As heatwaves bake the Southwest and agricultural workers brave the sweltering temperatures, often risking their health and lives, some are calling on the government to issue a federal heat rule to protect workers.

Jose Ramirez Duarte started working in the fields of Coachella Valley almost 40 years ago. The area is largely desert, with temperatures regularly reaching more than 110 degrees in the summer. So, Ramirez Duarte knows the dangers of heat firsthand.

“The difficulties of being in the heat is that you can get heatstroke if you work like it is today,” Ramirez Duarte said. “Right now it’s 106. It was 117 a few days ago.”

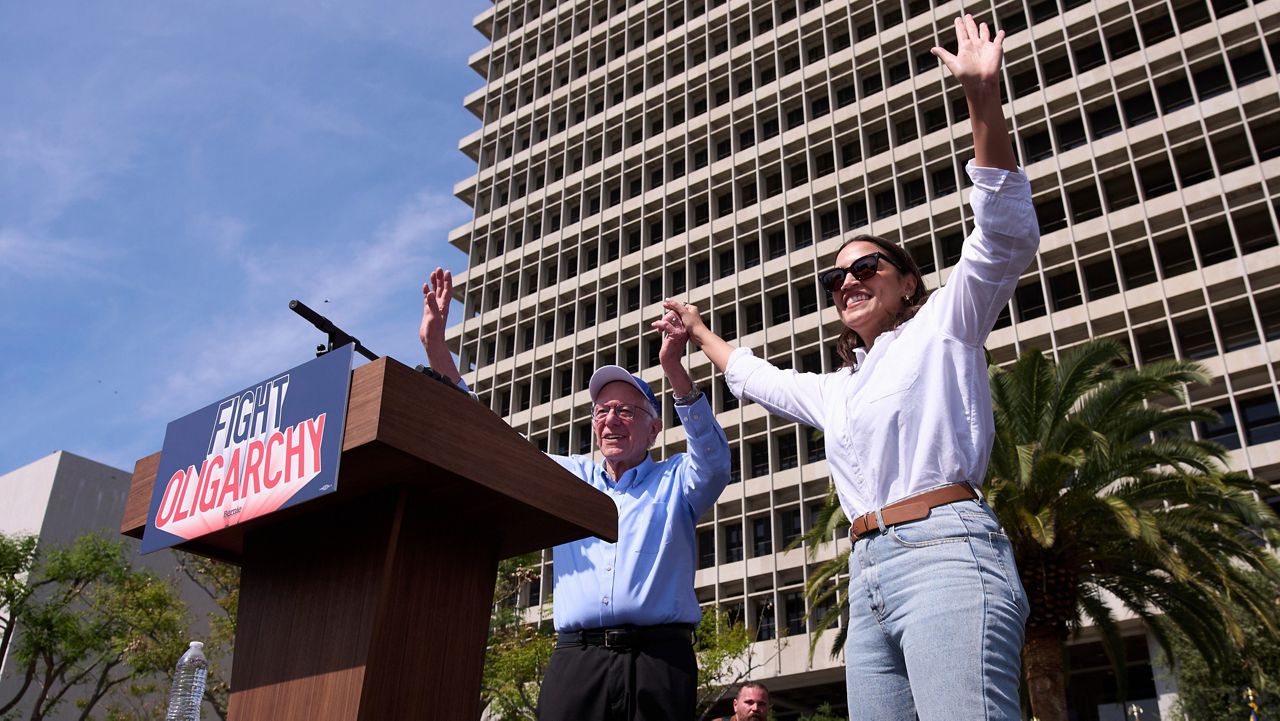

Ramirez Duarte works for United Farm Workers, a union co-founded by the late labor leader Cesar Chavez. In the wake of two farmworker deaths in Arizona and Florida, UFW is calling on OSHA to issue a federal heat rule protecting outdoor workers like Ramirez Duarte.

Antonio De Loera-Brust is the communications director for UFW and he said the federal government needs to act now.

“We really need OSHA to issue nationwide safety rules as fast as possible,” De Loera-Brust said. “Delay is not just measured in time, it is measured in worker lives.”

The Biden administration initiated a rule-making procedure in 2021, but two years later, still no standard has been set.

De Loera-Brust also said the economic pressures many farmworkers face contribute to the dangers brought on by increasingly harsh weather.

“The desperate poverty many farmworkers live in is a huge contributing factor here,” De Loera-Brust said. “The fact that the workers who feed America can barely feed themselves, is part of the problem. Farmworkers feel pressure to work harder, work faster and get as much money as they possibly can for their families, but that economic pressure is counter to their own health and safety.”

Hilario Torres worked on fields near Coachella for more than 4 decades until becoming disabled in 2007 and he remembers just how dire economic conditions were for many workers when he first got started.

“I remember before 1975, almost no farmworker had their own house because they didn’t have enough money,” Torres said.

Torres remembers working 13 hour days and watching a coworker die in the heat. He still lives in the area and actively organizes with UFW to advocate for stricter farmworker protections. Since his early days in the fields, Torres said UFW has been able to secure better working conditions and compensation for farmworkers and he credits Cesar Chavez, whom he knew personally for many years, for leading that charge.

“Fortunately, we had a great leader who fought for many benefits,” Torres said.

And though progress has been made, Torres said farmworkers today face new challenges. As climate change increases temperatures in many agricultural centers like Central and Southern California, farmworkers have to contend with worsening heat.

“Every day, I feel it more. I don’t know if it’s my age, but I do think the climate is changing. Where it wasn’t hot, it’s hot now and where it was hot, it’s much hotter,” Torres said. “It is incredibly dangerous for workers.”

Last week, the Biden administration directed the Department of Labor to issue a hazard alert for some workplaces including farms and ramp up enforcement of heat related violations. While some advocates praised the announcement, others underscored the importance of fulfilling UFW’s call for a federal heat rule.

Because OSHA has not yet issued a country-wide mandate, state-level labor departments are responsible for issuing their own. California has among the strictest protections of any state, mandating workers be provided a quart of water every hour and shade to cool down in. Foremen like David Duarte, who oversee workers like Ramirez Duarte, say they do what they can to keep their workers safe.

“Here with me, fortunately, nobody has had problems with heatstroke or anything else,” Duarte said.

But according to Duarte, even though he said he keeps his workers safe, he agrees with calls for more protections.

Union farmworkers are proud of the protections they have been able to secure through decades of advocacy, but they say much more is needed. As for Ramirez Duarte, he said he loves his job, and plans to do it for as long as his body lets him, but his longevity may depend on staying cool while temperatures continue to increase.