Offshore winds in Southern California are winds that move from the interior land towards the coast (from east to west).

These winds can develop as a result of the uneven daily warming over land and water. As the sun’s rays shine down, they heat up land more than the ocean during the day, leading to onshore winds called the sea breeze; the opposite occurs at night as land loses more heat than the ocean, leading to offshore winds called the land breeze.

Land breezes can certainly fan the flames of fires already burning—for instance, the recent Bobcat Fire.

Santa Ana winds are a specific type of offshore wind, and it turns out there is more than one accepted definition of Santa Ana winds.

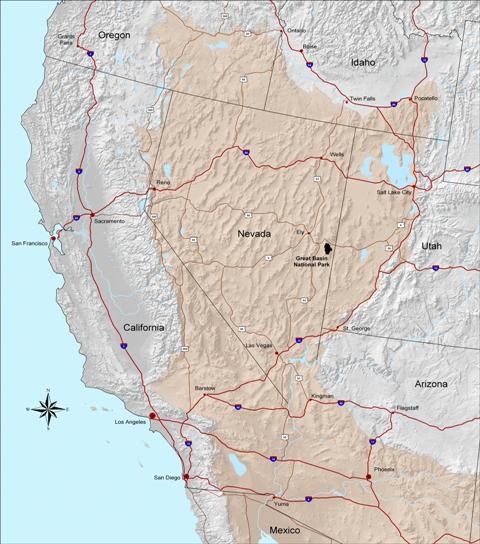

The American Meteorological Society says Santa Ana winds are driven by strong pressure gradients that develop from surface high pressure over the Great Basin.

From a wildfire perspective, another widely accepted interpretation of Santa Ana winds states that they occur in any synoptically driven (wider pattern) offshore wind event that results in warming and subsequent drying in the western side of the Southern California mountain ranges.

Santa Ana winds don't cause wildfires, but they can exacerbate a fire in a number of ways:

- Nearly eliminates moisture in the air near the ground — moisture raises ignition temperature, preventing faster spread

- Prevents overnight temperature and relative humidity recovery — a time firefighters typically use to get a better handle on fires

- Gusty winds spread flames easily, making it difficult to control especially if the two above conditions are met

Pressure imbalances drive wind in the atmosphere as air tries to reach an equilibrium and stabilize, which will never fully happen. Air moves from high to low pressure while trying to stabilize and the stronger the pressure difference, the stronger the wind. We call this difference in pressure a pressure gradient.

Pressure gradients are analyzed on weather maps by examining the “packing” of isobars — lines of constant pressure. The tighter the packing of isobars, the stronger the pressure gradient. Pressure gradients can also be analyzed numerically.

Where this tight packing of isobars occurs, or where the numerical pressure gradient number is highest, we know we can expect strong winds. This is how forecasters know where strong winds will occur.

Below is a surface analysis just this week of surface high pressure on the outskirts of the Great Basin and a tight pressure gradient over the Great Basin — a borderline Santa Ana pattern, but a good example of what forecasters look for.

Santa Ana winds examined irrespective of surface temperatures and fuel moisture are somewhat meaningless — it’s the impact of Santa Ana winds that are of particular interest, therefore the fire potential exacerbated by Santa Ana winds.

Fire scientist Tom Rolinski was one of the chief engineers of the Santa Ana Wildfire Threat Index (SAWTI), which aims to address not just the magnitude of Santa Ana winds, but the impact these winds can have on the populations of Southern California beyond windy and dry weather.

SAWTI uses two terms to calculate risk: large-fire potential and fuel moisture content. Santa Ana winds are encompassed in the large-fire potential term, along with historical fire data. Fuel moisture content analyzes dead brush, live fuels, and the green-up of annual grasses to determine what role brush on the ground could play in a developing fire.

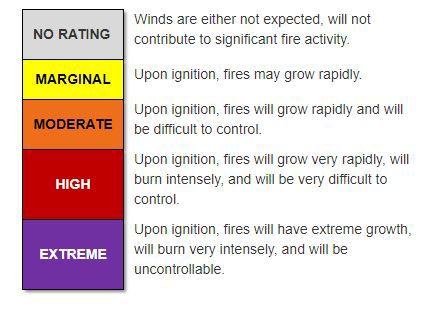

SAWTI is divided into four zones: LA-Ventura, Orange-Inland Empire, San Diego, and Santa Barbara. Ratings range from no rating to extreme.

Note: a “no rating” does not necessarily mean there will not be Santa Ana winds, it means Santa Ana winds are either not expected or will not contribute to significant fire activity.

It’s important to know not just when Santa Ana winds will occur, but when they are likely to worsen fire weather or cause any fire to spread rapidly and possibly out of control. SAWTI does an excellent job of predicting when Santa Ana winds could contribute to large fire spread. Fire agencies use this information to plan accordingly and allocate resources.

SAWTI is not designed to capture fire risk for terrain and fuel-driven wildfires, which typically occur in the summer, or for land breeze offshore winds, which aren’t technically Santa Ana winds.

SAWTI forecasts are publicly available and go out six days. You can keep up with SAWTI ratings anytime — just make sure to select the zone you are interested in when visiting their website.

So, does it matter if the offshore wind is a land breeze or Santa Ana wind? If a fire is already burning, no — any wind will make it difficult to fight an established fire.

In terms of predicting how difficult a fire would be to control given offshore wind in the forecast, land breezes are slightly easier to predict and tend not to be as strong as Santa Ana events, even weaker ones.

Of course, there are always exceptions but considering some of California's most devastating wildfires have occurred during periods of Santa Ana winds, they are certainly a little more alarming during periods of critical fire weather.