FORT WORTH, Texas — Dave Mayer remembers Gov. Greg Abbott’s press conference almost exactly one year ago. He was bartending at local barbecue mecca, Heim Barbecue. He and a few regulars watched on the restaurant’s television as the governor spoke of a short-lived shutdown until hospitals could “flatten the curve” in dealing with COVID-19 patients. Mayer hasn’t worked since, though lately, that’s been by choice. He’s choosing to wait to return to work until after he’s inoculated.

If you’ve ever sat at his bar, Mayer probably remembers what you drink. Depending on your order and how busy he is, your beverage of choice will likely be waiting for you on the bar-top long before you’ve finished saying hello to friends and find a seat. Mayer isn’t some kid working his way through school — he’s a professional, and, if you ask any of his regulars or co-workers, a savant. The veteran bartender has worked behind “the stick” at an upscale cocktail lounge, a beloved dive, and more.

Mayer, affectionately known as “Tiki Dave” for his signature elaborate Pacific island concoctions, is one of the millions of service professionals whose life changed suddenly and dramatically when COVID-19 paralyzed the industry. Like every restaurant in the state, Heim closed its doors to dine-in guests for a time. Mayer’s other gig, a nearby bar, The Chat Room, closed its doors the following day.

“I’ve been fortunate,” he said. “I've got to say, unemployment has held out. It has not been what I was accustomed to making by any stretch, but it was definitely enough to keep the lights on and groceries in the pantry. My girlfriend moved in with me because I wasn't mixing with anybody. I couldn't have felt safe if she'd still been going out to work and such. She came in and hunkered down in my house, and we've just been pretty much locked in for a year.”

Mayer’s story is a familiar one around the state and country. The food and beverage industry accounted for one in four jobs lost during the pandemic — more than any other sector of the economy. Without additional assistance, tens of thousands of bars and restaurants have shuttered, taking millions of jobs with them.

According to The National Restaurant Association’s 2021 State of the Restaurant Industry report, the restaurant industry took a $240 billion hit, compared to last year’s numbers. As of December (as far back as the nonprofit’s data goes) more than 110,000 eating and drinking establishments were shuttered. The service industry finished 2020 nearly 2.5 million jobs below its pre-Coronavirus level. At the peak of initial closures, the Association estimates up to 8 million employees were laid off or furloughed.

In Texas, where restaurants account for roughly 51% of food dollars spent, the pandemic hit harder than most states. Data from the Texas arm of the National Association found that 167,000 service industry employees were still out of work as of February (that’s down from 350,000 during the weeks of the stay-at-home order), and more than 11,000 restaurants (between 20 and 25% total) have permanently closed.

With yo-yoing regulatory limits on how many people a restaurant or bar could allow in, the service sector has been slow to recover. A study conducted in February by the Texas Restaurant Association that surveyed 3,000 restaurant operators found that the workers within that sector believe that the industry as a whole is still nose-diving and won’t bounce back for at least 7-12 months.

According to TRA data, 81% of operators in Texas say sales were lower in January 2021 versus January 2020; 40% of Texas operators thought their sales would decline from January's levels; and 85% of Texas operators expect their staffing levels to be lower than it was in January.

The free-fall of the hospitality sector doesn’t just affect workers like Mayer. Plummeting restaurant and bar sales also impact the entire supply chain. Industries such as agriculture, trucking, and others are feeling the pinch, as the virus has disrupted the symbiosis between them.

As people waited out the pandemic at home, demand for meat decreased and prices dropped. As a result, livestock supply will become tighter in the long run, most observers believe. Produce, which is highly perishable, also had to be thrown out when restaurants began to close — forcing farmers to reconsider how many crops they produce this upcoming season.

Only this week has the pandemic loosened its grip on the wallets of bartenders, cooks, waiters, bussers, and most of the millions of people who work in the field. Though many believe it’s premature, Gov. Abbott lifted restrictions on the number of people bars and restaurants can host. Experts agree his orders will almost certainly take a toll on public health, but many Texas business owners celebrated the move.

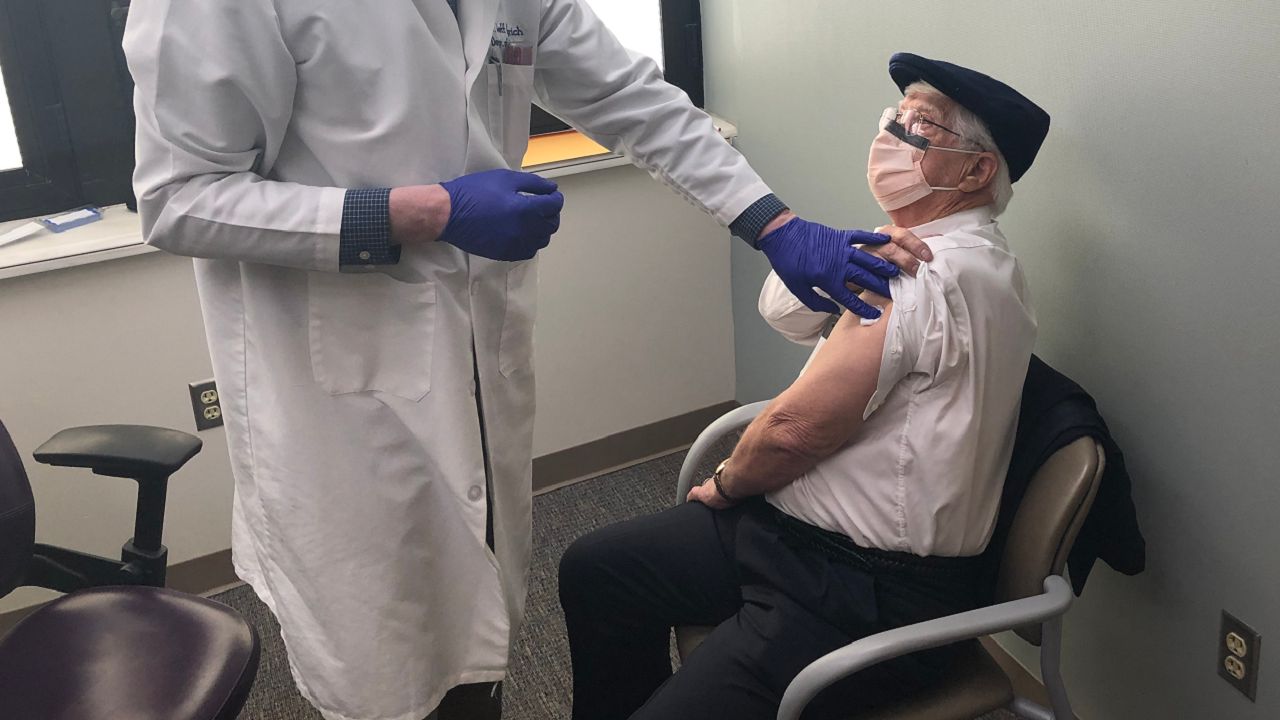

Mayer will receive his second shot of the Pfizer vaccine in a couple of weeks. After that, he said, he’ll be pounding the pavement looking for work.

“I'm a dyed-in-the wool bartender,” he said. “I've done sales. I've done lots of things in my 36 years on this Earth. But I've been waiting to get back to the industry.”

When COVID-19 became a reality in Texas last March, the service industry was the first to bear the brunt. Prior to the pandemic, there were over 1.1 million Texas jobs in that industry. By the end of April 2020, when Texas was under a statewide stay-at-home order and businesses were shuttered, the sector had shed 40.3% of jobs, according to data from the Texas Workforce Commission.

Of the 3.2 million unemployment claims filed in Texas between the beginning of March and the week ending Aug. 8, around 12.5% came from workers in the food service industry — the largest share for any single industry in the state, according to a Texas Tribune analysis of TWC and U.S. Employment and Training Administration data.

One frightening trend for many observers is the loss of independently-owned restaurants. One year ago, there were roughly 500,000 eateries in the state. A quarter of them are gone.

“Overwhelmingly, independent restaurants have been hit by this,” said Anna Tauzin, the chief revenue & innovation officer for the Texas Restaurant Association. “It's usually your smaller operations, with people that maybe didn't have the kind of savings in the bank to weather the storm.”

Many like Mayer wonder if the character of local dining scenes will buck and reel under the encroaching threat of corporate hegemony. He said he’s not sure if he could work for a place that requires him to wear flair at this point in his career.

“The biggest thing I'm concerned about is the shift of small businesses that can no longer afford to get back in the game,” he said. “I don’t want to see everything turn into a Chili's now because Brinker is the only company with money left.”

Tauzin said while the TRA is devastated by the vanishing act of the many indie restaurants over the past year, she believes that Texans won’t support a chain-dominated landscape.

“Texans really do love their independent restaurants,” she said. “So while we mourn the loss of independents, we know that other independents are going to take their place. There will always be an independent character for Texas restaurants no matter what happens.

“As much as we appreciate large national chains having presence in our communities — they hire locally, they give back locally — we do not want to see a world where it's just chain restaurants, either,” she continued. “Independent restaurants will always make up the character of the state, and I have full confidence that those that have held on will make it, and there will be more coming in, too.”

While countless discussions about how the state handled the COVID-19 crisis clutter social media feeds around the country, Tauzin said the governor made two key decisions that allowed some restaurants to survive. He signed two waivers: one allowing eateries with a liquor license to sell to-go mixed drinks, and another that let restaurants act as grocers.

“We know that there was a run on grocery stores early on in the pandemic when people couldn't get the supplies that they normally could,” she said. “But the distributors that supply restaurants were still able to get products in their hands. And so restaurants were then able to sell unprepared food, like bulk produce, bulk meats, even paper products, and flour. I remember at the beginning of the pandemic, everyone was baking all the time.”

The TRA has authored two bills for consideration this legislative session that they hope will make these two pivots (Tauzin prefers the word “jukes”) permanent. The bill allowing restaurants to sell groceries has support but has yet to be filed.

The alcohol to-go bill made it through committee Wednesday and will likely move forward to an up-and-down vote.

“Every branch of alcohol business in the state of Texas is in support of this, which never happens,” she said.

Another “juke” she said will likely become permanent is curbside pickup. The restaurants that quickly adjusted to that model tended to fare better than those that didn’t.

Jon Bonnell, owner and executive chef of three popular Fort Worth restaurants, has had mixed results with curbside, he said. His flagship steakhouse, Bonnell’s Fine Texas Cuisine, regularly sells out its curbside offerings, with lines of cars wrapped around the corner. Patrons of his downtown seafood restaurants, Jon Bonnell’s Waters: Fine Coastal Cuisine, haven’t embraced the curbside trend as much.

Curbside at Bonnell’s, he said, is here to stay — as long as there is a demand for it.

“Curbside has not tailed off at all since the announcement from the governor last week,” he said. “My opinion is as long as people still like it, we're going to keep it up for the indefinite future. So it may be one of those parts of COVID that just sticks. Plenty of people that are still nervous about going out to eat, and I completely understand why. If they would rather come drive through, we will keep it open.”

Another “juke” he said will likely become permanent is a new online ordering system he implemented at his three restaurants. Other changes he’s keeping, at least temporarily, include Plexiglas between tables, and the many safety precautions his staff has taken all year.

“We're just kind of slowly coming out of it with a few more bar stools, a couple more tables here and there — working our way back to normal on a slow, sustained basis rather than just trying to turn it on,” he said.

In the near future, many restaurants are still requiring guests to wear masks when they’re not seated. Tauzin said a TRA poll of restaurant operators revealed that 38% were not going to require masks, 42% were going to require, and then another 20% said they were unsure.

“When you talk to people that are in that unsure category, the reality is they want their guests to wear masks. But are they going to create a scene or ask them to leave? Maybe not. Some definitely will, and they'll make a big deal out of it. Some people will just go ahead and seat them and take their money because they need to survive.

“Restaurants are well-equipped to handle these kinds of confrontations,” she continued. “It's just such a shame to see a group of people who use the words ‘personal responsibility,’ and when a business has decided what is best for them, their business, and their teams, for people to suddenly say, ‘Oh, well, it's actually not your decision. It's mine.’ That feels really hypocritical.”

Bonnell said one lasting impact of the pandemic, at least in Fort Worth, has been the positivity between independent restaurant owners and operators.

“I've never felt a better sense of community in the Fort Worth independent restaurant scene,” he said. “All of the restaurant owners, chefs, and managers have worked together rather than as competitors. To see the scene where somebody says, ‘Hey, by the way, there's a new city grant that we're all eligible for. Let's all work together on this’ instead of ‘that's mine.’ ”

“The entire independent restaurant scene has really come together as a brotherhood and sisterhood to work together to get through,” he continued. “This has been inspiring. And I don't think that'll go anywhere.”