LOUISVILLE, KY. — On Feb. 8, when Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear released the first statewide breakdown of COVID-19 vaccinations by race, it showed Black Kentuckians had received just 4.3% of total vaccines.

“That’s not acceptable,” Beshear said at the time. “It needs to be closer at least to 8%, which is the makeup of the population.” According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Kentucky is 8.5% Black.

On each subsequent Monday, Beshear has updated the demographic numbers, outlined the challenges to increasing vaccinations among Black Kentuckians, and detailed the efforts the state is making to overcome them. But five weeks later, Black Kentuckians make up only 4.81% of those vaccinated in the state. That’s an increase of just over half a percentage point.

“Any sort of forward movement is a good thing, but I would not classify that as good progress,” said Pastor Timothy Findley of Kingdom Fellowship Church in downtown Louisville.

The uptick in vaccinations among Black Kentuckians has been slight, but steady since the start of February, increasing each week by an average of one-tenth of a percent.

On Feb. 22, Beshear was “not satisfied” with that progress. On March 1, he said it was “not nearly enough.” On March 8, there was “a long way to go.” And on March 15, he said the numbers were “not OK.”

For weeks, Beshear has detailed some of the reasons Black Kentuckians have received a disproportionately small share of vaccinations. The problems, he has said, relate to vaccine accessibility, the underrepresentation of Black people in groups that were vaccinated early, especially healthcare workers and educators, and hesitancy to get vaccinated among some Black people.

“We’re trying to partner with everyone to address understandable hesitancy based on historical, not only inequities, but wrongs,” he said on Feb. 15.

To that end, the state has worked with Black churches, vaccinated faith leaders at the Capitol, and partnered with the NAACP. The state is also working with hospitals in Louisville and Lexington to bring vaccines to people of color in and around their neighborhoods via pop-up clinics.

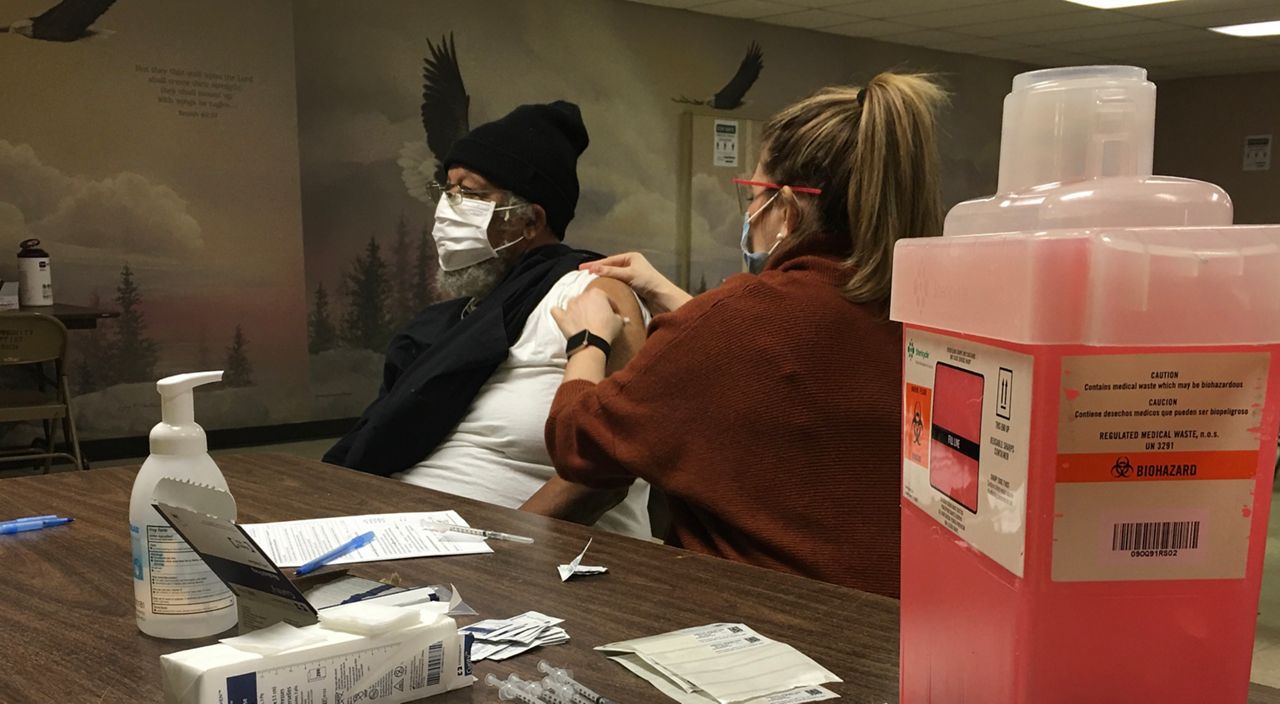

Last February, Findley's church hosted a pop-up vaccine clinic. With the help of UofL Health, nearly 1,000 people were vaccinated. Many of them lacked easy access to a vaccination site or the technology needed to sign up for a shot.

Findley said these problems could have been anticipated if people, like himself, were involved in the vaccine rollout plan from the beginning.

“If we would have brought Black leaders to the planning table in the late part of 2020, I believe that things would be different now,” he said. “Trying to bring us in late-January, early-February was a critical, critical mistake."

Crystal Staley, a spokesperson for Gov. Beshear said, the administration did, in fact, start this effort in 2020.

"To prioritize health equity and address hesitancy in our vaccine distribution process the administration started working with nearly 60 community leaders across the commonwealth who represented Black, Latinx and rural communities beginning last year," she said. "Through this work, our vaccine team has implemented communication strategies to amplify trusted voices through communities and are partnering with many medical providers to conduct community vaccine events."

Another problem Findley has with the rollout effort is that it did not reflect the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on Black people. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Blacks are 2.8-times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 as whites, and 1.9-times more likely to die.

Findley said that rather than including only those 70 and older in the first phase of vaccines, for “Black and Brown people, that number should have come down to 55 and included those with preexisting conditions.”

“That's what equity is. It's not about equality in this moment,” he said.

Keionna Baker and Cherena Fox, who run the diversity and inclusion consultancy Elephant in the Room, agree that Kentucky has not shown sufficient progress when it comes to vaccinating Black people.

“It’s not enough growth,” Fox said. “It’s just not.”

Earlier this year, Beshear's office worked with Baker and Fox to gather information and build a public awareness campaign to "help us with an equitable rollout," he said last month.

Fox said she’s hopeful about the trajectory of Black vaccinations once that campaign is released. “I do think we're going to see a jump when the project really rolls out," she said.

Baker described the product of their work as “targeted campaign messaging” helping Black Kentuckians find the resources they need to get vaccinated.

“When it comes to any sort of messaging, it’s just important that people see people that look like them," she said.