If any one phrase has taken over the English speaking world over the last 12 months, it’s “the new normal,” a verbal shrug and hand wave at how the world has changed in this modern pandemic. The very suggestion of a new normal implies that the world is simply a more challenging place to live.

But the Beverly Hills High School yearbook staff saw an opportunity for a bit of fun. Their school’s mascot is inspired, in part, by William the Conquerer, the first Norman King of England. The yearbook’s theme this year?

The New Normans.

“It’s a great way to explore what the heck is happening with life right now. What does it mean to be a Norman right now? What does school look like for us?” said Aasha Sendhil, a senior at Beverly Hills High School and editor of The Watchtower yearbook.

What You Need To Know

- Students across the Southland are struggling to put together yearbooks, their local records of the school year amid the pandemic

- Yearbook staffs have altered plans, replacing standard sections like athletics and clubs with feature stories about students and COVID-19

- Some high school yearbook advisers are worried that they may not reach necessary sales targets, which may lead schools to rethink publishing yearbooks

- Students are still aware of the importance of yearbooks, acknowledging them as historical records of their communities

At their best, school yearbooks are an annual touchstone for their community. They’re a record of student achievements and activities and a time capsule of student life and fashions. They’re a resource shared with libraries and police departments, and an archival document often pulled up when looking back at the lives of people in the public sphere.

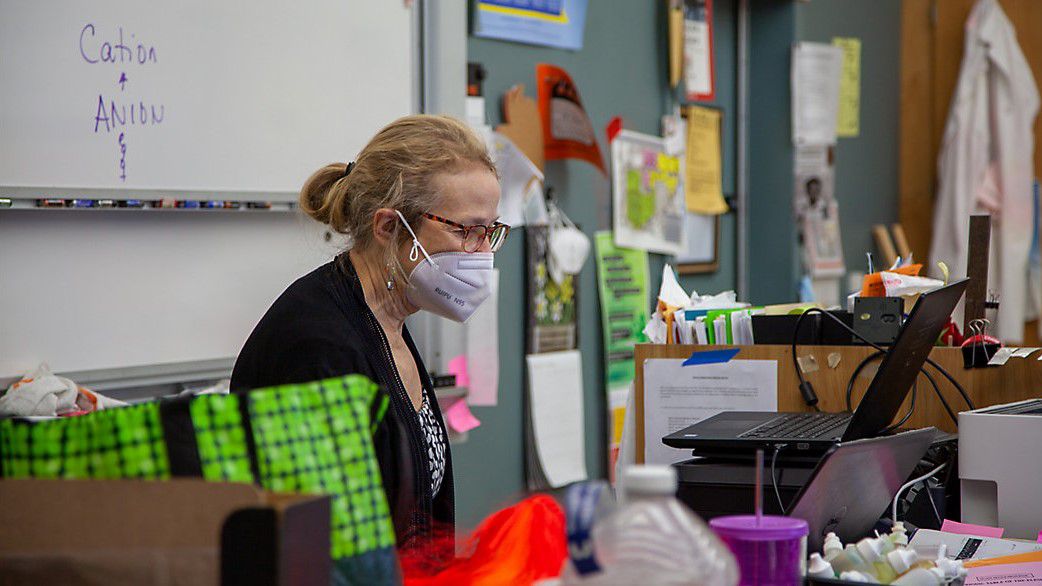

The pandemic has wholly upended the production process for student publications. Typically, yearbook and newspaper staffs would be documenting student life, running all over campus, taking photos, interviewing students and faculty.

But with campuses closed and classes running remotely, yearbook staff have had to adapt. Sendhil even built a short slideshow to teach students and teachers how to take their best possible portrait photos from home.

“Photos are the backbone of the yearbook. But they can’t be right now, because what is there to take a picture of? How many photos can you have of a kid sitting in front of a computer?” said Beverly Hills High School yearbook advisor Gaby Doyle.

And so The Watchtower this year is more like a magazine, filled with articles and surveys and infographics. Sendhil said that this year’s book has multi-page spreads about the 2020 election and data-driven spreads on the COVID pandemic facts. But it also has a pop culture in 2020 spread.

“It’s still a time capsule. We want to look at what songs are the most popular, or what slang us teenagers still use,” Sendhil said. “We’re trying to have fun with it,” she added, though she admitted that “it’s hard to find fun in anything these days when you’re home alone.”

Daniel Pearl Magnet High School newspaper and yearbook adviser Adriana Chavira said that the biggest challenge has been ensuring that her students have remained persistent.

“It’s difficult for them to conduct interviews because they sometimes don’t know how to get a hold of students or teachers,” Chavira said. “So they have to be persistent, to keep sending emails to them…it’s a bit harder, and we’re probably not doing as much as we would if we were in person, but I think they’re doing a pretty good job.”

At Redondo Union High School, yearbook and newspaper adviser Mitch Ziegler — who was just named the 2020 H.L. Hall National Yearbook Adviser of the Year by the Journalism Education Association — says that he and his student staff have found ways to adapt despite the challenges of the pandemic.

“When you think about it, we have no sports, we have no classroom shots, we don’t have a single activity, no meeting of student clubs. That’s four sections of the book we don’t have anymore,” Ziegler said.

So he and his students have gotten creative. This year, Ziegler’s photo class students created what he called “gratitude photos,” showcasing what they’ve been thankful for during the pandemic. That, he figures, should produce a substantial spread for this year’s book — but they’re still hustling for content.

“We have put out a help call to the parents: if your kids are doing anything, if you or they can take photos of it while it’s happening, send them,” Ziegler said. The key there, though, is “while it’s happening.”

“The parents are…the parents are just bad at it,” Ziegler said, laughing.

One of the biggest concerns for yearbook programs is whether they’ll be able to sell enough yearbooks. Redondo doesn’t expect to have a problem. Sales at Beverly Hills have fallen, but the program is working to make sure that they meet targets. Doyle even got permission to sell yearbooks at the school’s diploma pickup site. But Pearl is a relatively small school in Lake Balboa, with only about 250 students.

“For our school, the goal is to sell 100 books. Usually, by now, we have more than half of them pre-sold,” Chavira said. That’s not the case this year.

Like nearly all schools, Pearl has a contract for sales with a yearbook production company — in this case, Walsworth, though companies like Jostens, Balfour, and Herff Jones are among the other major players in the high school yearbook market.

“We signed contracts the year before (the pandemic), and it’s hard for us to cancel those,” Chavira said.

According to Kristin Mateski, a spokesperson for Walsworth, the publisher has seen a general increase in sales this year and a 5 percent increase in its California schools.

“We help schools in ways that help facilitate sales, mostly email marketing and social media marketing tools,” Mateski said. Some schools have used coupon codes and sales competitions to try and drive sales as well.

Walsworth has also developed apps that can help students and parents submit photos directly to their yearbook staff, which Mateski called an important engagement tool.

“Students in yearbook are used to using whatever tools they have to create the product, or the story,” Mateski said.

But Chavira wonders how the pandemic might have shifted the future of the yearbook, especially if sales continue to decline.

“I haven’t had this discussion with our principal, but will this mean that we’re not going to have a yearbook next year, because how are we going to get out of this? Is there any interest in students get a yearbook anymore?” Chavira said.

The argument she’s heard is that social media has taken over the yearbook’s function.

“But in 20 years, will that social media still be around? The book, people have that forever… they reflect what’s going on now, and they’re a good reminder 20 or 30 years from now of what people went through,” Chavira said.

That she’s overseeing a historical document isn’t lost on Sendhil. Her staff, she said, has learned so many skills to carry them through this year.

“It’s about building confidence in them,” Sendhil said, “that even with these challenges, they’re able to represent the community and make a time capsule for everyone to remember, even though we’re not physically connected.”