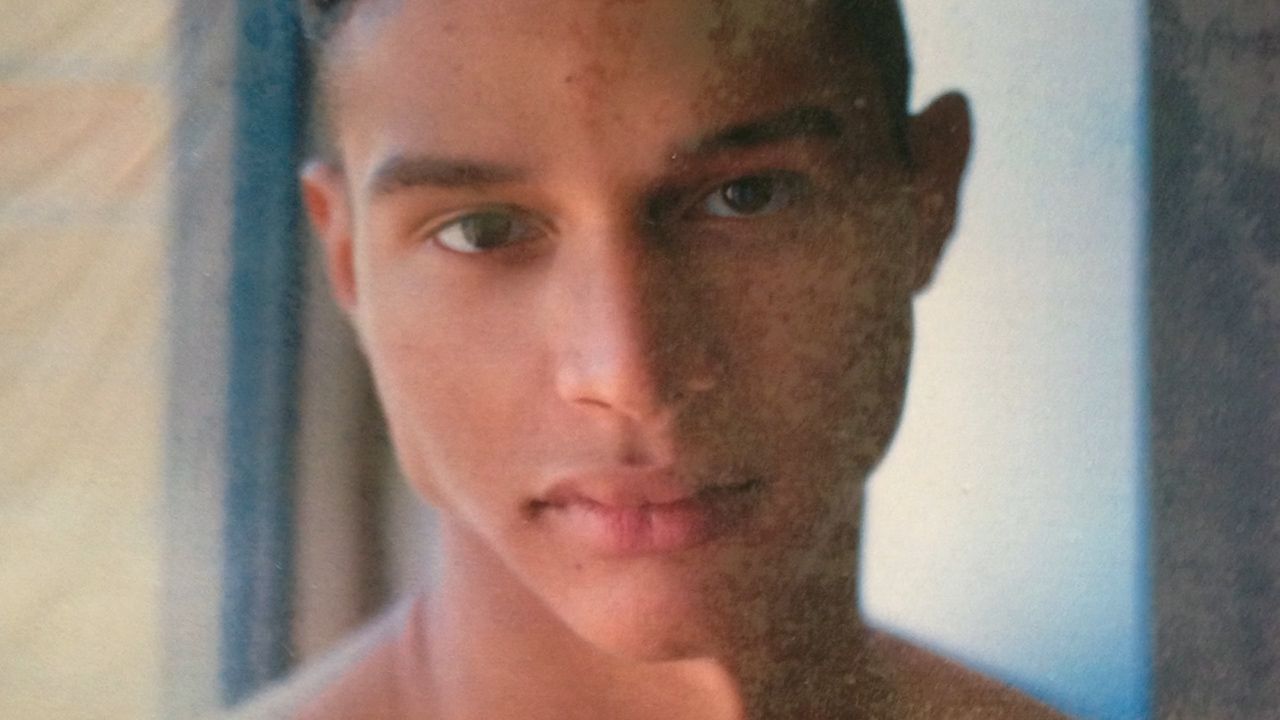

Two years ago, David Strait suffered a debilitating stroke. The incident robbed him of 15 years of memories. At 55 years old, the structural designer is still numb on his right side.

“My life is split in two. There was the person I was before my stroke whom I don't know, you know," Strait said. “And then there's this person after the stroke that woke up who is two year and a half years old.”

Unable to work, his 22-year-old son Orion cared for him.

A year into Strait’s recovery, Orion died in his sleep on Christmas Eve. The aspiring model had struggled with an opioid addiction.

“He was just a ray of light to everybody,” Strait said of his son. “I'd give up everything to see him for a minute, you know.”

Strait said that the grief and depression were just too much, so he reached out for help: “I just didn't know how to live anymore without Orion. I didn't want to die, you know? But what I did know is, I didn't want to live.”

Strait was hospitalized and released just as the coronavirus pandemic worsened, becoming another barrier to in-person care.

But Strait was able to keep in touch with his doctors at NYC Health + Hospitals / Bellevue through telehealth sessions.

“It was a relief. You know, I didn't have to expose myself,” said Strait. “It worked with me over the phone. You know, it's a lot safer.”

As with Strait, the pandemic forced many more into isolation: Use of wellness apps skyrocketed, proof that maintaining good mental health is a growing priority, particularly during a crisis.

Strait’s psychiatrist at Bellevue, Dr. Meera Balasubramaniam, says the need for serious mental health services also grew.

“The number of referrals we received certainly increased during the course of the pandemic,” Dr. Balasubramaniam told Spectrum News. “Then there were others who may have had worsening symptoms in the context of the global pandemic.”

Many hospital systems and private practices have risen to the challenge, with the help of fewer barriers. Early on in the pandemic, the federal government allowed emergency access to telemental health services. As a result, insurers began covering the sessions at the same or close to the cost of in-person visits.

Dr. Steven Siegel, chair of the University of Southern California’s department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, said the changes have been eye opening.

"This has been, I think, one of the most significant moments in mental health care and health care in general," Dr. Siegel said. "Everything we knew about the limits of telehealth turned out to be overblown."

Across the country telehealth is becoming an accessible option for patients who previously never received therapy, like USC graduate student Nikitha Kolapalli.

"Coming from India they didn't even believe that I had a mental health issue," Kolapalli said. "So when I was young and I was depressed and I was traumatized, they just took me to a temple."

Kolapalli said she found healing through video visits offered through USC’s Student Health Services. During the pandemic she was diagnosed with bipolar and anxiety disorders.

“I do feel that virtual is really comfortable because you just get up and down on a camera,” said Kolapallli. The sessions have helped her put past trauma into perspective, and she said she feels she’s regained control of her life. “It was really dark. But now I can see the light.

Even before the pandemic, there was a demonstrated need for tele-mental health services.

In the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 5% of those who needed mental health services, but hadn’t received them, cited transportation issues. An additional 20 percent said they simply did not have time.

But while patients like Kolapalli and Strait were able to get care remotely, the pandemic is also shining a spotlight on a remaining obstacle: The so-called digital divide.

“What we see is there are well-off patients who have their own space, their own apartment,” said Siegel. “But there are others where even if they have connectivity, say, through a mobile device, they don't have access to a place that is private and secure.”

Siegel said he hopes the access to care, which was forced open by the pandemic, remains an option for those who enjoy remote treatment: “What health systems in general can do is come up with good rubrics for what has to be in person, what really should not be done in person and what's in between.”

Siegel added that includes forcing insurance companies to fully-cover telemental health sessions after pandemic allowances have lapsed.

“We have good evidence that it works fine," Siegel said. "There's no reason that health care insurance companies should revert back to disincentivizing this kind of access to care.”

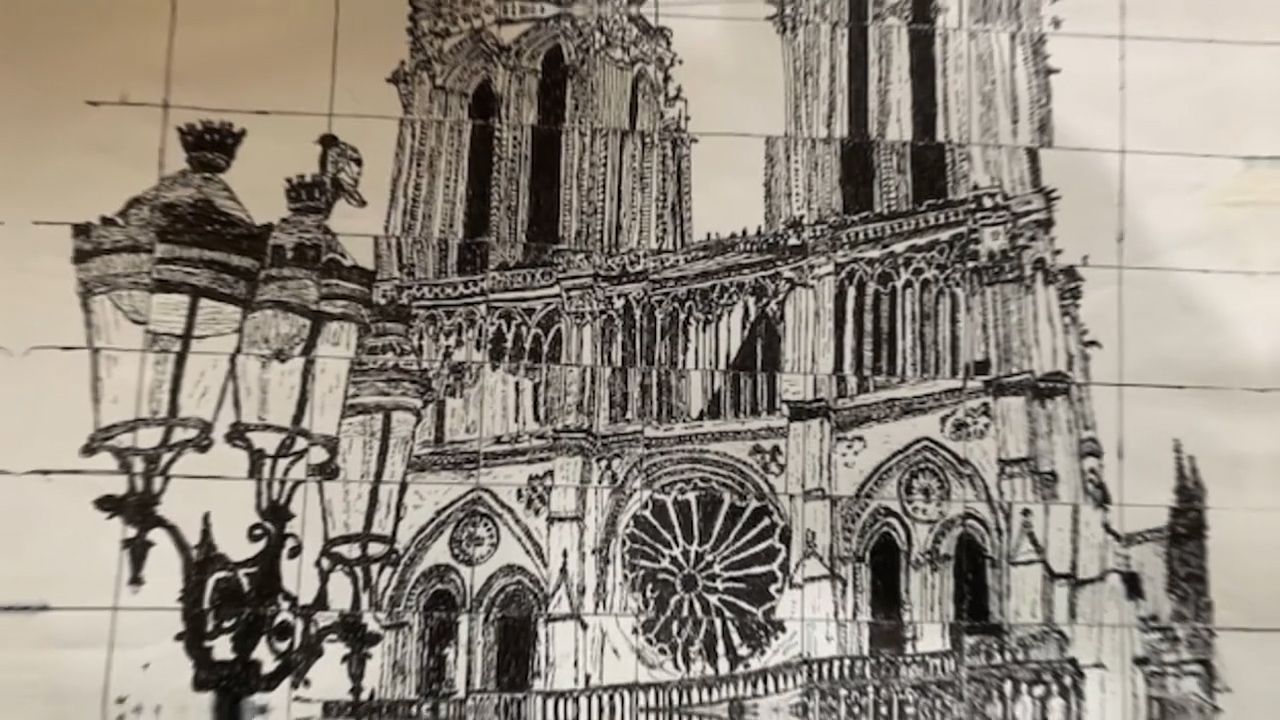

Meanwhile, Strait said he may not go back to in-person sessions. During his treatments, he found a new purpose through art and feels his care over the phone has worked.

“They taught me how to, you know, to have another day and that's really all we need is one day, you know,” Strait said.