Most people think La Niña means below-average rain and snow for California. This isn't always the case; in fact, some La Niña patterns are associated with average or above-average rain in parts of California. So how did the 2021-2022 La Niña pan out?

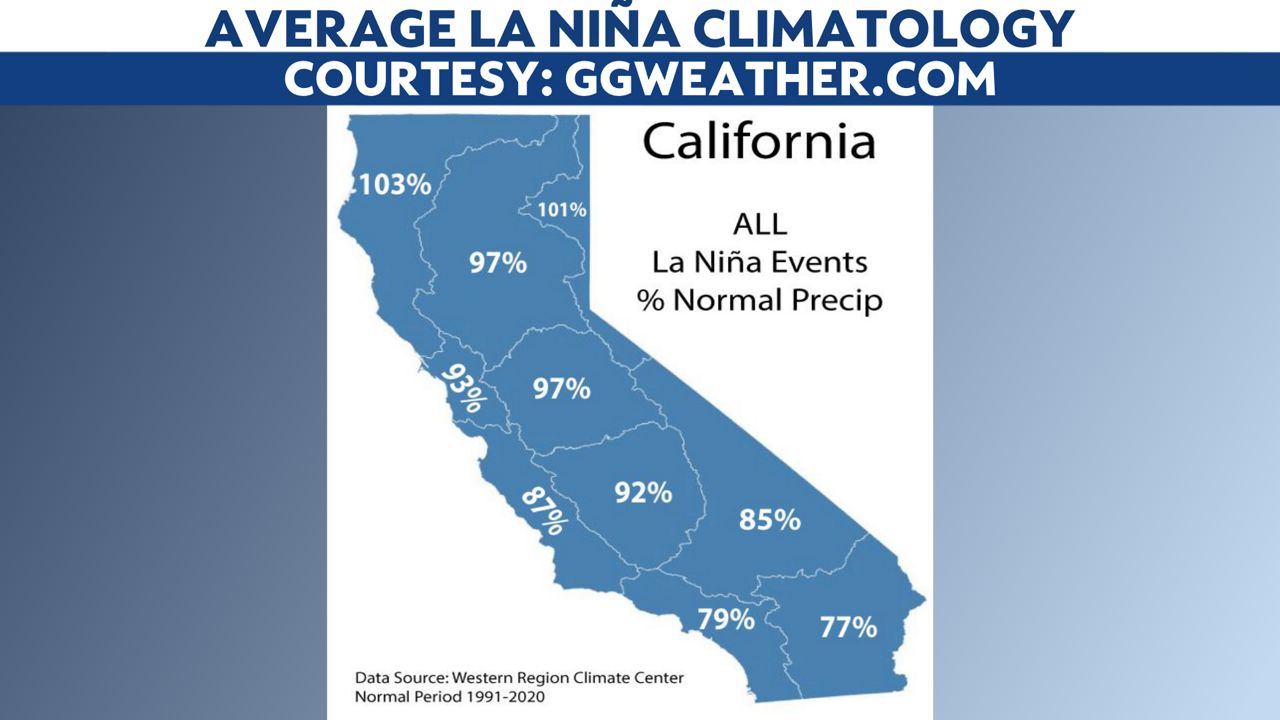

First, let's talk about La Niña climatology. Not all La Niña patterns are the same. Some are stronger than others and the strength of each one brings a different outcome historically.

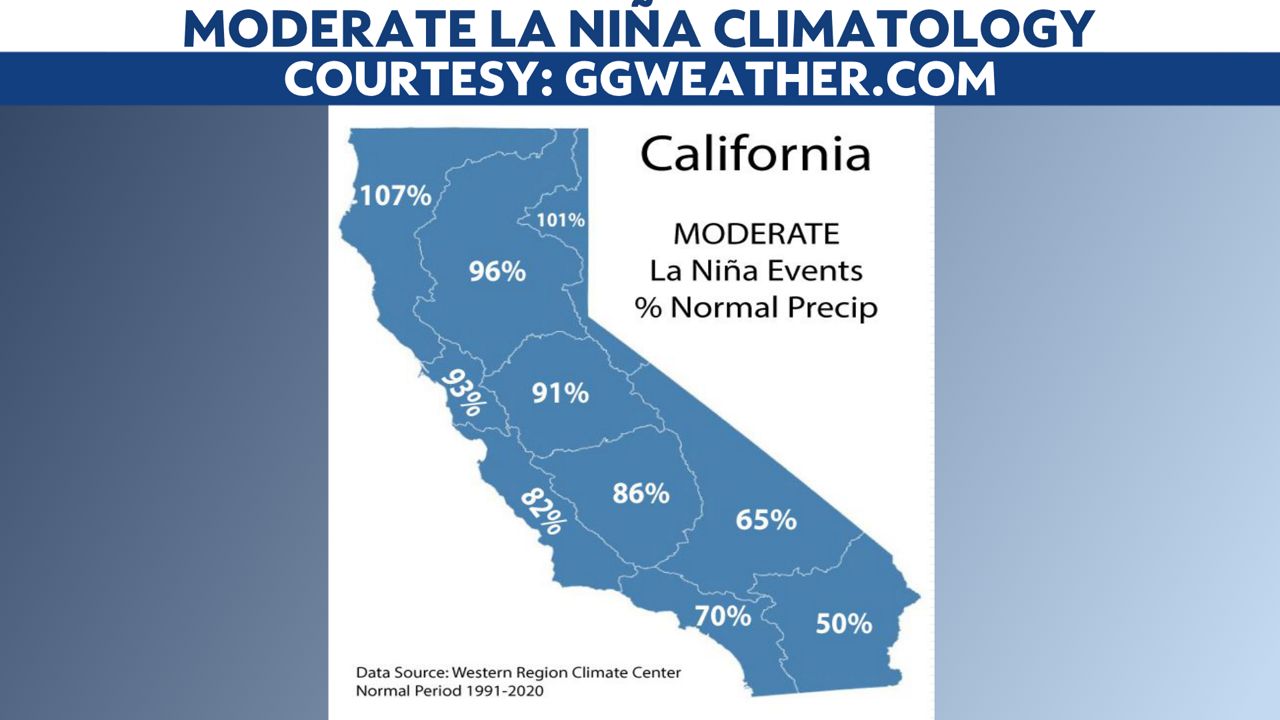

La Niña can be weak, moderate, or strong. Typically, a moderate La Niña leads to the driest conditions, particularly for the southern part of the state. Northern regions are largely unaffected by La Niña patterns, with near-average or even above-average precipiation across all patterns.

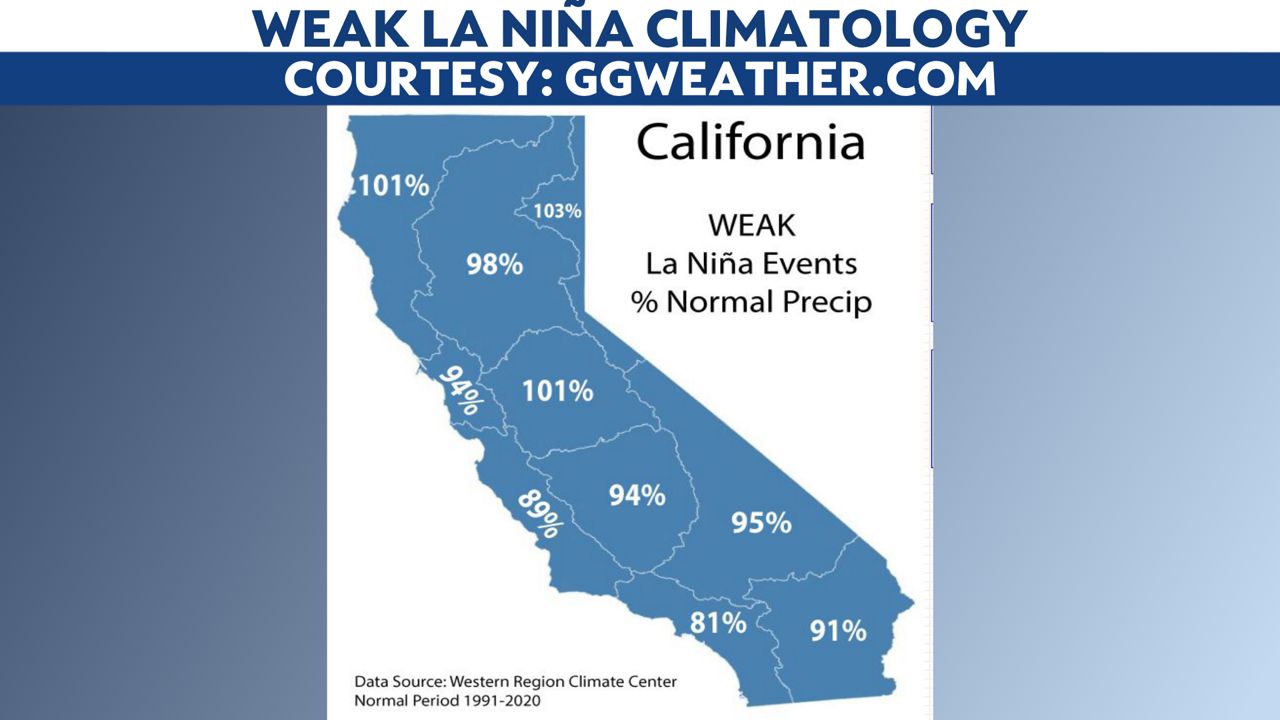

Weak La Niña events tend not to cause too much of a difference in seasonal precipitation averages, except in the Los Angeles and Central Coast regions.

A moderate La Niña packs a bigger punch, especially farther south and east. The 2021-2022 season was a moderate event.

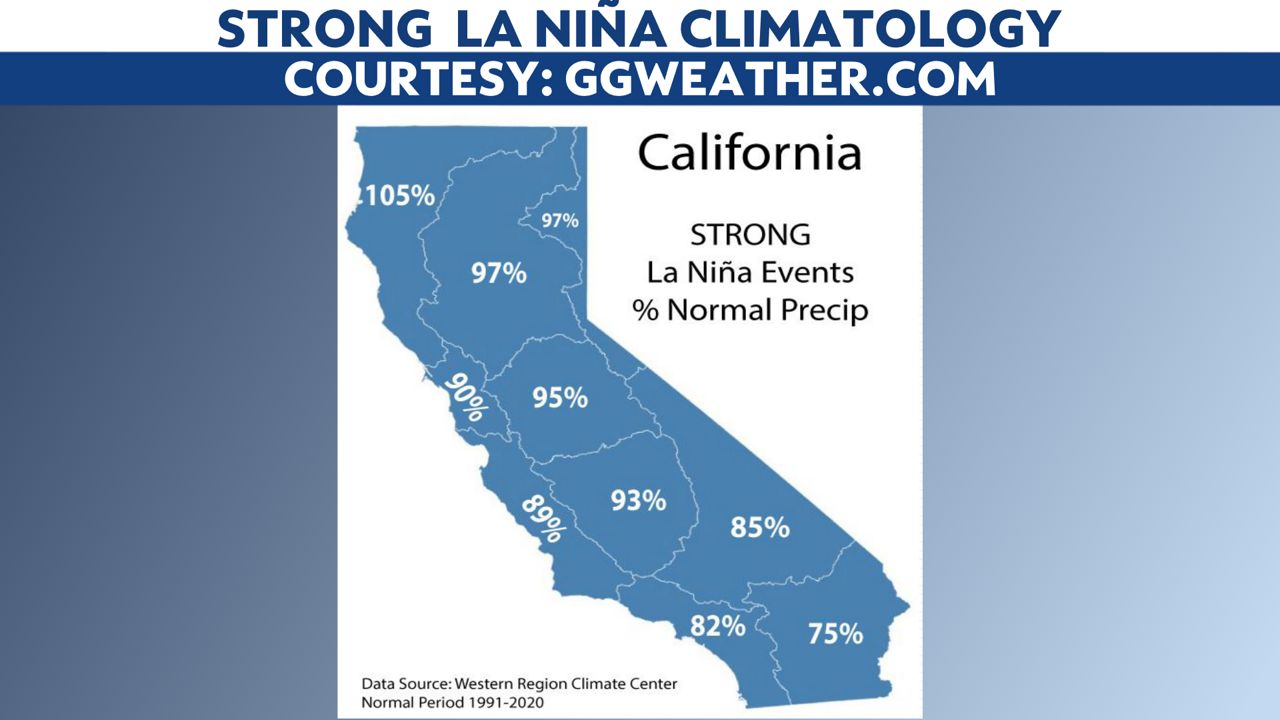

Strong La Niña patterns still typically bring below-average precipiation to Southern California, but it's not dismal. Northern California averages are still close to normal, including the ever-important Northern Sierra station index.

Again, it was a moderate La Niña year, but even that wasn't an indicator of how dry the season would end up.

It started off promising, especially after the Sierra saw record snowfall in December. Precipitation totals were up four to five times the monthly average for some.

Recall, California is part of the Mediterranean Climate, where most of the rain and snow in the state falls between November and March. Since it’s now May, the numbers are pretty much set—and it's dismal.

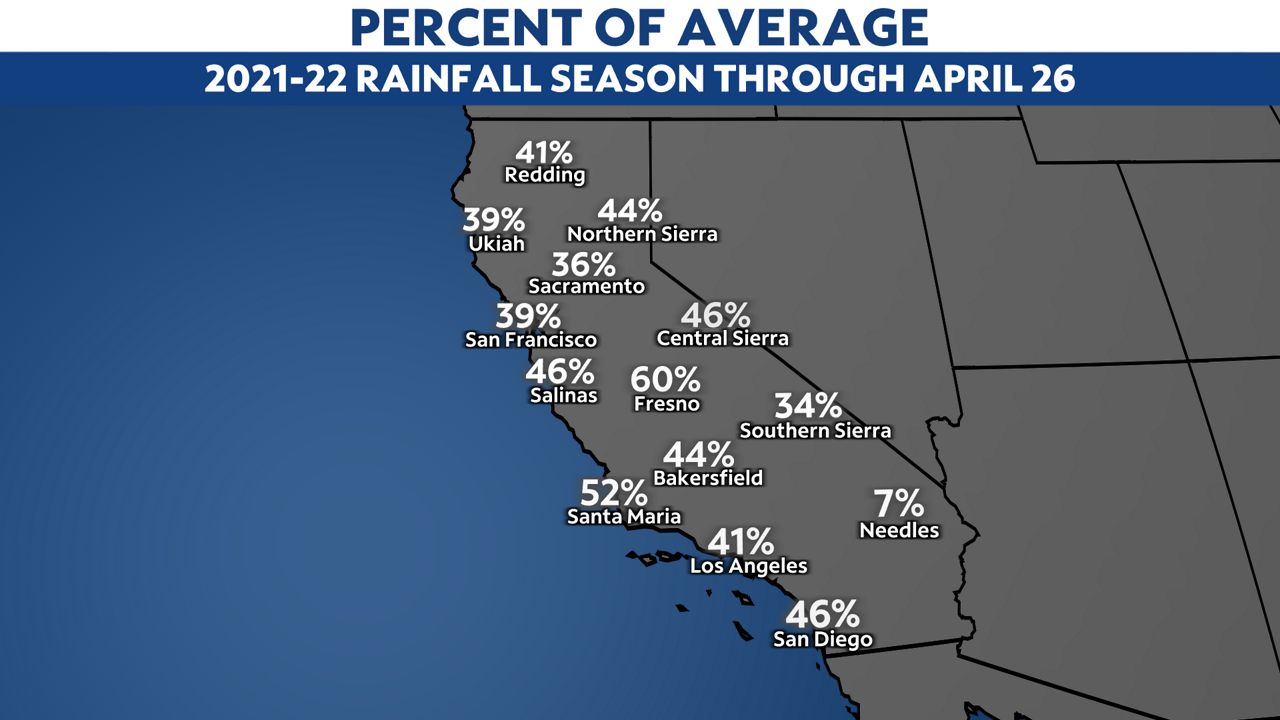

Totals ranging from 36 to 44% of average for much of the state falls well below La Niña climatology.

There are incredible deficits, especially in Northern California, where some places are now a full year's worth behind in precipitation.

It is particularly alarming in the Sierra. The season started on a promising note, with record snow falling at Donner Pass in the Northern Sierra in December. From January on, it was devastatingly dry, and there is now a 14-inch deficit in the water equivalent for the season. Assuming a 10:1 snow ratio, that's 140 inches of snow, close to December's record total.

This deficit is important because much of the state's water supply comes from the Northern Sierra index.

Prior to this year, there were a whopping 23 La Niña patterns on record. That's a very small sample size to make blanket climatology statements. Past outcomes do not guarantee future outcomes and thus, correlating La Niña with below-average precipitation in California is not accurate.

Still, this season's dryness blew climatological records out of the water. Rain deficits going into the summer season raise major wildfire concerns, as fuels will dry out quicker in the summer, leading to high fire danger. Water resource managers will face challenges in allocating the existing water supply, leading to potential restrictions.

La Niña driven or not, the dry winter will have far-reaching impacts for many months to come.