LOUISVILLE, Ky. — At the start of last summer’s protests against the police killing of Breonna Taylor, the list of demands made by those resisting in Louisville’s streets was short enough to fit into a hashtag: #JusticeforBreonnaTaylor.

As the summer went on, the scope of their demands grew. Along with pleading for a direct response to Taylor’s death at the hands of the Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD), activists and organizers began discussing a fundamental restructuring of police, economic justice for historically marginalized groups, and other steps on the road to racial equity in Louisville.

Last June, the Louisville Metro Council enacted a tangible, policy-based response to Taylor’s killing when it passed a ban on no-knock warrants. The city later established a civilian review board for its police department and agreed to a series of police reforms in a $12 million settlement with Taylor’s family.

But upon the one-year anniversary of Taylor’s killing, the fight is far from over, local Black leaders told Spectrum News 1. Reforms in direct response to Taylor’s killing are still needed, they said, along with broader efforts to reduce inequity for the 150,000 Black people who call Louisville home.

“There has to be a complete tearing down of this racist structure and building something that’s equitable for everyone,” said Pastor Timothy Findley of Louisville’s Kingdom Fellowship Church. An active participant in the summer protests, Findley said addressing racism and racial inequities requires more than police reform.

“It's housing,” he said. “It's education. It’s poverty. I say all that to say, it’s the structure.”

One year later, the response to Taylor's killing is not yet complete. The FBI is still investigating the possibility of civil rights violations as well as the process of obtaining the search warrant on her home. And many Louisvillians are still waiting for justice, Louisville Urban League CEO Sadiqa Reynolds said. She pointed out that no one involved in Taylor’s killing has faced criminal consequences for her death.

“Justice is very slow when it comes, if it comes at all,” she said. “That’s a real challenge for our entire community."

Detective Brett Hankison is the only officer who was charged in connection with Taylor's killing. He will go on trial this summer on three counts of wanton endangerment stemming from shots he fired the night of Taylor's death. The charges, however, relate to bullets that entered other apartments, not Taylor's.

While a host of policy changes have been proposed in response to Taylor’s killing, including a statewide ban on no-knock warrants, only a few have actually been implemented.

The settlement between Taylor’s family and the city of Louisville included several police reform provisions, including measures to ensure a commanding officer approves all search warrants, new programs to incentivize police officers to live where they work, and a commitment to send social workers out on calls with police officers, when appropriate. A short-term police contract approved late last summer, included only one of these.

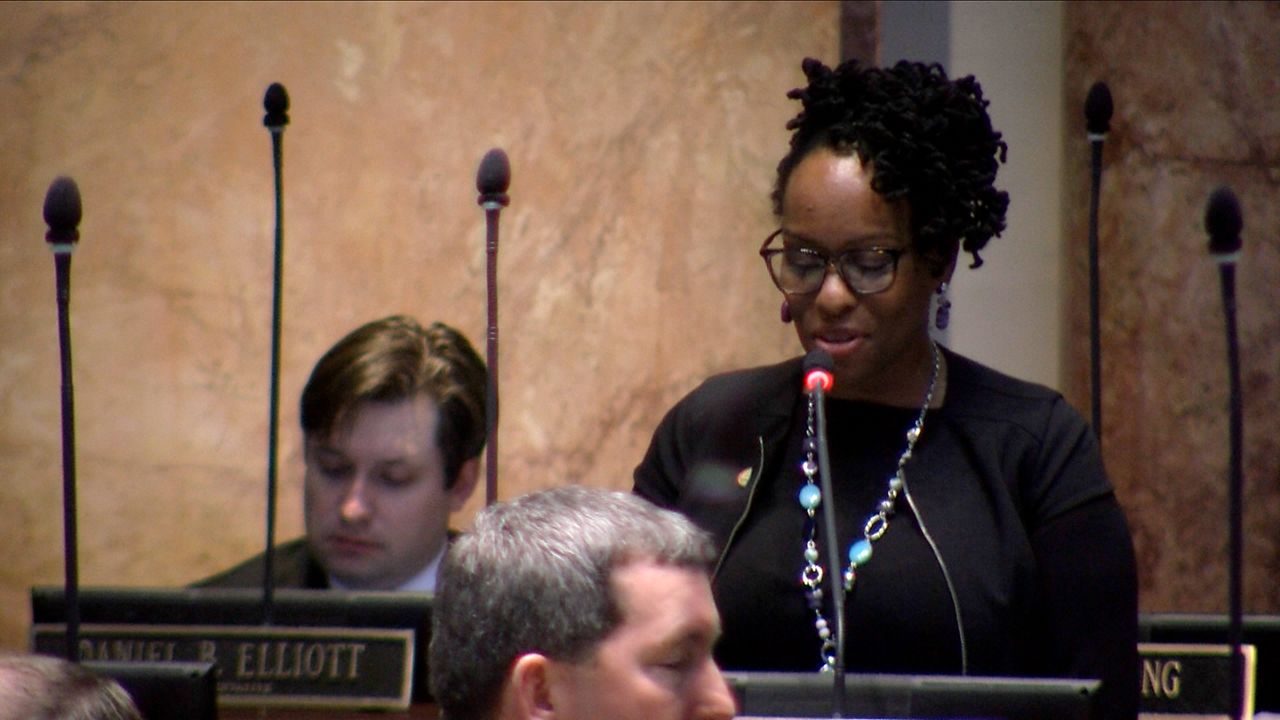

State Representative Attica Scott has introduced Breonna’s Law, which would ban no-knock warrants in Kentucky and institute several other police reform measures. After months without action, the House Judiciary Committee announced plans last week to give the bill a hearing before the end of the legislative session. It’s passage appears unlikely.

In addition to her own law, Scott said there are other measures that she would like to see become law in response to last summer’s protests. “We shouldn’t be militarizing police against their neighbors,” she said. “We shouldn't have police targeting live streamers.’

Referencing her own arrest during the protests, which lead to her being charged with felony rioting, she said, “We need to clearly define clearly in statute what we mean by riot.”

But Scott also said the mission is much bigger. “We have to address economic and social issues. Pay people a living wage. Address the fact that Black women are three to four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. Address education equity. There’s so much more that we have to do that is beyond policing, but policing has to be addressed because we’re paying people to murder us."

At Broadway and Preston Street, Kingdom Fellowship Church is a little over a mile away from Jefferson Square Park, the epicenter of Louisvlle’s protests last summer. Pastor Tim Findley knows the path between the two sites well.

Last summer, he hosted press conferences, provided parking and shuttles to protests, and was even arrested in the streets. Months later, he told Spectrum News 1 that the work he is engaged in is about changing “more than just policing.”

“We're coming together and saying, ‘We're getting hit on every side. We're getting hit in every category. There's something that has to be done,’” Findley said. “Enough is enough. We have to have wholesale change. There has to be a complete tearing down of this racist structure and building something that's equitable for everyone.”

Findley said that will include addressing issues of inequity in housing, education, economics, and health care, which he’s gotten a first hand look at in recent weeks. “We were a vaccination site a week ago,” he said. “We had over 1,000 people come to these doors.”

When he asked those who showed up at Kingdom Fellowship for a vaccination why they hadn’t gone elsewhere, he did not hear concerns about vaccine safety, but complaints about accessing vaccination sites. “It’s been hard to get to, and we made it easy,” he said.

Economic justice has been a recent focus of the Louisville Urban League, which recently opened a 24-acre sports and learning complex in the Russell neighborhood. Reynolds said the goal is to bring more economic activity to the area, creating jobs and raising property values. The challenge, she said, is ensuring that the benefits flow to those who have called that area home for decades.

“We have the challenge of making sure that as development happens in the West End of Louisville and other poor zip codes, that the people who have really had their backs broken by policy aren't just pushed out,” Reynolds said.

As local leaders envision a more equitable future for Black people in Louisville, they speak often of children who are currently attending underfunded public schools and living without the many advantages of their wealthy peers.

“Having a computer shouldn't be a luxury in the technology age,” Reynolds said. “We have to make sure that all of our children have those things.”

Local nonviolence activist Christopher 2X also emphasized the importance of working with young children, especially after the record number of homicides Louisville saw in 2020. The 173 homicides in Louisville last year were up substantially from the previous high of 117, set in 2016. Public health experts have struggled to pinpoint the cause of the rising violence, but some have suggested the economic distress created by the pandemic, the gun boom of 2020, and a lack of trust in police, leading people to take problems into their own hands.

2X said reversing the trend requires reaching children at a very young age. “The model of trying to do intervention by the time kids get in high school is out the door. It’s gone,” he said. Instead, his organization, is working with children under 10 to instill an early appreciation of physical safety.

“The goal is to teach them about the anatomy of the body,” he said. “Let them know about the body and the organs and then segue that conversation into discussing how, besides diseases and viruses hurting the body, gun play is hurting the body.”

Young people are also vital for turning cries for justice into practical change, as they ascend into positions of power and influence. Shameka-Parrish Wright, an organizer of protests over the summer, is running for mayor and Findley told Spectrum News 1 he will soon be sharing his intentions. Jecorey Arthur, an activist and educator who talks explicitly about working toward equity rather than equality, was elected to Metro Council last fall.

“I’m excited about the empowerment that I see and the voices that are being raised and what they’re saying,” Reynolds said. “I think that’s very important for us and I’m hopeful about our future.”