For a topic that dominated headlines in the first half of 2021, the issue of immigration was largely absent on Wednesday from the dozens of questions asked at President Joe Biden’s second press conference since he took office.

The peak of border apprehensions has subsided and the number of unaccompanied immigrant minors in government care has stabilized – while the sweeping immigration plan Biden put forward in his first month as president no longer appears to be on the drawing board.

Yet while immigration has faded from top of mind for some, President Biden has acted the issue in a slew of ways — including 296 executive actions, to be exact, according to a Migration Policy Institute tracker — much of it undoing former president Donald Trump’s hardline policies.

And at the same time, the rebuilding, restructuring and re-emergence of the U.S. immigration system that many advocates hoped for remains a hefty goal, and there is still room for the administration to work on stemming the flow of migration at the southern border, rebuild the refugee system, address refugees and military allies and implement true systemic reform.

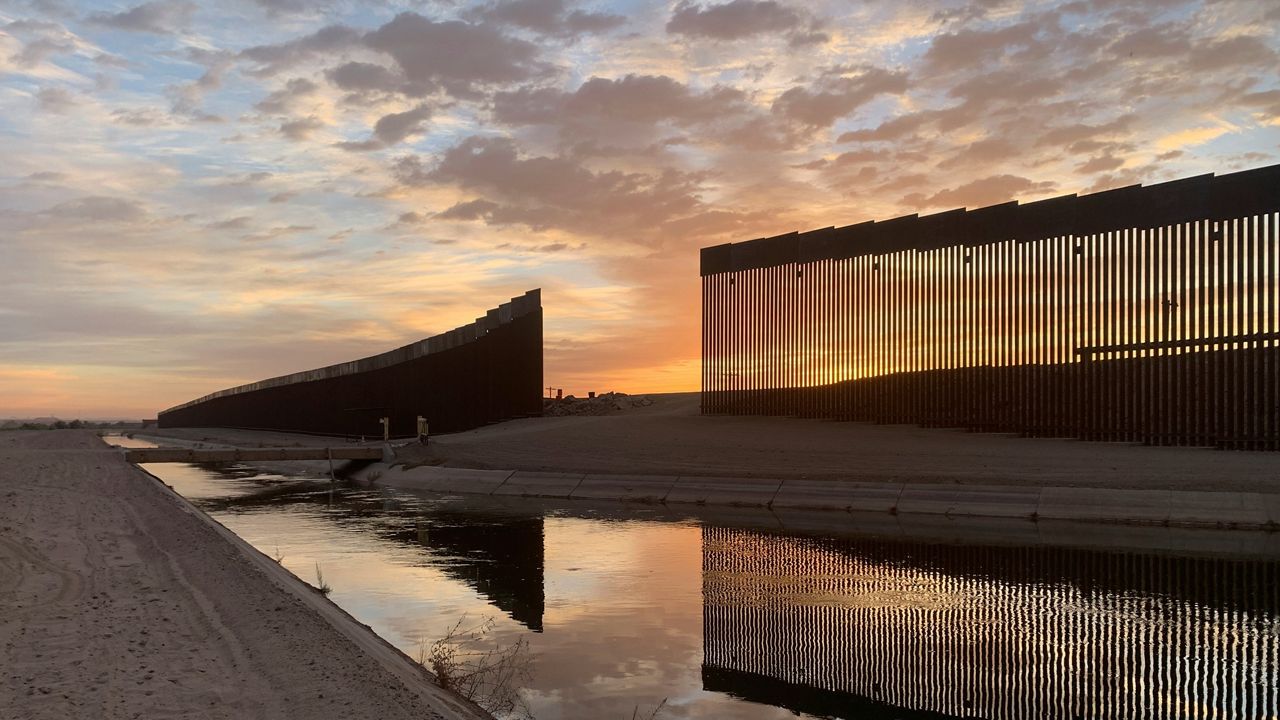

The U.S.-Mexico border quickly became the most visible flashpoint of the immigration debate under President Biden, as last spring a combination of seasonal migration, conditions in Central America and a perception of the Biden administration as more lenient all pushed more people toward the United States’ southern frontier.

In fact, fiscal year 2021 ended with 1.7 million border apprehensions, the most ever recorded in a single year. The number of unaccompanied minors especially outpaced records.

However, about a million of those were immediately turned away under Title 42, a coronavirus pandemic-justified health order that led to more repeat attempts at crossing the border, yet another contribution to the high number.

Biden’s handling of the border has been criticized by both sides: Republicans have seized on the border chaos and record numbers while Democrats and immigration advocates condemn the continued use of Title 42 and call for comprehensive reform to the system.

Republicans led their own trips to the border last spring and summer to point to how border agents were overwhelmed. President Biden has yet to visit the border.

“This needs to stop. It is a crisis, it is a tragedy, and it is a man-made crisis,” Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, a staunch critic of the president, said after touring the overcrowded tent facility in Donna, Texas, last March.

Advocates, meanwhile, have been disappointed in an administration that promised a different approach to immigration and asylum but has instead expelled hundreds of thousands of people.

“The White House has adopted a defensive posture on all things border, ceding the rhetorical framework to the Republicans and embracing and even expanding Trump's deadly anti-asylum border policies,” said Lorella Praeli, co-president of Community Change, in a media briefing Wednesday.

One example still at issue is the “Remain in Mexico” policy, which requires migrants to wait outside the U.S. while their asylum case is processed, a Trump administration rule that left thousands of people in dangerous, tenuous conditions for months on end. The Biden administration has been legally required to continue the policy.

“We completely agree with everyone that says that there is no way that this can be done humanely,” said Esther Olavarria, a key immigration adviser on Biden’s Domestic Policy Council. “[We] are doing everything that we can to make it different from what was done under the Trump administration.”

Vice President Kamala Harris was tapped by the president to oversee the root causes of migration, mostly from countries south of the U.S. border like El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico.

Her work has also been met with scrutiny on both sides: Republicans have highlighted her lack of attention to the border itself, while advocates bristled at her unwelcoming message to people hoping to migrate, despite being a child of an immigrant herself.

“I want to be clear to folks in the region who are thinking about making that dangerous trek to the United States-Mexico border: do not come,” she said at a press conference in Guatemala last summer. “Do not come.”

The Vice President's team has emphasized that her mission to address root causes will take time. Harris has announced more than a billion dollars in private investments in Central America so far and has also visited Mexico and Guatemala. She plans to travel to Honduras later this month.

Of the 296 executive actions Biden has signed so far, 89 have focused on undoing the work of his predecessor, who atrophied several aspects of the immigration system. But Biden has also left many in place as attention to immigration waned in 2021.

One major reversal was the travel ban that restricted even temporary visits from Muslim-majority countries starting 2017, separating families and blocking thousands of people from the U.S. based on nationality alone.

But the resumption of visas from those countries under Biden has been slow. Nearly one full year after Spectrum News spoke with Hadi Haghighat — who was living in Iran, separated from his parents and brother in the U.S. — he reported that he finally booked his flight to join his family this month after joining a lawsuit and paying legal fees around $5,000.

“This was not an easy process,” he told Spectrum News in a Whatsapp message.

Inside the country, President Biden’s administration has also altered how immigration is enforced.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), for example, is no longer directed to deport any person living in the U.S. without documentation, as it was under President Trump.

“The mantra of the [Trump] administration became that every unauthorized person should be looking over their shoulders every day,” said Muzaffar Chishti, a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, in a briefing Wednesday.

The Department of Homeland Security is now focusing on removal of “noncitizens who are a threat to our national security, public safety and border security.”

More changes will take time and a greater, administration-wide effort.

“It is hard to explain to somebody who hasn't worked there how broken DHS is on a normal day,” said Elizabeth Neumann, who served as the department’s deputy chief of staff under Trump.

“Any time you change administrations, there's a lot that gets thrown up in the air, and you’ve got to figure out how to move things forward.”

President Biden ended his first fiscal year with the lowest number of refugees admitted into the country since the program was created in 1980: 11,411.

That figure is partially because of the pandemic and an added effort to evacuate Afghans to the U.S. in late summer, but it’s also reflective of a refugee program infrastructure decimated under Trump, who set the lowest cap on refugees in history at 15,000.

Biden raised that cap to 62,500 for 2021 and 125,000 for 2022, plus a roadmap to restoring the refugee program, but the rebuild has proved difficult.

“We have seen too little action to enact these changes,” said Lacy Broemel, a policy analyst at the International Refugee Assistance Project, which published a report this week with recommendations to restore the program.

And like the past two administrations, Biden has fallen short on protecting specific categories of people who need refuge: Afghans and Iraqi interpreters who served with the U.S. military overseas and face direct threats for their work with Americans.

Iraqi allies can only apply for a visa through the backlogged and rigorous refugee program, through a special priority category, but approvals have been scarce, and there are hundreds of thousands of people in the application pipeline. The program was also paused for months earlier this year due to security reasons.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of Afghan allies and their families were left behind when the U.S. military carried out its chaotic exit from Afghanistan.

The Biden administration did evacuate more than 120,000 people from the country, and 76,000 have arrived in the U.S., including more than 62,000 who have resettled in American communities. They are in the country under humanitarian parole, which is temporary, and will have to go through the asylum process for permanent status.

Broad and lasting changes to the immigration system have remained elusive for Democrats.

President Biden put forward on his first day in office a sweeping plan for immigration reform: creating a roadmap to citizenship for the 11 million people living unauthorized in the country, expanding employment-based visas, adding border technology and an inter-agency plan to address the root causes of migration.

But talks on Capitol Hill disintegrated, and now Democrats are attempting to pass some citizenship measures through reconciliation — the complicated legislative process being used to pass Biden’s major social spending bill that doesn’t require Republican votes. But those efforts also seem tenuous now.

Some groups like Dreamers — immigrants who came to the U.S. as children without documentation — have bipartisan support and could receive protections through Congress more easily.

But like other major pieces of Biden’s agenda, the idea of passing a broad, bipartisan package appears increasingly unlikely.

“When I have been in government — and that has been now more than 18 years — I realize everyday how difficult it is to enact change,” said Olavarria, the current Biden adviser on immigration.

“There's a lot of work that we have done that I am very, very proud of, and there's a lot of work that is still underway.”