CASTAIC, Calif. — With a name like Trevor Waters, it seems like this valley resident was destined to spend time out on a lake.

“You know what they say. A bad day of fishing is better than a good day at work,” he said, with a smile to prove it.

Waters' boat is one of the up to 50 thousand to launch on Castaic Lake every year and while he doesn’t mind sharing the facility, he also makes sure to do his part to protect it and that starts with his vessel.

“Whenever I go home I always rinse it with fresh water,” he explained. He does this to remove any remnants of potentially infected lake water from his engine, “because if you transport it to somewhere that’s clean, it’s no longer clean.”

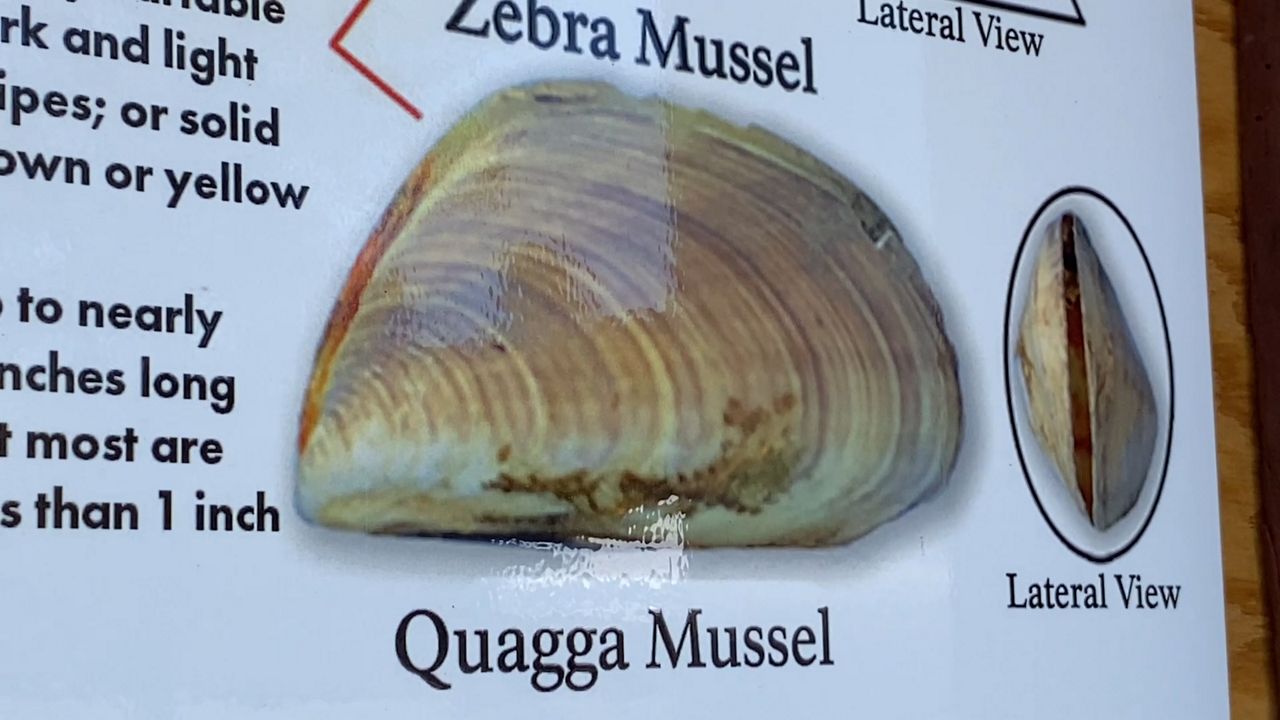

He’s talking about the spread of quagga mussels – a very small, non-native species first discovered in California in 2007. Last month was the first time they’d been spotted in Castaic Lake.

Tanya Veldhuizen works with the Department of Water Resources and specializes in invasive species.

“This is one of those cases as a biologist where we hope to never see our study animal,” she said.

The first quagga in Castaic Lake was found by park visitor. It was dead but she says mostly likely had been recently alive. Over the next three weeks, DWR and California Department of Fish and Wildlife staff found decayed shells of three more dead quagga mussels along the shoreline.

The discovery is problematic for a number of reasons. Castaic is a drinking water reservoir equipped with pumping machinery, pipelines and grates to catch debris.

“These mussels can form basically a crust several inches thick and completely cover structures,” Veldhuizen explained.

They also pose an ecological hazard, feeding on good algae and excreting blue green algae.

“That can cause a harmful algal bloom,” she said. “They can produce toxins that are harmful to people and pets.”

If the population balloons it can be problematic. Right now it doesn’t seem as if they are reproducing. Christopher Mowry is a superintendent at the lake. He says the initial discovery was “a bad day” but one they’d been preparing for.

DWR conducts regular monitoring, even before these findings, and has continued conducting them since. So far, no evidence has been found of the mussels in their larval stages, which Mowry describes as “free floating in the water column, unseen to the naked eye."

“So that’s why it’s just all about the water and being transported in the water,” he explained.

While they never wanted this unwelcome visitor, his team did have a plan in place to deal with it. They regularly inspect boats coming in to make sure they are dry since any water could potentially be carrying stowaways. Now they’ve added another inspection on the way out, making sure the boats are on their way to being dry, which will help prevent any further spread. They also add the boats to a database other facilities can check and they mark the vessels with a tag.

“A physical notification that the boat’s been on infested waters,” he said.

The exit inspection might take an extra 15 minutes, and Mowry also uses that time to educate boaters about what they are doing and why.

As for Waters, he doesn’t mind the extra step or the extra wait.

“If that’s what it takes to keep this place open,” he said, “and keep us coming out here and fishing and having a good time, then I’ll do it.”