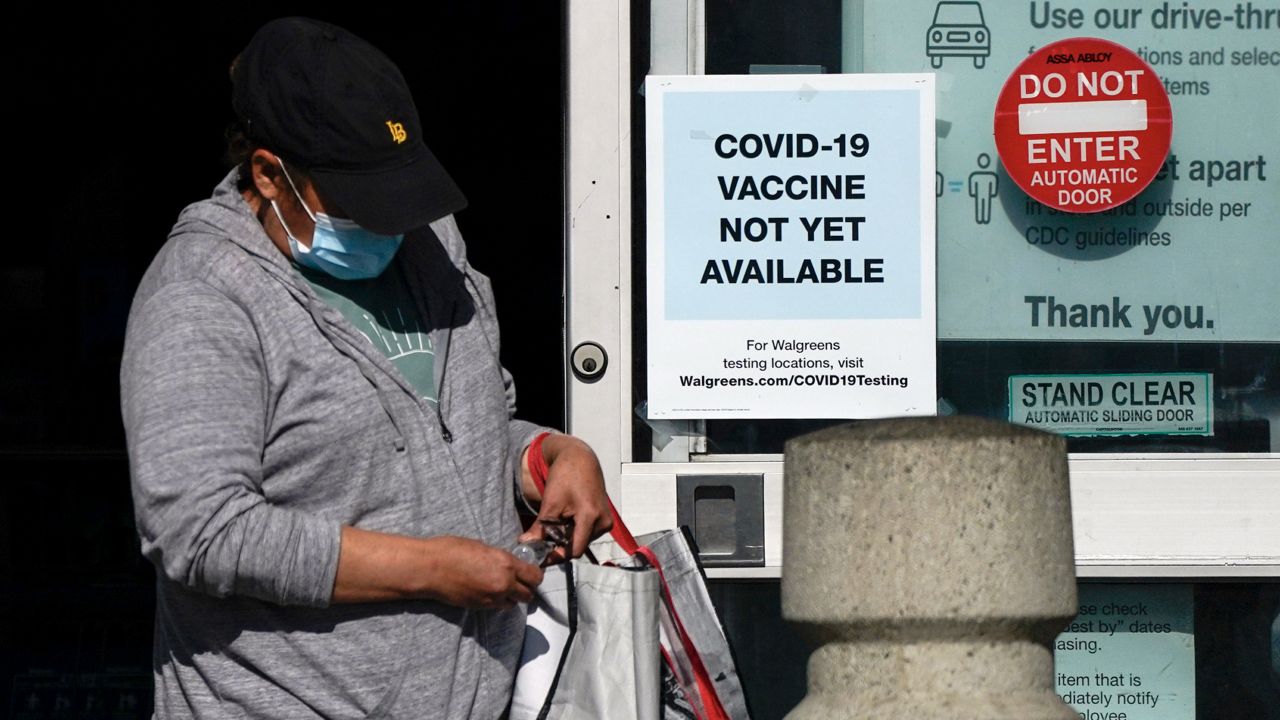

DURHAM, N.C. — Coronavirus vaccines, which could be approved by the middle of this month, have been called a “light at the end of the tunnel.” But there’s a lot of planning and logistics involved once the vaccine manufacturers get the green light to start distributing the vaccines to the states.

State public health departments across the country are preparing their own plans to get the vaccines out quickly as many areas are seeing record numbers of new cases and people hospitalized with COVID-19.

This will be the biggest vaccination distribution program in United States history, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit focused on health care issues.

“We need to be excited and pleased where the science has got us in a very short period of time,” Thomas Denny, chief operating officer of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, said during a call with reporters Thursday.

But, he added, “Manufacturing and scale-up is a challenge, when you think about the number of doses that need to be produced.”

Every state has set up a task force to figure out how to distribute coronavirus vaccines, but some are further ahead in their planning, according to Kaiser.

“Some states have already begun the process of signing up providers to administer COVID-19 vaccines and building out existing immunization registries, while others are still just developing plans,” Kaiser said in a report this week.

There are two vaccines before the FDA for emergency approval, from Pfizer and Moderna. Both vaccines have shown to be about 95% effective in clinical trials.

If both vaccines are approved as expected this month, as many as 40 million doses of vaccine could be shipped by the end of the year, Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said last month.

Each state and territory is in charge of their own vaccination plan, following guidelines from federal public health officials. Generally, health care workers and hospital staff working directly with COVID-19 patients or in high-risk areas like emergency rooms will be the first to get the vaccine.

States have some leeway in what groups get priority on receiving the vaccines, but generally the highest risk groups, like staff and residents in long-term care facilities and people with chronic conditions, will be some of the first in line to get vaccinated.

After the first batches of the vaccines are distributed, more shipments are expected on a weekly basis.

In North Carolina, for example, the vaccine will be shipped first from the manufacturer to a limited number of hospitals, according to Dr. Mandy Cohen, secretary for the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services.

As more vaccine doses become available, more hospitals will receive shipments, she said. Vaccinations for staff and residents in long-term care facilities like nursing homes will be handled by a separate federal program, but the doses will still come out of the state’s allotment, Cohen explained.

Distributing the Pfizer vaccine will be more difficult because it has to be stored at very cold temperatures, colder than a typical freezer.

Pfizer has apparently overcome those challenges and plans to distribute the vaccine with dry ice, so not every hospital will have to spend the money for new specialized freezers, Cohen said.

Adding to the logistical complications for public health departments, the vaccines will require two doses. And that means states will have to track who got vaccinated, with which vaccine and when.

Then they will have to make sure people come back for the second shot. The Pfizer vaccine needs a second dose at 21 days and for the Moderna vaccine it's 28 days.

It could take months to vaccinate enough people to protect communities.

“I see 2021 as a transition year. As we begin to get more people vaccinated—and I think it’ll take us at least into the second quarter, end of second quarter to see large numbers there—slowly we’ll come out of the social distancing, and less masking,” Denny said.

There are also a number of unknowns about the vaccine, including how many people will be willing to take it and how long it could last to keep people safe from the virus.

Denny said researchers don’t know yet if people will need to get a booster shot after a year or get another vaccine five years down the road.

“There will be studies that will continue. What we call the long-haulers type of approach where you continue to follow people and look for long-term protection,” he said.

Another big question is about using the vaccine on children. The clinical trials so far have been on healthy adults. Moderna announced Wednesday that it was preparing to start testing its vaccine on children.

The vaccines will likely not be available for children anytime soon.

“It will be key to get clinical trials performed in children to learn if vaccines are safe and effective. One day this may be part of a well-baby immunization schedule, where at a certain age you’d receive this vaccine as you would receive other vaccines,” Denny said.

Dr. Gavin Yamey, with the Duke Global Health Institute, said, “We have excellent vaccination programs and delivery channels for reaching children, ready to go now. And one way to reach herd immunity more quickly would be to vaccinate children. It could take a long time to set up these delivery channels for older people. They don’t really exist now.”

“I think there is some urgency about knowing the safety and efficacy of children,” Yamey said in a call with reporters Thursday.