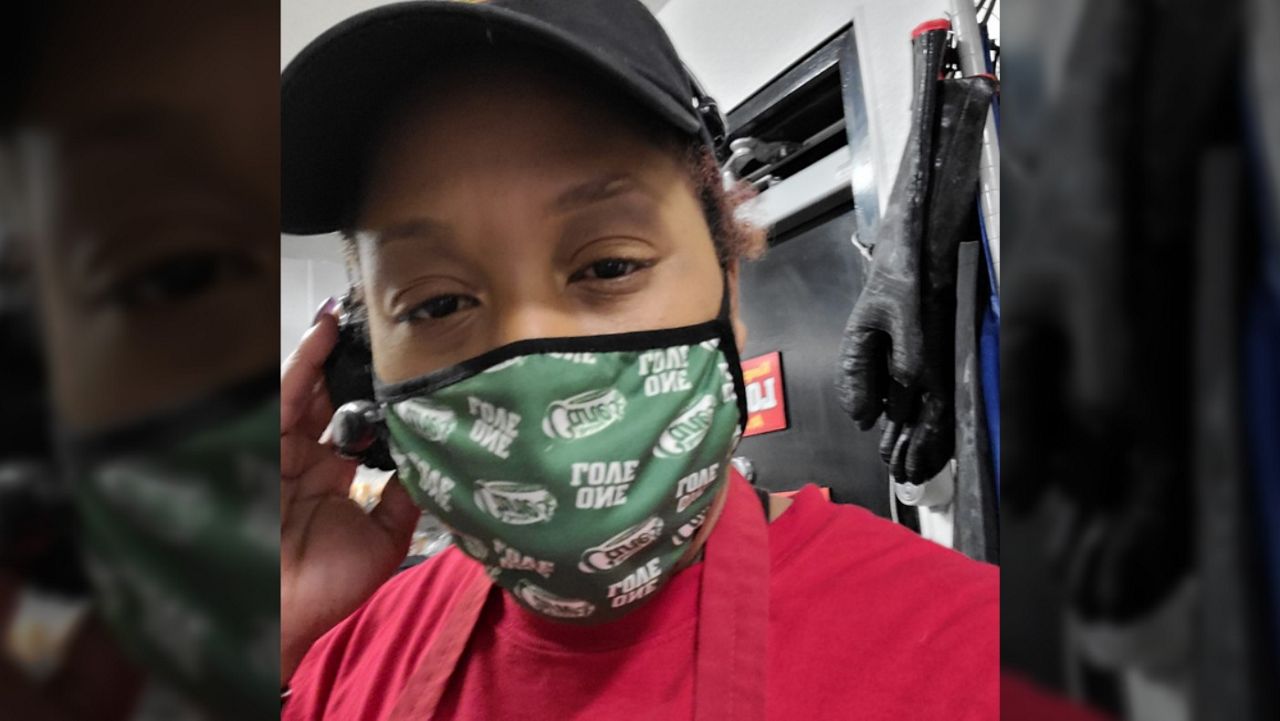

NATIONWIDE — It’s late afternoon in St. Louis when Monique Jamison appears on Zoom. Her eight-hour shift serving chicken fingers at a fast food restaurant still clings to her, she says.

“I have flour everywhere, my body's tired, my feet aching, my back hurting,” she says.

Then there’s the smell — she says when she leaves work, work won’t leave her. It’s not pretty, she admits with a rueful laugh. What is it? “Basically dead bird, bird juice, grease, outside trash, lemon juice, coleslaw,” she says.

“It's not worth it, but I love my job,” she says, now starting to cry. “I love my customers, my coworkers — that's what makes me stay.”

“Not the pay,” she says, a laugh between tears. “Bank account on negative.”

“I mean, it’s terrible, and we shouldn’t have to live like this.”

Tomorrow at 8 a.m., Jamison begins another shift at Raising Cane’s on Hampton Avenue. Another full eight hours — and still, her work carries the stubborn contradiction that often comes with a job in a cheap restaurant: giving nourishment to others means you won’t have enough for yourself.

Jamison lives with her 12-year-old son who “eats like a grown man.” Sometimes, even with government assistance, she says there’s not enough money left over for the two buses she takes.

“I've been struggling,” she says. On most days, she brings home $92 before taxes.

That works out to $11.50 an hour — about $4 more per hour than the current federal minimum wage, which is $7.25 an hour.

Tamra Kennedy checks off memories of childhood meals: stray cabbage grown in fields her family passed; government cheese and macaroni.

“Before the world got better at understanding the way to help food insecure people, you used to have a special colored meal ticket, which meant you were poor,” she says.

“I was that child.”

She is about 550 miles north of St. Louis, outside of St. Paul, Minnesota, talking about how what we now call food insecurity persisted into adulthood. Even when Kennedy had a steady job as a secretary in a fast food franchise, trips to the grocery store ended in tense standoffs as the register beep-beep-beeped.

"I would make the choice between an eight pack of soda and three packs of Kool-Aid in the grocery cart,” Kennedy says. “I only had so much money, where I knew to the dollar how much my grocery bill could be or I was not going to make it.”

That was in 1984; she was making $4 an hour — about $10.30 in today’s wages, or about $3 more than today’s national minimum wage.

Kennedy thinks about those times now. Her philosophy is colored by years spent not knowing what her next meal would be. In that, she is much like Jamison.

But Kennedy is now responsible for 122 twice-monthly paychecks in the eight Taco John’s fast food restaurants she owns in Minnesota and Iowa.

And she and Jamison sharply diverge over a matter roiling Congress and the nation: the proposal, supported by President Joe Biden, to raise the national minimum wage to $15 an hour.

The history of minimum wage in America

It was called a “Fireside Chat," but there was no need for extra warmth when the president took to the radio.

“This is one of the warmest evenings that I have ever felt in Washington, D.C.,” Franklin Delano Roosevelt said.

It was June 24, 1938, and despite the rumble of war from afar and economic ruin from within, Roosevelt sounded relieved — and for good reason. The Democrat had recently signed long-sought legislation capping the official work week at 44 hours and creating a national minimum wage of 25 cents an hour.

A quarter in 1938 is less than $5 today — well below the current $7.25 minimum wage. But at the time, progressives saw it as a triumph for American workers. Individual states had passed minimum wage legislation beginning with Massachusetts in 1912; but action at the federal level had faced decades of resistance, including from the Supreme Court.

Then, there were protests from business interests, which Roosevelt dismissed in his address that warm June night.

“Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day, who has been turning his employees over to the Government relief rolls in order to preserve his company's undistributed reserves, tell you...that a wage of $11 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry,” he said.

The workweek was later amended to 40 hours, and the federal minimum wage has been raised more than 20 times — most recently in 2009 — with 30 states and Washington, D.C., along with numerous localities, also setting their own higher rates.

Still, one constant over the generations is the fierce debate that is unleashed anytime a proposal to boost the minimum wage gains traction.

Like right now.

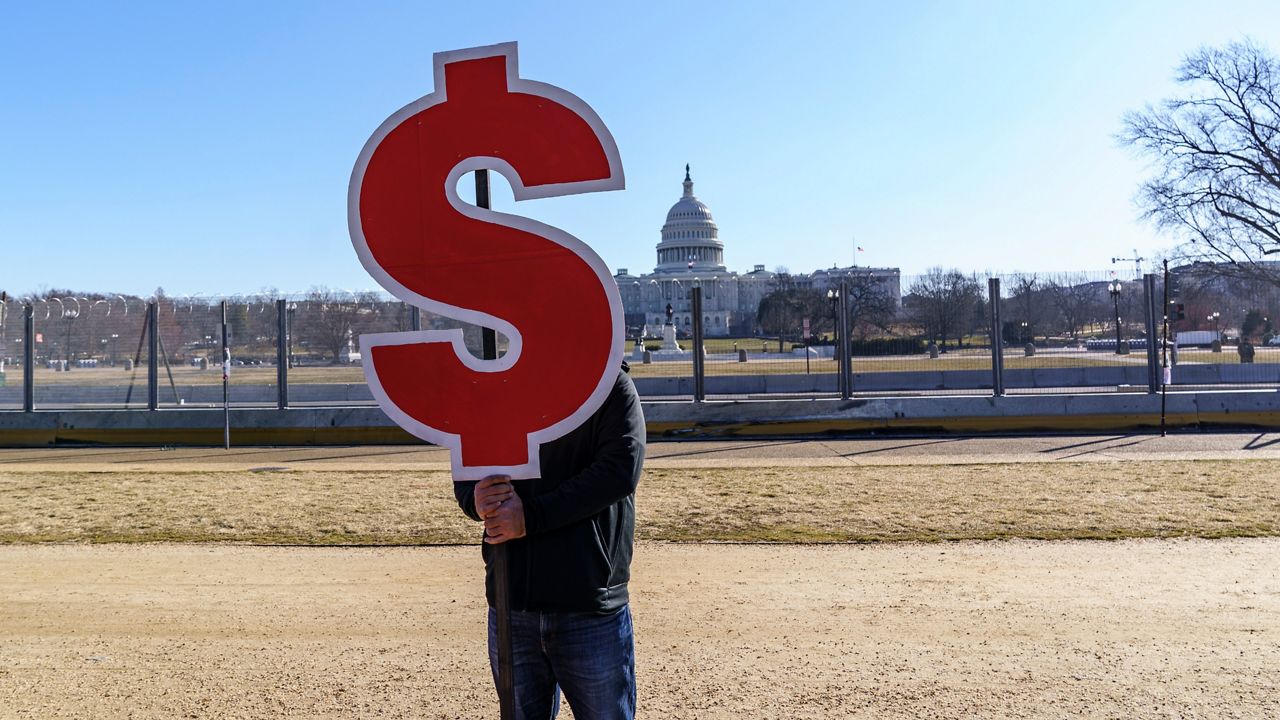

The fight for $15

While states can set their own minimum wages above the $7.25 federal minimum wage, the United States is in the middle of its longest stretch without a hike in the federal minimum wage since FDR first signed that bill. Some Democrats in Congress and Biden seek to more than double the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour in installments by 2025. The new wage would begin this year at $9.50 an hour. After 2025, under the proposed legislation, the minimum wage would rise based on an index tied to median wage growth.

Both sides turn to the economic and social consequences of COVID-19 to bolster their cases. Proponents say about a fifth of the workforce would get a raise, which would boost their annual pay, on average, more than $3,300.

That hike would particularly benefit Black and Latino workers, who make disproportionately less than others. In all, the legislation would lift 900,000 people out of poverty, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

“I take that as a pretty positive outcome – if you're going to be lifting nearly a million people out of poverty and raising pay for twenty seven million, even if there is some negative impact on jobs in some places,” David Cooper, a senior analyst at the Economic Policy Institute, said in an interview with Spectrum News.

Opponents counter that economic research shows no effect on alleviating poverty. Many of the least-skilled and least-experienced workers would be adversely affected if businesses were forced to raise prices or turn to automation to make the higher payroll. They also cite big cost-of-living differences across the country to argue against a uniform national hike.

They also note that the same study from the Congressional Budget Office finds higher wages would slash jobs for 1.4 million workers.

“The real minimum wage is zero, which is that people can lose their jobs. And unfortunately, when you hike the minimum wage, everyone acknowledges you do get job losses,” said Jarrett Skorup of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy.

What is fair?

Minimum wage arguments tend to devolve into dueling statistics. There’s a more fundamental, if highly subjective, question anchoring the debate: What is fair?

Monique Jamison and Tamra Kennedy share a history of poverty. But they give different answers to the same question.

Asked what is fair, Jamison, 32, answers “equal.”

“We should get treated the same as the high-paying jobs,” she says. “Treated the same way as these top dollar, rich companies. We step out here on this line, too. Don't look at us like we're bottom feeders.”

But Kennedy, 57, says: “It doesn't seem fair that the equity that you earned through hard work is devalued by making everybody even across the board."

She acknowledges the $7.75 an hour bump could be “life changing” for many workers — but notes her employees’ entry wages are already around $9.25 an hour; under her financial plans, she can’t afford to bring them to $15. What’s more, she says she would have to pay more in Social Security, Medicare, unemployment taxes and workers compensation insurance.

Then there is a risk far harder to quantify: the threat Kennedy sees to hard work, incentives, and learning workplace skills — “the biggest cultural problem we're going to have,” she calls it.

It’s steeped in her personal history. Kennedy pays herself $50,000 a year — less than all but one of her general managers, she says — with profits reinvested in her restaurants. But she started at the company she now owns as a secretary, earning $4.05 an hour. This after a childhood and early adulthood bouncing among relatives and cheap hotels.

“The parentals were not in a position, I guess, to raise us,” she says. “I'm fairly certain I can say that I went to 17 schools in 12 years.”

In the absence of her own steady formal education, Kennedy has morphed into something of a teacher to employees of what she considers traditional American workplace values. Her courses on how to serve tacos are framed with lessons in diligence and perseverance.

“My goal will always be that when you leave — and we hope that you do, unless you want to move up and become a GM [general manager] — that you'll know more than you ever did when you started and that you can use it on the next step in your work journey,” she says.

“I believe that if you work hard and you respect the value of work and you find an employer that respects that, then you will move up and you will change your life by doing it.”

Kennedy says if she were forced to pay her newest employees $15 an hour, she’d feel obliged to bump up salaries of more veteran workers — and those willing to work during unpopular hours. It would rattle the workplace equilibrium, undermining the lessons.

“You literally have disincentivized so many people that have already been in the workforce,” she says. “Because now they're being made to feel that those efforts were not worth it. There's a huge internal morale conflict that we're starting to sense and feel in our restaurants.”

She could trim costs; you may have seen self-ordering iPads, say, at airport restaurants.

“I think it's better to invest in people and in communities and give people a chance to learn,” she says.

In all, it means something has to give if everyone were to make at least $15.

Asked “what is fair?” Kennedy has a retorting question: “How much are you willing to pay for a taco?

The people behind the paycheck

Monique Jamison had dreams. First, it was to be a doctor. Then, a singer. Actress. Scientific investigator, like the kind she watched on “CSI.”

There are pauses, and her eyes seem to well as she runs through what she hoped, and what she said happened instead.

Dropping out of high school; homelessness; having one daughter taken by family services; another living with her godmother. Her job, serving chicken fingers at Raising Cane’s..

“I was dumb when I was young; when I got older, I got wiser,” she says.

Now, Jamison has another dream: a trip to see the lights of Las Vegas.

“I really want to try to go places, but it's like money-wise — too tight. I can't move. I feel claustrophobic because I got bills. I don't have the money to have fun, basically.”

“Yes, I did some off-the-wall things that I shouldn't have done, you know, and I regret it,” she says.

“Then, I look at it's a lesson learned. I wouldn't be where I'm at today, I wouldn't be doing what I'm doing now if it wasn't for those certain trials and tribulations in my life.”

When she talks about now, Jamison’s face brightens.

Not long ago, a friend clued her in on Missouri’s “Show Me $15” campaign — Missouri’s segment of a national bid for fast food workers to unionize and earn at least $15 an hour.

She learned about corporate profits. She gave interviews.

She learned of others who couldn’t pay the bills.

“I'm not only yelling for myself, I'm yelling for these families out here, these working mothers, these working fathers, the single fathers."

“It's not only single mothers out there, it's single fathers out there ... making this wage that's not dependable on to try to live ... to just live life."

While opponents to the minimum wage say a significant number of workers earning the minimum wage are young people who aren't fully supporting themselves, according to the Congressional Research Service, those aged 16-19 account for 17% of those earning minimum wage or less; those aged 25 and higher account for about 57%.

Jamison says she’s tried to climb the corporate ladder — but can’t. Jamison says she’s tried to climb the corporate ladder — but can’t.

“They feel like you [are] not qualified because you have fast food experience. Or it's not enough experience for them,” she said.

“They don't actually step in our shoes and see what our life is with this check that we’re making every two weeks just to pay bills or just to even get by. They don't know what our day to day life is after our 8 hours. They don’t know what we go through.”

Raising Cane’s, a privately-owned company headquartered in Louisiana with more than 500 locations, reportedly made $1.18 billion in sales in 2019. Its founder and CEO, Todd Graves, was recently profiled for forgoing his salary during the early days of the pandemic to avoid layoffs.

A spokesperson didn’t return a message for comment.

Jamison calls the campaign for the $15 minimum wage “my stepping stone to start to change the world.”

“That was one of my things and one of my goals I wanted to do because I feel like the world was being bullied.”

Today's minimum wage politics

On stage at the Pabst Theater in Milwaukee one February night, President Joe Biden looked out at the audience at the president of an 89-year-old Wisconsin woodworking firm.

It was a town hall, and Randy Lange told the president that business owners were concerned about the minimmwage.

We're at $7.25 an hour,” Biden responded. “No one should work 40 hours a week and live in poverty. No one should work 40 hours a week and live in poverty.”

The audience applauded — but noting business owners’ worries, Biden also called it “a debatable issue.” And since then, he’s reportedly sounding less convinced there’s enough support in Congress for a $15/hour bill, even as, officially, the White House is pressing on.

Democrats’ best chance may have been dashed with a February ruling from the Senate parliamentarian that stripped the hike from the stimulus bill that passed the House of Representatives. The final $1.9 trillion bill that Biden signed left out the minimum wage hike.

Debate now moves to a stand-alone $15/hour bill, the Raise the Wage Act, introduced in the U.S. Senate by Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont in January. Two Republican U.S. Senators, Mitt Romney (R-Utah) and Tom Cotton (R-Ark.), are pushing a rival bill that would raise the minimum wage to $10/hour, with measures to crack down on undocumeted immigrants in the worforce.