Toe-tapping and head-bobbing are inevitable when listening to the "King of Ragtime’s" songs. They’re so compelling and familiar that one is even a famous ice cream truck jingle.

But the music that American composer Scott Joplin hoped would captivate audiences remained largely silent for decades until long after his death: an opera called “Treemonisha.” Joplin wrote the opera years after “Maple Leaf Rag” had become a nationwide hit.

He based the story on what he witnessed himself—a childhood shortly after the Civil War, in an area of Texas not far from the borders of Louisiana and Arkansas. His father was a former slave.

It’s been called the nation’s first true opera.

“It’s the only expression of African-American life in the Reconstruction Era that exists - that’s created by someone who lived through that time period, actually experienced it,” said Rick Benjamin, founder and director of the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra, who wrote a companion book to his orchestra’s recording of “Treemonisha.”

“That in and of itself makes it an amazing document.”

The opera is set on a plantation near the Red River “somewhere in the State of Arkansas,” as Joplin writes in a detailed preface. After the Civil War ended, whites left the plantation, leaving the remaining freed slaves “in dense ignorance,” as Joplin puts it in language that some may find offputting today.

The community is superstitious, taken with “conjuring.” But a young Black girl, found under a tree by a childless couple and then educated by a white family, leads her neighbors out of their waywardness, becoming their teacher and leader.

She is Treemonisha.

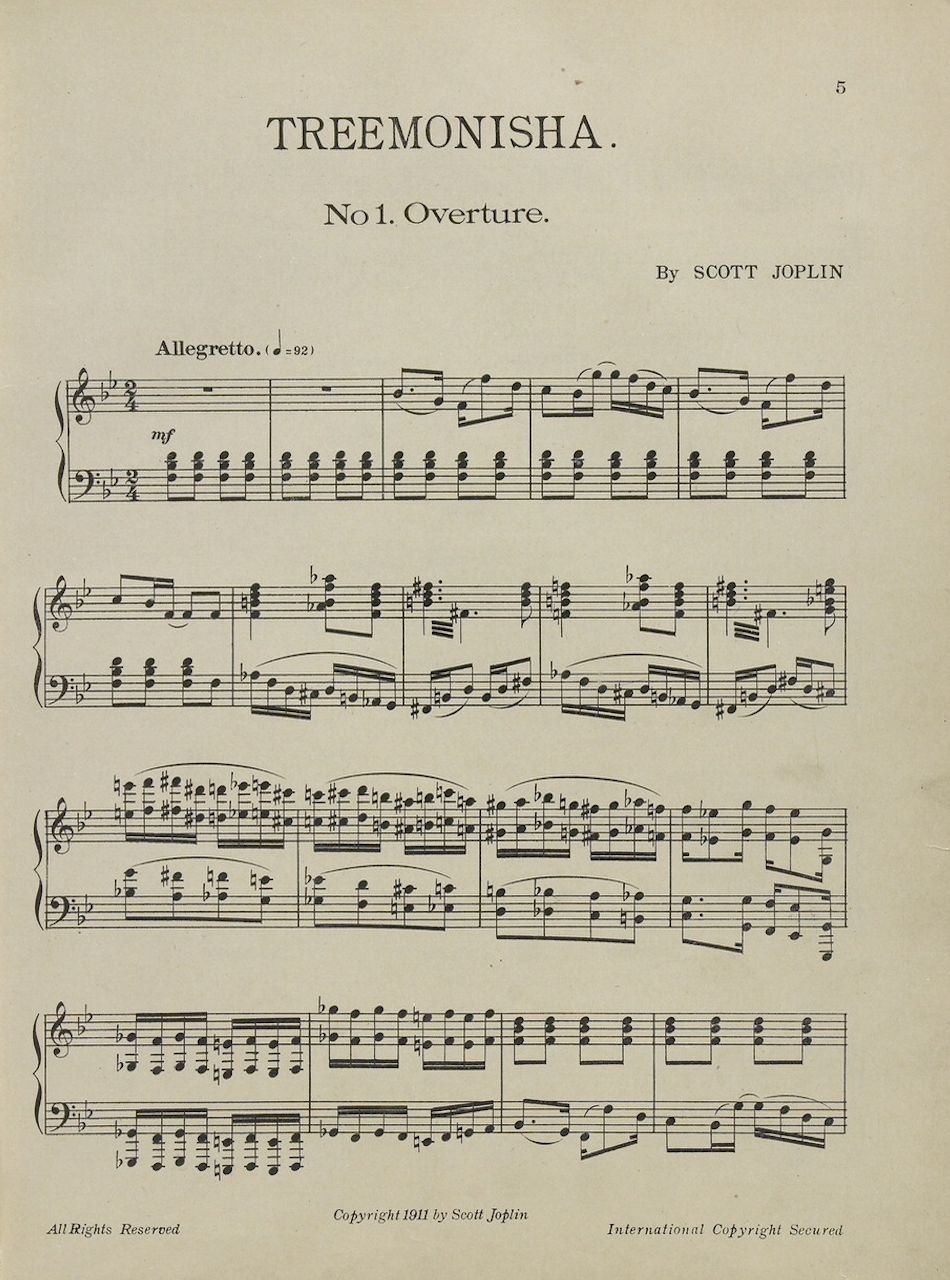

Joplin is thought to have started writing in a St. Louis rooming house, finishing it in a Manhattan apartment that’s now a hotel. But despite his ragtime acclaim, publishers rejected the opera. Joplin was forced to print the music himself; then cast it too.

Despite his efforts, Joplin never saw a major production.

“It’s a work that has had a very troubled history. And it really—it wasn’t something that achieved success during his own lifetime,” said Benjamin.

In 1917, six years after copyrighting the opera, Joplin died, destitute, buried in an unmarked grave with two strangers. Friends blamed Joplin’s disappointment over Treemonisha for his death.

“After his death, it really just vanished completely from the scene,” Benjamin said.

“Nobody believed in the work,” added longtime composer T.J. Anderson. “I mean, a black opera written by an American composer—that was just beyond their thinking.”

It took decades for its resurrection.

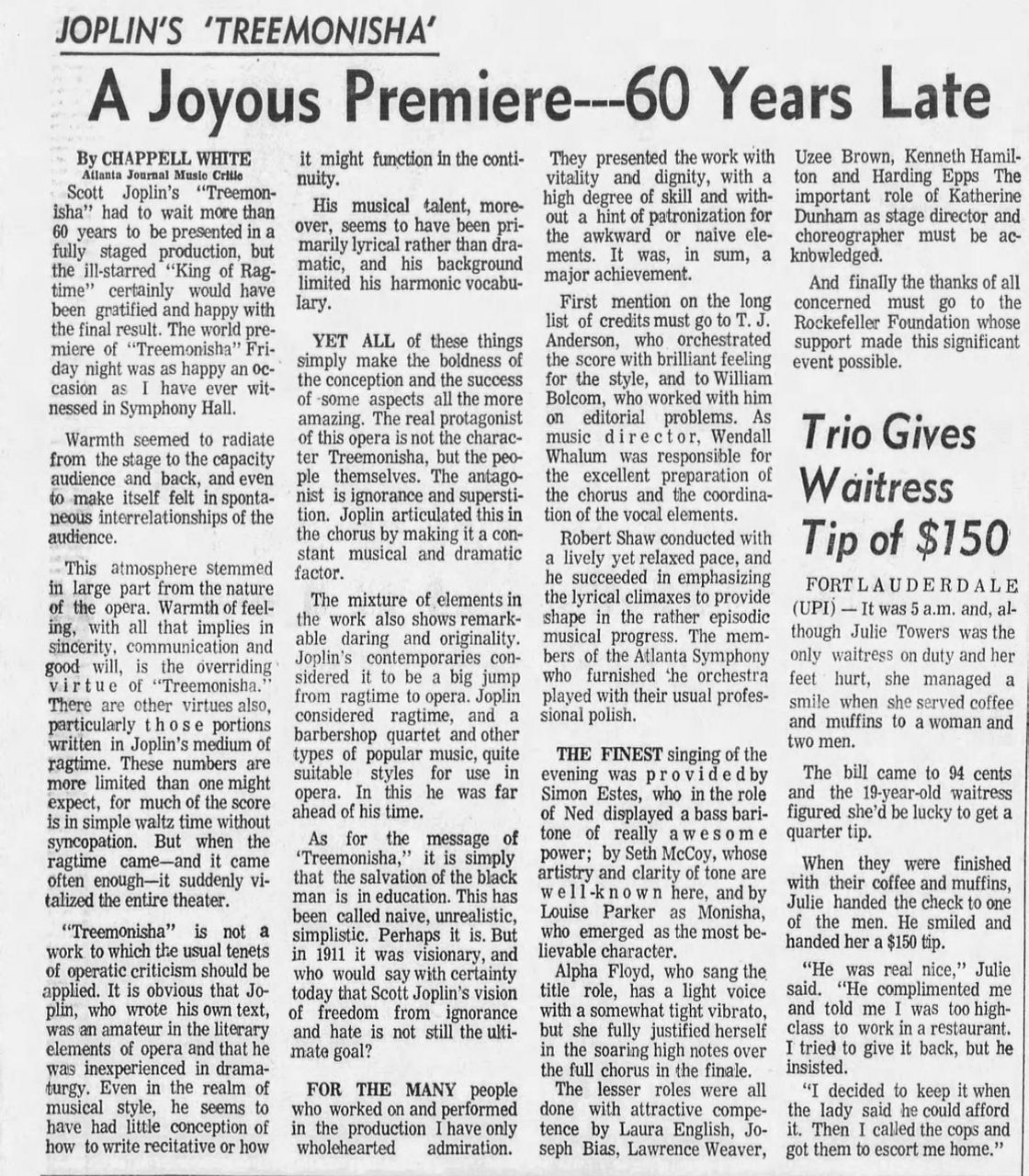

Fifty years ago exactly, “Treemonisha” rose from the dead.

“OK, ready. OK, so we’re going to hear your performance,” this reporter told the trio of musicians.

That was the 1972 performance—the first known “Treemonisha” performance since Joplin’s death.

We were at an assisted living facility in Atlanta, where Anderson lives, joined on a chilly December morning by two others who were in the ensemble: Uzee Brown and Laura English-Robinson, who both went on to distinguished careers in academia.

The revival drew from students at Morehouse College and Spelman College, as well as Atlanta musicians. It generated plenty of buzz and curiosity.

Brown, an undergraduate member of the Morehouse Quartet, says a mentor told him about it: “And his excitement was passed on to us, though we weren’t quite sure what we were supposed to be so excited about. We just knew that something big was on the rise.”

Indeed, big names were involved—the conductor Robert Shaw, director of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and Katherine Dunham, choreographer and stage director.

Still, there was a glaring problem. The lone music to survive was a rehearsal book, with notes only for piano. That was more than a prior Joplin opera—its music has never been found.

Anderson was tasked with translating what he believed Joplin would have wanted “Treemonisha” to sound like. He turned to operas performed by itinerant musicians of the era, especially in New Orleans.

The revivalists in Atlanta started rehearsing.

“We didn’t want to present anything that we hadn’t given our whole self to,” English-Robinson said. “We didn’t want to present anything that would be remembered as ‘Well, it was OK.’

“No. It was really good. The energy that was on stage and the energy that was received from the audience, it was a beautiful opportunity.”

Indeed, dispatches from the evening have the audience dancing in the aisles and demanding (and receiving) numerous curtain calls after the endlessly captivating “Real Slow Drag” final number.

“There were just so many things about it that marked it as something significant historically,” Brown said, “but it became more significant later on when I understood how very special that opera was compared to the whole of American music and music in general.”

Joplin’s opera finally had an audience—and it couldn’t get enough of “Treemonisha.”

There is no single answer why the adoration took decades. In the early 1970s, long after Joplin died in a pauper’s grave, his ragtime music resurfaced; pianist Joshua Rifkin’s “Scott Joplin: Piano Rags” climbed to the top of the charts. The New York Public Library published his collected works. And later that decade, the soundtrack for “The Sting,” with Paul Newman and Robert Redford, famously was replete with Joplin’s music.

The era was also a time of awakening of African American power and pride—especially in the hometown of Martin Luther King Jr., who was assassinated in 1968.

Coretta Scott King was in the audience that Friday evening, and among other notables was Maynard Jackson, who the next year would be elected Atlanta’s first African American mayor.

Said Brown: “This is a truly positive story about a woman who is a liberator for her community through education, and the dismissal of superstitions and the importance of understanding as the aria says, as Remus sings, that ‘wrong is never right.’ You can never justify the incorrectness in terms of how you treat your fellow man.”

“Treemonisha” earned Joplin a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1976. Though far less known than his rags, the opera is occasionally performed—a Broadway production fizzled for complicated reasons, according to Joplin biographer Ed Berlin. Behind the scenes, “Treemonisha” sparked a lively debate about what instruments Joplin would have used.

Its historical relevance to the history of Black America is clear; but “Treemonisha” also carries a universal theme.

“The education aspect speaks to everybody because that’s a form of having a roadmap to advancement,” said Anderson. “My father used to tell me, ‘Son, if you want to succeed in life, you go to school.’”

Berlin also declares: “it’s not a thrilling opera - it has some boring parts to it. But there are other parts that are great, that are fabulous.” (Indeed, the overture and finale are mesmerizing).

Still, the plot, and language, may strike some as discordant today. For instance, Joplin pointedly writes a white family educates Treemonisha, allowing her to vanquish her community’s “ignorance.” At least one performance after 1972 also apparently changed Joplin’s lyrics, which often include a dialect seen as common among African Americans in that era.

The artists in Atlanta bristled at the changes and concerns.

“After slavery, there were a number of whites that went south to educate African Americans,” Anderson said. “This is a fact. I mean, I’m not talking fantasy, I’m talking facts. And of course, they were welcome.”

Noting the language his own grandparents spoke, Brown added: “You know, you can’t dress it up and make it something that it is not for the sake of being politically correct for a contemporary audience. It was right for that time.”

Their hope is that the opera is kept alive—and performed on the nation’s biggest stage: New York’s Metropolitan Opera, which is not far from where Joplin wrote “Treemonisha.”

It was only in 2021 that the Met performed an opera by a Black composer, when it opened its season with “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” composer Terence Blanchard’s adaptation of Charles M. Blow’s memoir.

The Met didn’t return a request for comment, but Anderson emphasized his dream:

“What should occur is that its historical significance alone should cause the Metropolitan Opera to present it as an opera—with no revisions.”

“That would be my dream — that the opera would be treated as an opera and it would be performed as Joplin intended.”