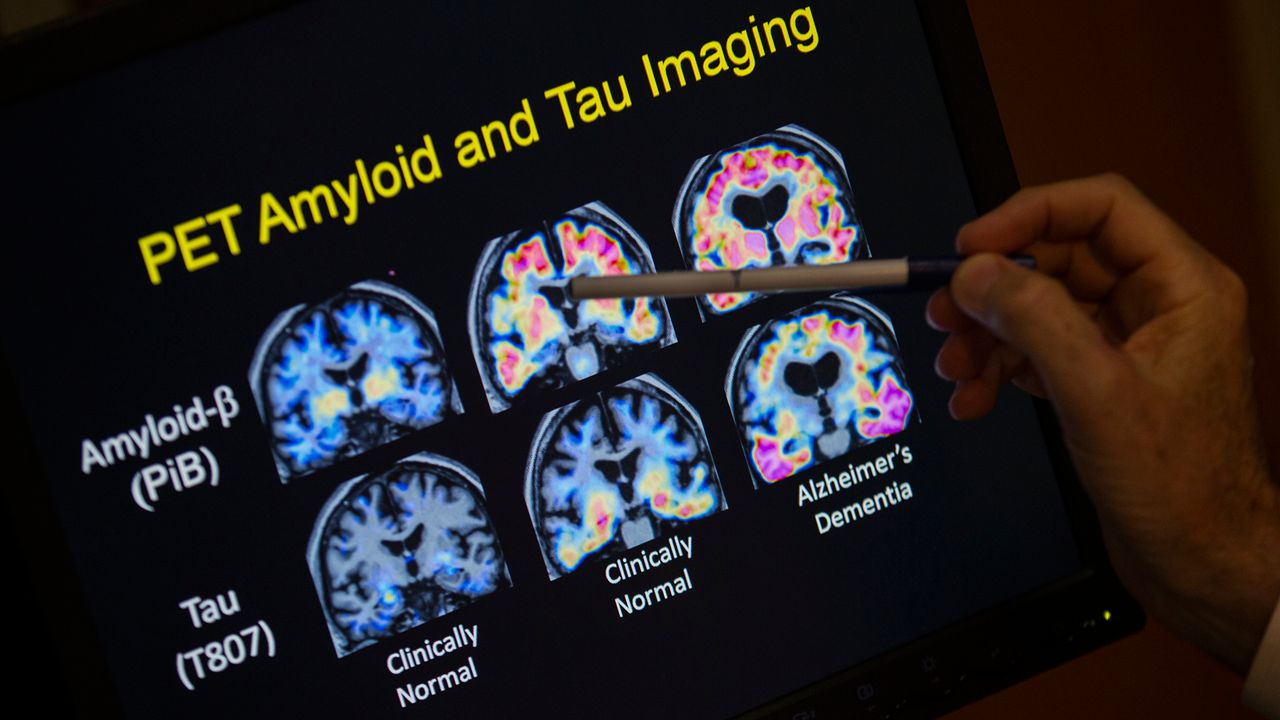

Two trademarks of Alzheimer's disease is the buildup of beta amyloid and tau proteins in the brain, which leads to amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles. While the location and the amount of these two proteins may help identify the subtypes to better understand the disease, there's currently no FDA-approved anti-amyloid or anti-tau small molecule Alzheimer’s treatments on the market

“Recent studies show that the interplay between amyloid and tau is a greater contributor to Alzheimer’s than either by itself,” said Cheng. “Therefore, we hypothesized that drugs targeting the molecular network intersection of amyloid and tau endophenotypes should have the greatest potential for success.”

The team used a large-scale gene mapping network that integrated genetic and biological data to see if one of over 1,600 FDA-approved drugs could be affective against Alzheimer's. Drugs that pinpointed both amyloid and tau proteins had a much greater effect. Sildenafil had a 55% reduced risk of the disease compared to losartan, 63% compared to metformin, 65% compared to diltiazem and 64% compared to glimepiride.

“Sildenafil, which has been shown to significantly improve cognition and memory in preclinical models, presented as the best drug candidate,” said Cheng.

Once the team saw the data, they decided to further study sildenafil's impact by developing an Alzheimer’s patient-derived brain cell model using stem cells. From that model, they found that sildenfil increased brain cell growth and decreased hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins — which is to blame for the loss of normal physiological function.

“Because our findings only establish an association between sildenafil use and reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease, we are now planning a mechanistic trial and a phase II randomized clinical trial to test causality and confirm sildenafil’s clinical benefits for Alzheimer’s patients,” said Cheng. “We also foresee our approach being applied to other neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, to accelerate the drug discovery process.”

The latest development in treatments for Alzheimer's came over the summer. In June, the FDA gave conditional approved the drug Aduhelm (aducanumab), the first new medication to treat patients with Alzheimer’s disease in nearly two decades. But about a month after it was approved, U.S. health regulators signed off on new prescribing instructions that are likely to limit its use.

The new drug label emphasized that Aduhelm is appropriate for patients with mild or early-stage Alzheimer's but has not been studied in patients with more advanced disease. This caused confusion and hesitation from physicians nationwide, and many places like the Cleveland Clinic came out and said it would not be administering the drug until it has been studied further.

In June, the health news site Stat reported several new revelations about the unusually close collaboration between Aduhelm drugmaker Biogen and FDA's drug review staff. In particular, the site reported an undocumented meeting in May 2019 between a top Biogen executive and the FDA's lead reviewer for Alzheimer's drugs.

The meeting came after Biogen stopped two studies because the drug seemed didn't seem to slow the disease as intended. Biogen and the FDA began reanalyzing the data together, concluding the drug may actually work. The collaboration ultimately led to the drug's conditional approval two years later, on the basis that the drug reduced a buildup of sticky plaque in the brain that is thought to play a role in Alzheimer’s disease.

FDA interactions with drug industry staff are strictly controlled and almost always carefully documented. It's unclear if the May 2019 meeting violated agency rules.

The drug is still on the market and is intended to treat the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. On top of the hesitation from physicians, the other issue is that there's hesitation from insurance companies. Medicare won't decide whether to pay for Aduhelm until next year and many other insurers appear to be waiting for the government to make its decision before they make their own.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.