LOUISVILLE, Ky. — The Louisville Defender is the city’s oldest newspaper still in operation, which has a focus on the city’s Black community. The Defender will celebrate its 90th anniversary this March and still puts out a weekly issue, which will cost you 75 cents per copy.

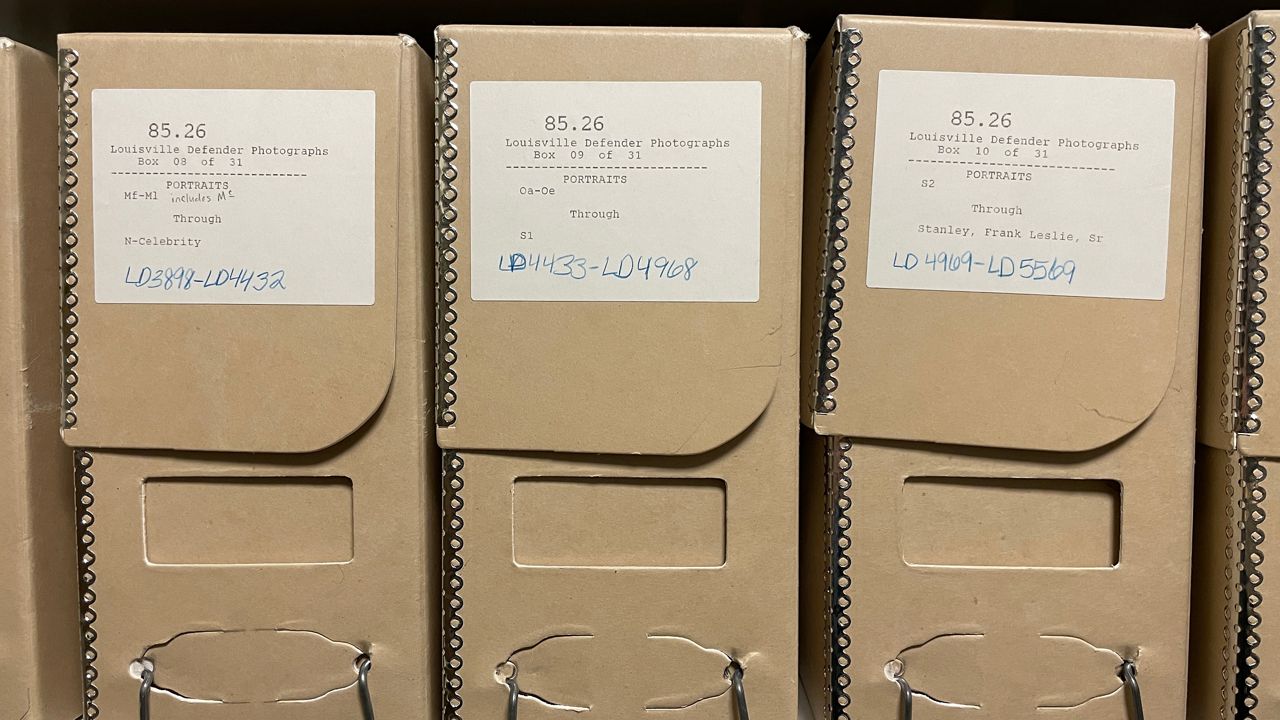

Much of the paper’s photo archive has been lost to history. The largest collection of photographs is housed in the UofL Ekstorm Library’s Special Collections Department. The collection, of over 16,000 prints, is part of the Frank L. Stanley Sr. Papers.

However, there is a problem. Many images in the collection are missing important information.

“We have the image, but we don’t know who it is or who took the photo or actually when it was taken,” said Elizabeth Reilly, photo archive curator at the University of Louisville.

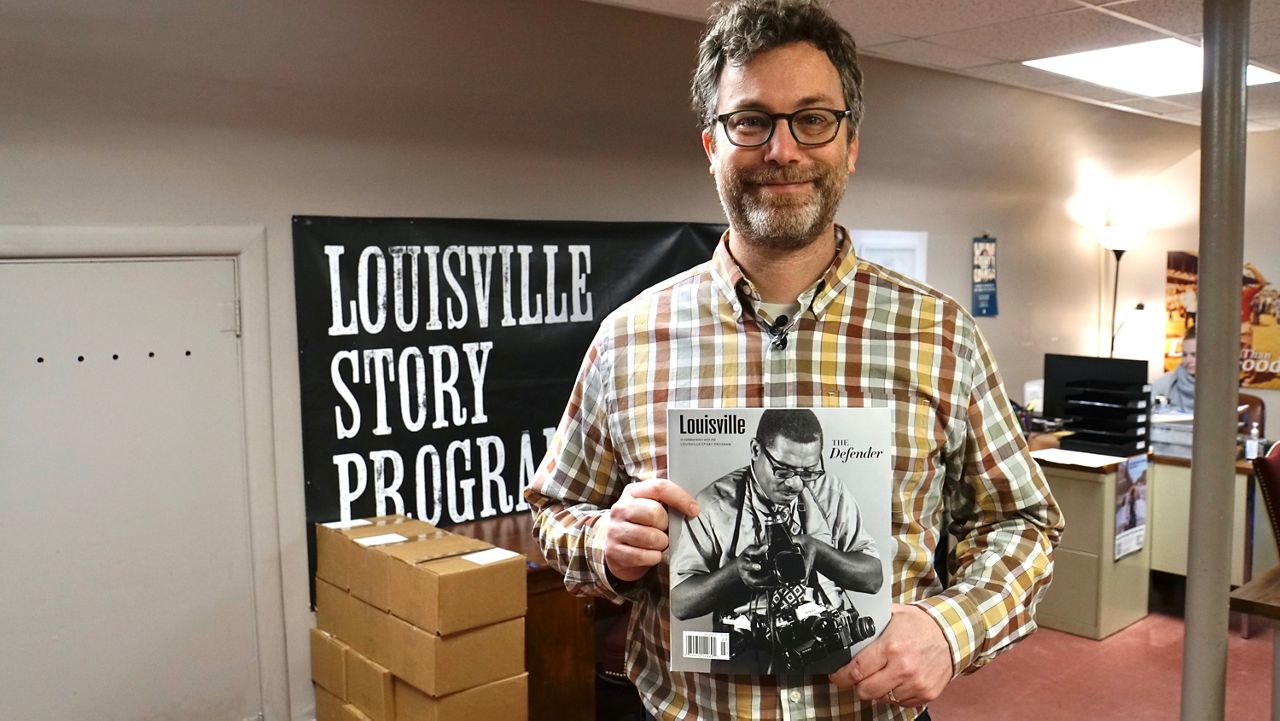

One organization, the Louisville Story Program, is trying to correct this.

“Hopefully we can make a lot of these connections and get a lot of this information to be reunited with the images,” said Darcy Thompson, executive director of the Louisville Story Program.

The organization, which has documented Louisville’s underrepresented communities for a decade, is asking members of the community if they recognize the people and locations seen in the photographs. They’re also asking if people know who captured the images.

This work, Thompson explains, is to give people more context to the world captured by The Defender’s team of photojournalists.

“There is a lot of knowledge in our community and of the folks with that knowledge can encounter the photos, and talk about what they recognize, and that can be recorded or written down, you know, and coupled with the photo online, whenever they have it online,” Thomson said. “That would be just great for our community as far as better understanding our history.”

The Louisville Story Program worked for over a year with a company digitizing the photo archive at UofL. Eventually, these will be available online, but there is currently no timeline for when that’ll happen.

During that year, the Louisville Story Program quite literally wrote the book on the Defender, highlighting its long history and showcasing images produced by the paper.

Their work was featured in a Dec. 2022 issue of Louisville Magazine, which you can read an excerpt from below.

Another organization working to preserve the work of The Defender is the Louisville Free Public Library. Decades of weekly issues are now available online, so long as you have a city library card.

“To have that at your fingertips and not [go] searching through a folder to see if you can find some mystery article, it’s amazing to be able to offer that to the community at large,” said Natalie Woods, manager of the Western Library branch.

The library will have Defender issues from the 1950s to 2010.

With a library card, people will also be able to access archives for other Black newspapers. This includes the Chicago Defender, Michigan Chronicle, and Philadelphia Tribune.

“Had we had that resource when we were putting together the magazine, we’d have been able to track more things down and have more captions than we did,” Thompson said. ”That work of looking at the photos and looking at the old issues and making connections can also lead to more information and captions and more photographer attributions.”

Previously, these past issues were only available on microfilm.

At UofL, the Stanley Sr. collection is open to be viewed by the public through the Special Collections department.

Through the work of the Louisville Story Program and the Louisville Free Public Library, decades of work by the Black photojournalists, reporters and staff of the Louisville Defender will be easily accessible for decades to come.

The Louisville Story Program asks anyone who can provide some of the missing information from the Louisville Defender photographs to reach out to their organization.