WASHINGTON, D.C. — White House officials were so determined this summer to present an argument for why children should return to in-person classes that they pressured the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to downplay the risks and tried to circumvent the agency as they sought out alternate data to help bolster their public case, according to a report.

The New York Times reported Monday that Trump administration officials spent weeks pressing public health professionals to fall in line with the president’s agenda of reopening schools and the economy as quickly as possible. The newspaper cited documents and interviews with current and former government officials for its reporting.

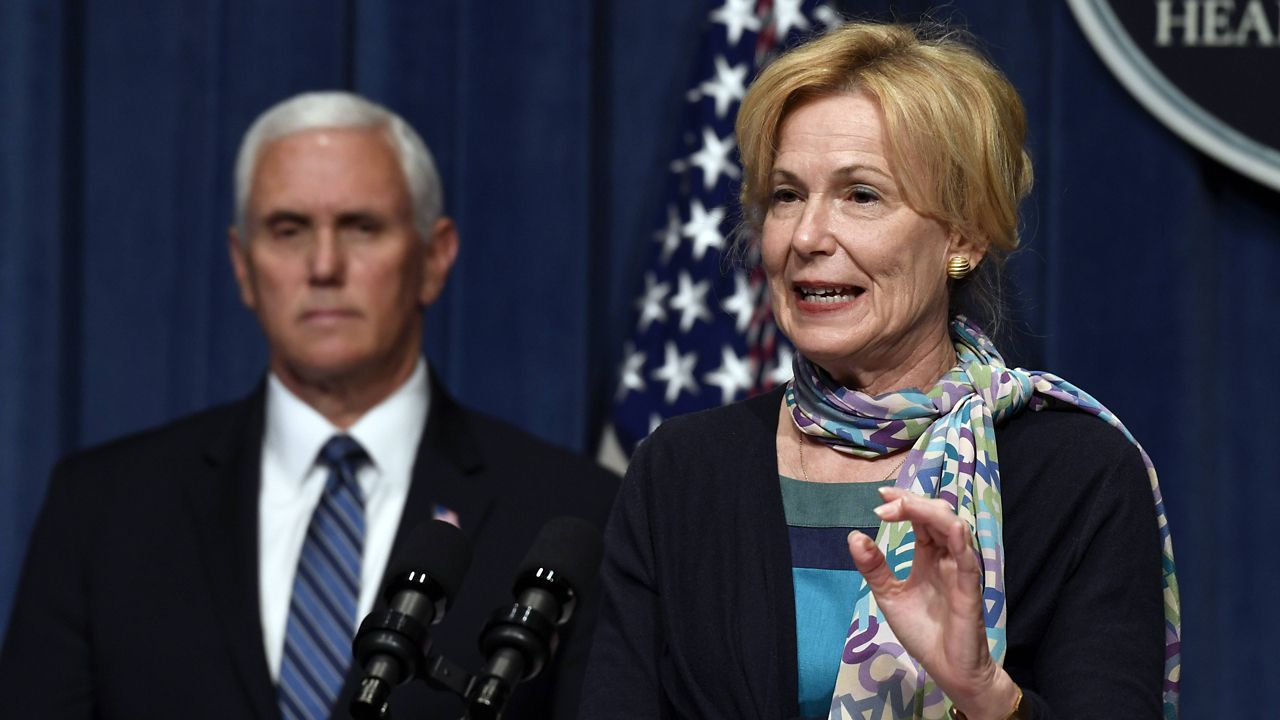

The pressure campaign, led by White House coronavirus response coordinator Dr. Deborah Birx and aides to Vice President Mike Pence, left CDC officials alarmed, the Times reported.

Olivia Troye, one of Pence’s top aides on the White House Coronavirus Task Force, said she regretted being “complicit” in the effort, adding she tried to shield the CDC as much as possible.

Troye, who has since left her position and has spoken out publicly against Trump, said that Marc Short, Pence’s chief of staff, repeatedly asked her to get the CDC to produce more reports and charts showing a decline in coronavirus cases among young people.

Troye said she believes the goal was to reopen schools before voters cast their ballots.

“You’re impacting people’s lives for whatever political agenda,” she told the Times. “You’re exchanging votes for lives, and I have a serious problem with that.”

The Times reported that the internal struggle began in July as the CDC was drafting its guidance to help parents decide whether to send their kids back to school. The agency’s draft acknowledged that scientists were “still learning about how” the virus spreads, “how it affects children and what role children may play in its spread,” and that limited data suggested that children were less likely to get the virus than adults.

It also warned of deaths caused by multisystem inflammatory syndrome and of increased risk of severe illness for certain children. And it recommended that parents weigh the safety of others who live in their households.

The draft asked parents to “consider the full spectrum of risks involved in both in-person and virtual learning options,” according to the Times.

Birx then began to press the CDC to incorporate work from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a little-known mental health agency that developed a document warning that school closures would have a long-term effect on the mental health of children. It also said there were very few reports of children being the primary source of coronavirus transmission among family members and that asymptomatic kids were unlikely to spread the virus.

CDC scientists found numerous errors in the document and believed it minimized the risk school-age children faced, the Times reported. While the CDC successfully fought off some of the changes, the mental health agency’s position stressing the potential risks of children not returning to classrooms became the preamble of the CDC’s policy, which angered some officials at the agency, according to the newspaper.

The final document, titled “The Importance of Reopening America’s Schools This Fall,” included information that CDC officials had initially objected to, the Times reported.

White House spokesman Brian Morgenstern told the Times: “President Trump relies on the advice of all of his top health officials who agree that it is in the public health interest to safely reopen schools, and that the relative risks posed by the virus to young people are outweighed by the risks of keeping children out of school indefinitely,” Morgenstern said.

The CDC has not commented.

Trump, who has admitted to downplaying the coronavirus in the past, had publicly been saying at the time he wanted all children to return to in-person instruction full-time and even threatened to withhold funding from school districts that did not cooperate. The president at one point falsely claimed that children are “almost immune” to the virus.

Since then, there has been growing evidence that children, while less vulnerable to the virus than older people, can still be at risk for serious illness and spread the virus to others. Data from the American Academy of Pediatrics shows that hospitalizations and deaths from the virus have increased among kids and teens at a faster rate than the rest of the general public. A South Korean study found that children ages 10 to 19 can spread the virus at least as much as adults do.

The Times report is not the first alleging the Trump administration has pressured the CDC to alter its work to match Trump's interests, which is sure to raise further questions about the public health agency’s independence and credibility at a time when coronavirus cases in the United States have topped 7.1 million cases and the death toll is more than 205,000.