It's not uncommon to get a hurricane in the Pacific. But could hurricanes impact us here in Southern California?

We’ll walk you through hurricane dynamics, talk a little history, and explain why a (weak) hurricane is not totally out of the realm of possibility for Southern California in the future.

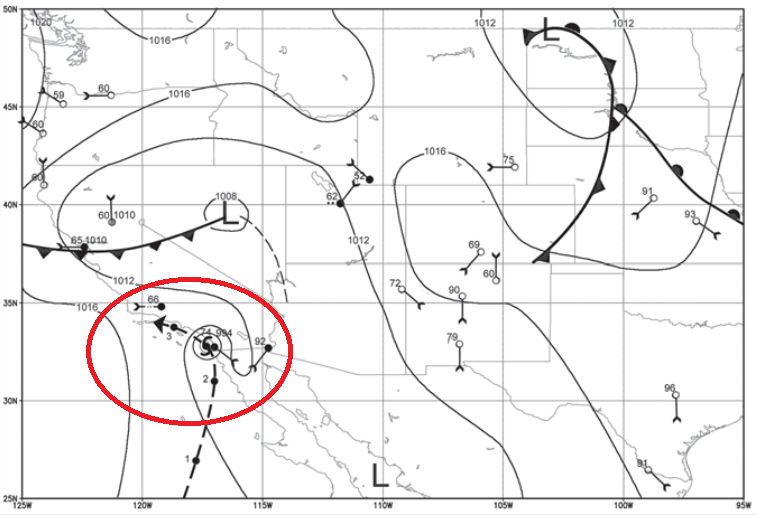

Southern California has only been hit with an intact hurricane once in recorded history. That hurricane approached San Diego on October 2, 1858, as a Category 1 storm with 80-mph winds.

The likely track of the hurricane is pieced together from U.S. Army weather observers’ data as nearing San Diego, then riding the coastline toward the Channel Islands.

The only known tropical storm to make a direct hit on Southern California was the 1939 Long Beach Storm, which killed 45 people on land.

Not only did this storm pack near hurricane-force wind, it also brought torrential rain: 4.83” in Pasadena, 5.66” in Los Angeles, and 9.02” at Mt. Wilson in a single day.

The Long Beach Storm was so devastating, it prompted the opening of a Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service) office in Southern California in 1940.

Hurricanes need warm ocean waters and warm, humid air to form and thrive.

It starts out as a typical, single thunderstorm cell forming over warm ocean waters. Then maybe another storm pops nearby.

Eventually, several cells in the same vicinity form a cluster, and the motion surrounding these storms start to form a circulation.

This cluster of storms can become a tropical cyclone and then a hurricane under the right conditions—for instance, hurricanes cannot form within 300 miles of the equator because there is no Coriolis effect at the equator.

Warm ocean waters provide the fuel to keep hurricanes going. Generally, hurricanes need a sea-surface temperature of at least 80 degrees Fahrenheit to sustain their strength.

The majority of hurricanes form and thrive in even warmer waters, greater than 82 degrees Fahrenheit.

When hurricanes encounter land or ocean waters cooler than 80 degrees, they will weaken and eventually dissipate.

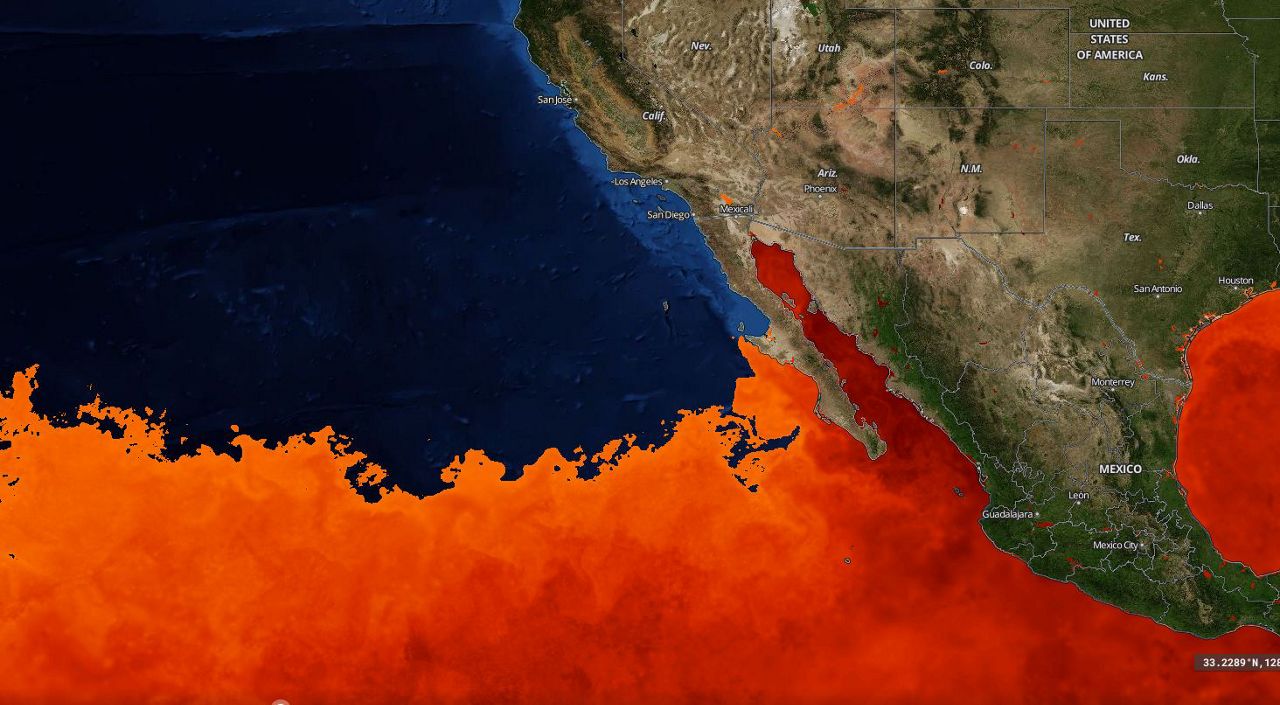

Let’s take a look at where sea-surface temperatures are greater than 80 degrees Fahrenheit in the Eastern Pacific to further illustrate where hurricanes can form.

Remember, hurricanes cannot form within 300 miles of the equator, so that eliminates some of the areas where hurricanes can thrive.

There is certainly more real estate in the Atlantic for hurricanes to thrive, with a larger swath of water above 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

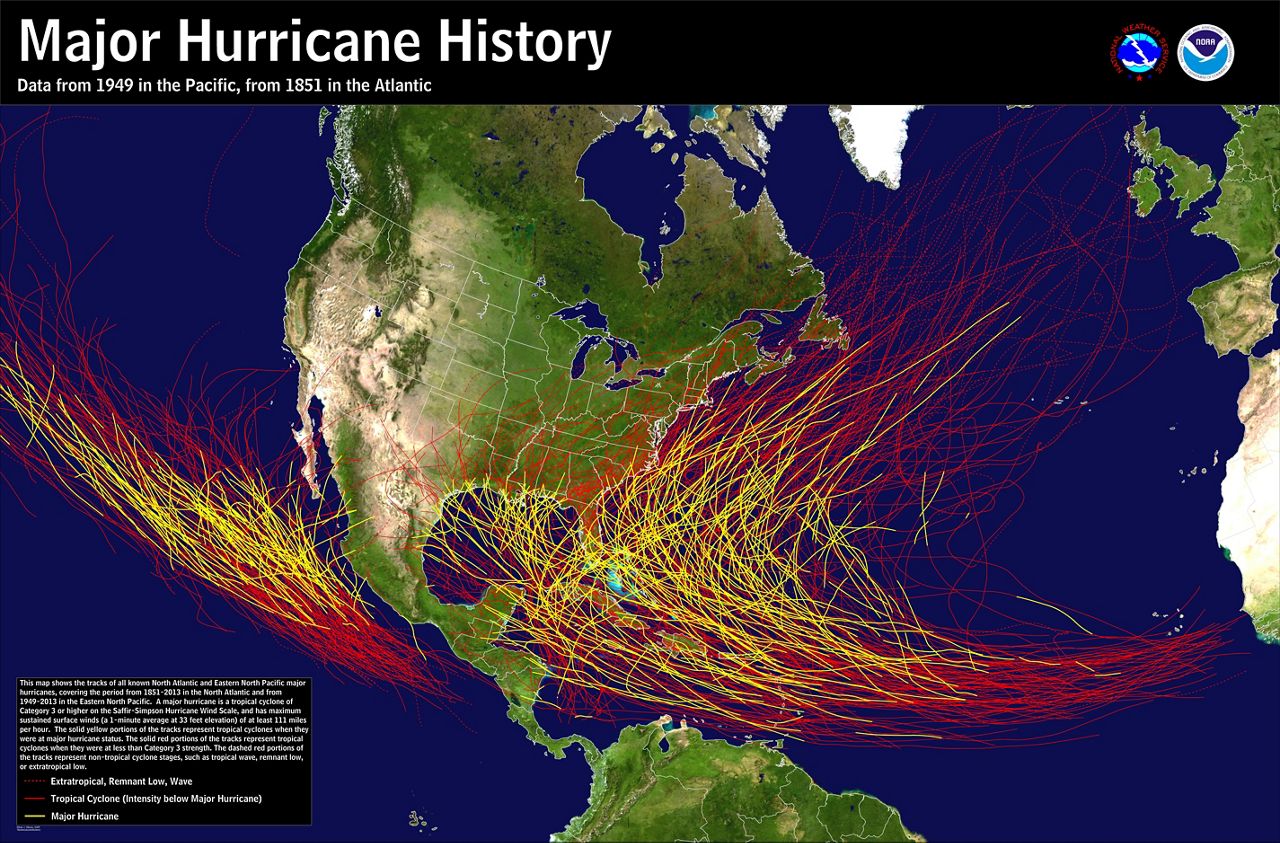

Trade winds typically carry hurricanes in a westerly direction, steering Atlantic storms directly towards the United States while Pacific storms most often go out to sea.

Storms can get caught up in the jet stream though, steering them back to the north and east. It’s in this scenario that an Eastern Pacific storm could turn towards the West Coast, potentially taking aim at California.

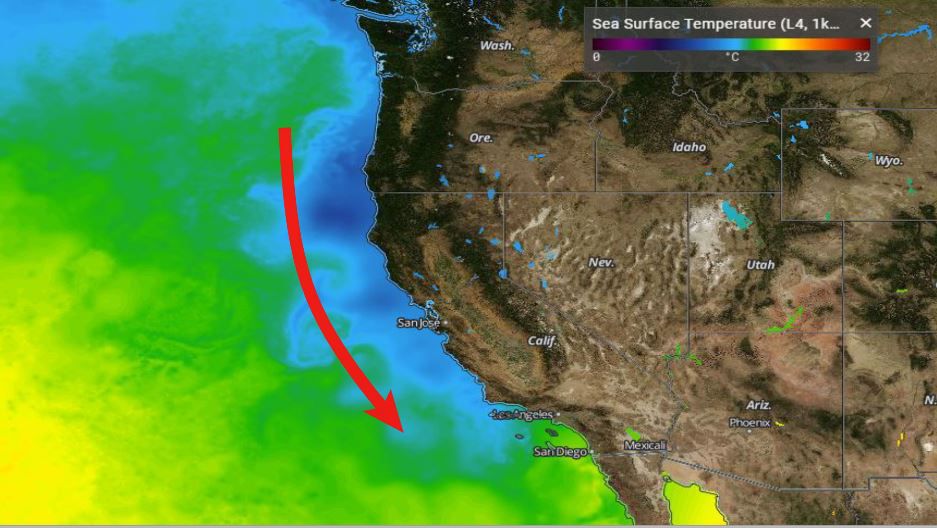

Water temperatures are simply just too cold near California to sustain a hurricane.

One of the reasons it’s so cool off the California coastline has to do with ocean currents—the California Current in particular.

The California Current displaces water at the surface along the West Coast. Water has to come from somewhere to fill the void, so it comes from below the surface, where water is cooler—a process called upwelling.

The cooler waters along the California Current are clearly visible in recent NASA imagery, represented by the blue colors adjacent to the coastline.

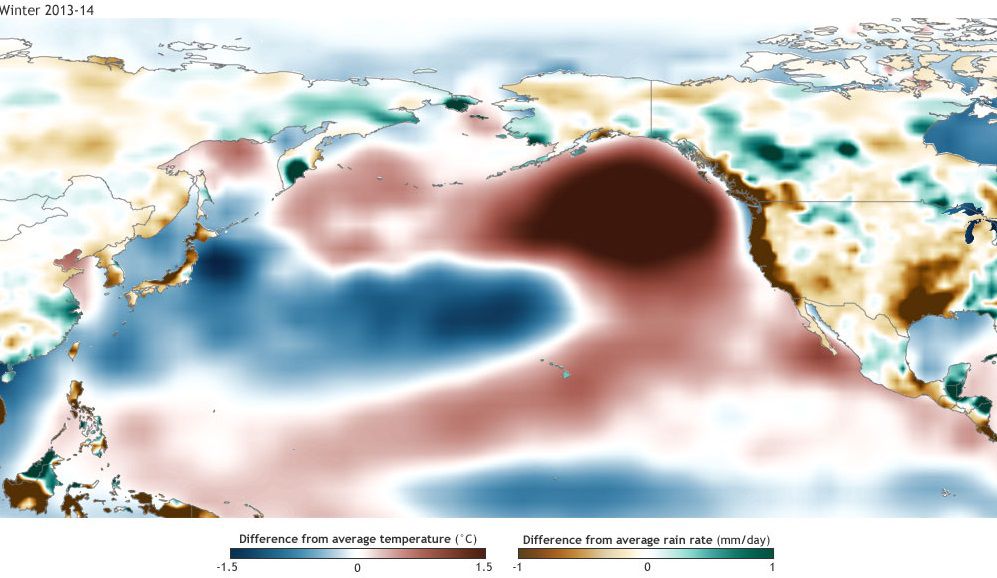

With an area of high pressure almost parked over the North Pacific in recent years, the California Current has weakened and ocean waters have been substantially warmer.

You may have heard this phenomenon referred to as “the Blob.”

But even with this warmer water farther north, there is still a huge gap in warmer waters in between the equatorial Pacific and the Blob.

The colder ocean waters just north of the tip of Baja California are where Pacific hurricanes go to die, with the Blob having no bearing on hurricane formation or sustenance.

El Niño has become part of the vernacular in Southern California—a term that has mistakingly become interchangeable with rain.

El Niño occurs when there are warmer than average sea-surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific.

The problem is El Niño regions are outside of the area where Eastern Pacific storms form, so it really has no bearing on hurricane formation.

But notably, the hurricane of 1858 and the Long Beach Storm both occurred during El Niño years.

Ocean waters are continually getting warmer farther north, meaning hurricanes can sustain themselves farther north along the Baja coastline.

Local ocean waters are also getting warmer. Scripps Pier in San Diego has set sea-surface temperature records in August the past three years, getting as high as 79.6 degrees Fahrenheit!

This means the gap of cooler waters between the equatorial Pacific and the Southern California coastline is shrinking at times.

Even if storms don’t reach Southern California as hurricanes or even as tropical storms, the remnants can pack a bigger punch if they have more time to survive as hurricanes.

If the stars align in terms of conditions—a Cat 4 or 5 storm moving very quickly over unusually warm water farther north—it’s not totally out of the realm of possibility Southern California could be hit with another strong tropical storm, or even a weak Cat 1 hurricane.

The odds remain low for an actual hurricane, but even a strong tropical storm can cause a lot of damage.