LEXINGTON – As the country continues its massive vaccine rollout, health departments across the country are scrambling to plan and adjust, often while simultaneously managing a slew of new COVID-19 cases.

What You Need To Know

- Main concern is number of vaccines allocated

- Small populations aid communication

- More doses planned for local health departments

- Demographics do not show many members of hesitant groups

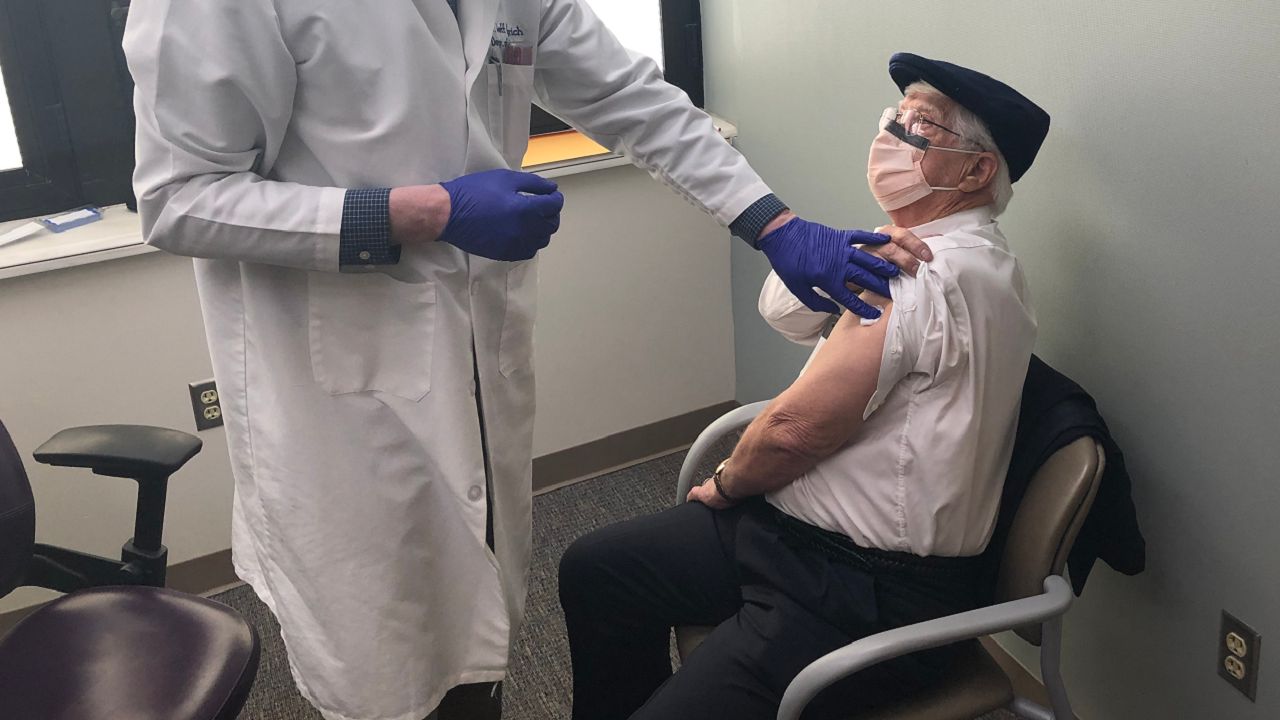

Residents in Kentucky’s rural counties tend to be older, and clinics face unique challenges getting the highly perishable vaccines and pertinent information to the more at-risk populations, many of whom often live miles away. In the face of those challenges, however, many of Kentucky’s rural counties have been very successful in administering vaccines thanks, in part, to partner pharmacies, local hospitals, and plans carefully implemented by health departments.

Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear recently announced the creation of several regional vaccination sites across the state, of which 14 of the nearly 40 are in rural Eastern Kentucky counties. The heads of some rural county governments have expressed concern over the regional sites, fearing they would decrease the already low number of vaccines going to local health departments. Kentucky Public Health Commissioner Dr. Steven Stack announced on Feb. 4 a plan to increase the doses allocated, giving 100 doses for 1% of the population in every county. Stack also said beginning Feb. 8, every local health department in Kentucky will begin getting small shipments of the vaccine over the next three weeks, giving thousands of Kentuckians much closer access to the shot. The announcement came after President Joe Biden’s COVID-19 coordinator Jeff Zients said in a White House briefing weekly doses sent to states would soon be increased to 11 million.

“I’ll just tell you the quantities are insufficient,” Stack said during the announcement. “The vaccine quantities are not enough for the task at hand, but it is still incremental progress.”

Beshear said during his Feb. 8 COVID-19 briefing, the federal pharmacy vaccination program would begin soon, and since many rural Kentucky counties are without a partner pharmacy – CVS, Walgreens, Kroger, or Walmart – there are plans to include “good neighbor” pharmacies in the plan as well.

“Walgreens is a great partner, but it didn’t have sufficient coverage in rural Kentucky, so we advocated for the program to include independent pharmacies, too,” Beshear said.

The problem across the board, however, is there are not enough vaccines to administer.

Kentucky’s rural counties, by most standards, have been very efficient in distributing the vaccines as a result of using local health departments, regional sites, and hospitals even with considerable logistical challenges and the lack of the required cold storage capacity.

Lee County, about 75 miles southeast of Lexington, is a small, rural county with a population of just over 7,400 with 17% of residents age 65 or over. Lee County Judge-Executive Chuck Caudill said he is pleased with his county’s vaccine distribution plan, which involves coordination with the Kentucky River Health District that serves Lee and six other counties.

“The vaccinations for 70 and older have begun and, in discussions with local health agencies, hundreds have signed up and there will be a steady flow of vaccine doses coming into Lee County every week for the foreseeable future,” he said. “This is a huge logistical challenge for everyone as priorities change, the number of vaccines change, and the dose sizes change. It has to be given twice with about a month between doses, and the need to store the vaccine at such low temperatures makes it a rush to get it in as many arms as possible without wasting any once they are thawed.”

Caudill said he speaks with Kentucky River Health District Director Scott Lockard and Lee County Health Department Coordinator Vivian Smith daily about any conflicts that have arisen and he reads Beshear’s COVID-19 briefings ad nauseam.

“We are like any other county in Kentucky and I’ll tell you what every other judge-executive in Kentucky will tell you, and that is we don’t have enough,” Caudill said. “We're all saying that because we would all like more. The reality is that the logistics of trying to give two doses and storing it at sub-zero temperatures is difficult. When it comes to so many doses, where over the course of the past few weeks the number of doses increases or decreases, then the priorities of teachers over another group of essential workers changes it is very confusing, but I would say that every reasonable effort is being made to mitigate the logistics problems and every reasonable effort has been made to minimize confusion.”

Lee County has administered hundreds of vaccinations, Caudill said, and the distribution has specifically addressed first responders, other essential personnel, and teachers.

“This week, we started on the 70-and-older group, and as I understand it, every week there's going to be more vaccines rolling in the area,” he said. “I'm talking to the people that they are calling on the list, and they are bringing them in to get their shots, being sent back out and waiting for 15 minutes, and being told they will be called back for the second shots in 20 to 30 days. It’s a major logistical undertaking, but I think everybody from the government, to the CDC and the manufacturers, all the way down to the health departments is doing their absolute best to ensure the people who need this vaccine, and want it, because that's the key element still for some reason, are going to have access to it.”

Caudill said he knows of several Lee County residents that signed up to be vaccinated at the regional sites at Appalachian Regional Hospital in Hazard about an hour away and Baptist Health in Richmond.

“I think the bottom line is how much do you want people to congregate because we probably don't want to do that,” he said. “I think we've got health departments in every county that have health directors who know what they’re doing. Perhaps we should let the health directors and health departments come up with a plan they think is the best.”

Getting vaccines in the arms of residents in rural counties is made easier for several reasons, Caudill said, which are fewer residents, familiarity, communication, and demographics.

“Distrust multiplies when you get to the larger populations and the opportunity for miscommunication increases,” he said. “The natural propensity of people is you tend to mistrust people you don’t know. We don’t really have to deal with minority groups that are hesitant to get the vaccine, like the urban counties, because we have such a small minority population – our minority population consists of two or three families.”

Pike is the largest rural county in Kentucky in both area and population. Its nearly 60,000 residents are served by two hospitals, Pikeville Medical Center in the county seat and Tug Valley Appalachian Regional Hospital (ARH) in South Williamson, located 28 miles away in the more densely populated area of Pike County along the West Virginia border. Gov. Beshear and the Kentucky Department for Public Health have complimented the system Pikeville Medical Center (PMC) is using to register and vaccinate people in the region, which is currently scheduling around 2,000 people per week. PMC CEO Donovan Blackburn is urging people wanting the vaccine in its seven-county service area to “please be patient.”

“I realize there are so many people in the community that want this vaccine and we want to give it to them,” he said. “There are a lot of logistical challenges with it and a lot of pieces of the puzzle that have to come together for us to make this work. We knew when these vaccines were made available, it could take months, or up to a year to vaccinate everyone, and we are at the mercy of allocation.”

In addition to its Pike County location, ARH operates 10 other hospitals and clinics throughout Eastern Kentucky. Roy Milwee, ARH CEO of Ambulatory Services, said the hospital system is administering a little more than 1,700 vaccines per week even with the current fluctuation in the number being allocated.

“Once [allocation] levels off, it will allow us to better plan, organize, and so forth,” he said. “Without a consistent schedule of the shipments, it makes it a little tougher on us from a resource standpoint, but overall, I think our processes are good.”

Milwee said more than 300 vaccines were administered on Feb. 10, in Hazard in Perry County, and more than 1,000 system-wide. Cumulatively, more than 21,000 first and second doses have been administered at ARH sites.

“I think for what we're getting, that's a good number,” he said. “We still have thousands signed up and signing up on our website.”

Milwee said logistical issues are something to which small, rural hospitals have grown accustomed.

“From a logistical standpoint, we're used to our geographic footprint,” he said. “We're used to figuring out how to get doses from one community to another community and shipping those out – all of our doses are shipped straight to our Hazard location, and then we have to send those out to all the different communities in eastern Kentucky. We are doing that routinely, at least weekly, and sometimes more than once per week, depending on when we get the vaccines. So we've always been really good at that we have to do it on a routine basis. We're getting great feedback from our patients. I think people are excited about this. They're happy to get it and they're thankful for what we're doing."

The cost of hosting vaccine sites – both financially and in terms of personnel – is some cause for concern, Milwee said.

“Today, with our current processes, we're going as fast as we can, and, I think, long-term we’ll need resources. We'll need to look at how we're doing things, and particularly the funding piece of it, to make sure we have the abilities to keep doing it the way we are today,” he said. “We're pulling a lot of our staff from their real full-time jobs and having them do this type of work. And yes, we want to do it. It's good for our communities and we want to be part of that solution to this virus. But, at the same time, it does put a financial burden on the organization and to those departments that these employees are coming from, so we need to figure out how we maintain this financially.”