There were signs Sunday that negotiators were closing in on a deal at a U.N. conference that would protect nature and provide financing to set up protected areas and restore degraded ecosystems.

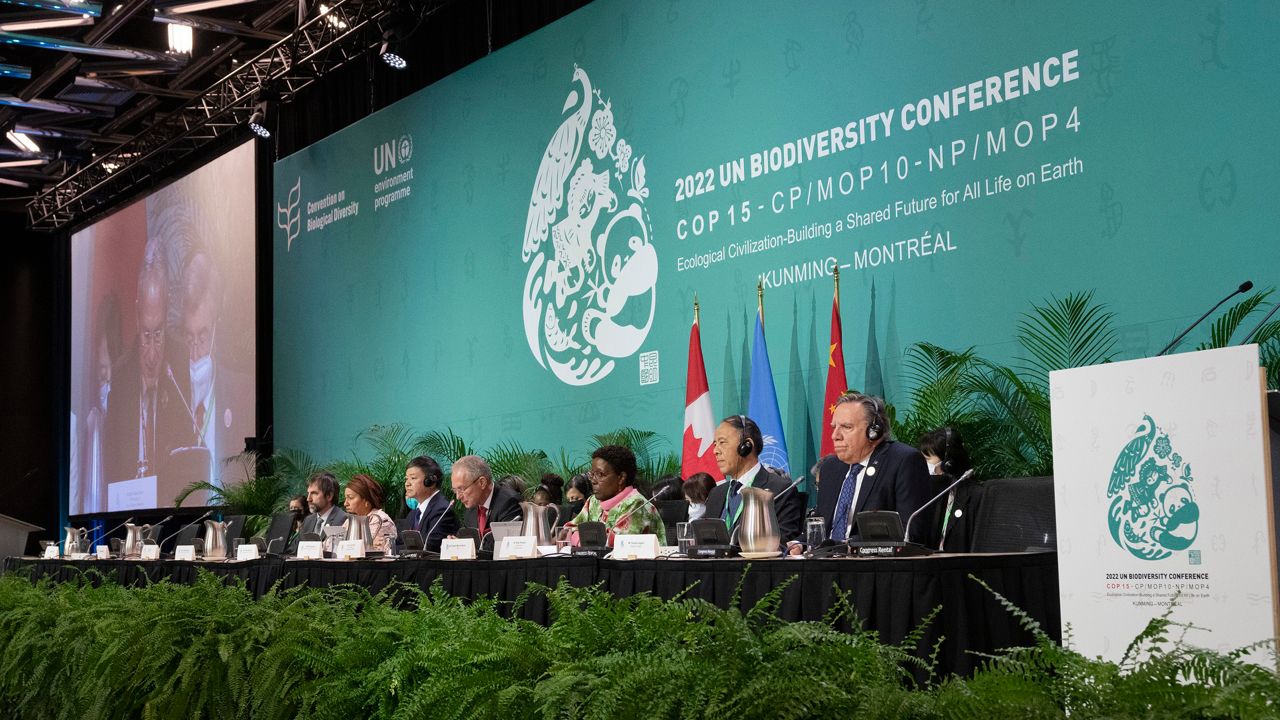

China, which holds the presidency at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference, or COP15, released a draft deal that calls for protecting 30% of the most important global land and marine areas by 2030. Currently, 17% of terrestrial and 10% of marine areas are protected.

The draft also calls for raising $200 billion by 2030 for biodiversity and working to phase out or reform subsidies that could provide another $500 billion for nature. As part of that, it calls to increase to at least $20 billion annually or by some estimates triple the amount that goes to poor countries by 2025. That number would increase to $30 billion each year by 2030.

The draft now goes to a meeting of all governments this evening and could be adopted soon after.

“Today the world’s countries rose to the occasion and produced a historic draft that agrees to protect at least 30% of our planet," Enric Sala, National Geographic Explorer in Residence and Pristine Seas Founder, said in a statement. "This recognizes years of work by negotiators, researchers, conservationists, and Indigenous Peoples. Now we just need to maintain the political will to get this ambition across the finish line without diminishing its scope. World leaders must remain committed to bold action in Montreal.”

The ministers and government officials from about 190 countries mostly agree that protecting biodiversity has to be a priority, with many comparing those efforts to climate talks that wrapped up last month in Egypt.

Climate change coupled with habitat loss, pollution and development have hammered the world’s biodiversity, with one estimate in 2019 warning that a million plant and animal species face extinction within decades — a rate of loss 1,000 times greater than expected. Humans use about 50,000 wild species routinely, and 1 out of 5 people of the world’s 8 billion population depend on those species for food and income, the report said.

But they have struggled for nearly two weeks to agree on what that protection looks like and who will pay for it.

The financing has been among the most contentions issues, with delegates from 70 African, South American and Asian countries walking out of negotiations Wednesday. They returned several hours later.

Brazil, speaking for developing countries during the week, said in a statement that a new funding mechanism dedicated to biodiversity should be established and that developed countries provide $100 billion annually in financial grants to emerging economies until 2030.

“All the elements are in there for a balance of unhappiness which is the secret to achieving agreement in U.N. bodies,” Pierre du Plessis, a negotiator from Namibia who is helping coordinate the African group, told The Associated Press. “Everyone got a bit of what they wanted, not necessarily everything they wanted. Let's see if there is there is a spirit of unity.”

Others praised the fact the document recognizes the rights of Indigenous communities.

“By including strong language safeguarding the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities and recognizing Indigenous and traditional territories, the text provides an opportunity for a new era of partnership, respect and rights-based conservation,” Brian O’Donnell, the director of the Campaign for Nature, said in a statement. “This could be the paradigm shift that scientists and Indigenous leaders have been calling for.”

But others were concerned that the draft puts off until 2050 a goal of preventing the extinction of species and preserving the integrity of ecosystems.