LOS ANGELES — As electric vehicles become more commonplace, so does the need for first responders to understand how to handle them in emergency situations. Whether it’s a crash or a rollover, fire or hit and run, a high-voltage EV system is still an anomaly for many fire and police officers responding to life-or-death situations where time is of the essence.

“It’s an emerging threat,” Torrance Police Department Assistant Chief Blayne Baker told Spectrum News 1.

Baker is part of a regional training group of 29 LA area fire chiefs who are developing best response practices for incidents involving the lithium ion batteries that propel everything from e-bikes to zero-emission pickup trucks.

“We want our firefighters to be comfortable when they’re approaching these types of incidents so they can be aggressive but also safe,” said Baker, who was attending a battery electric vehicle first responder training offered by General Motors Wednesday with three dozen officers from SoCal police and fire departments. “If there’s these unknowns, there’s a tendency to take a step back or to maybe slow down, so the more information we can get to our first responders, the more educated they are, the more comfortable they’re going to feel around these emergencies, the better our outcomes are going to be in the field.”

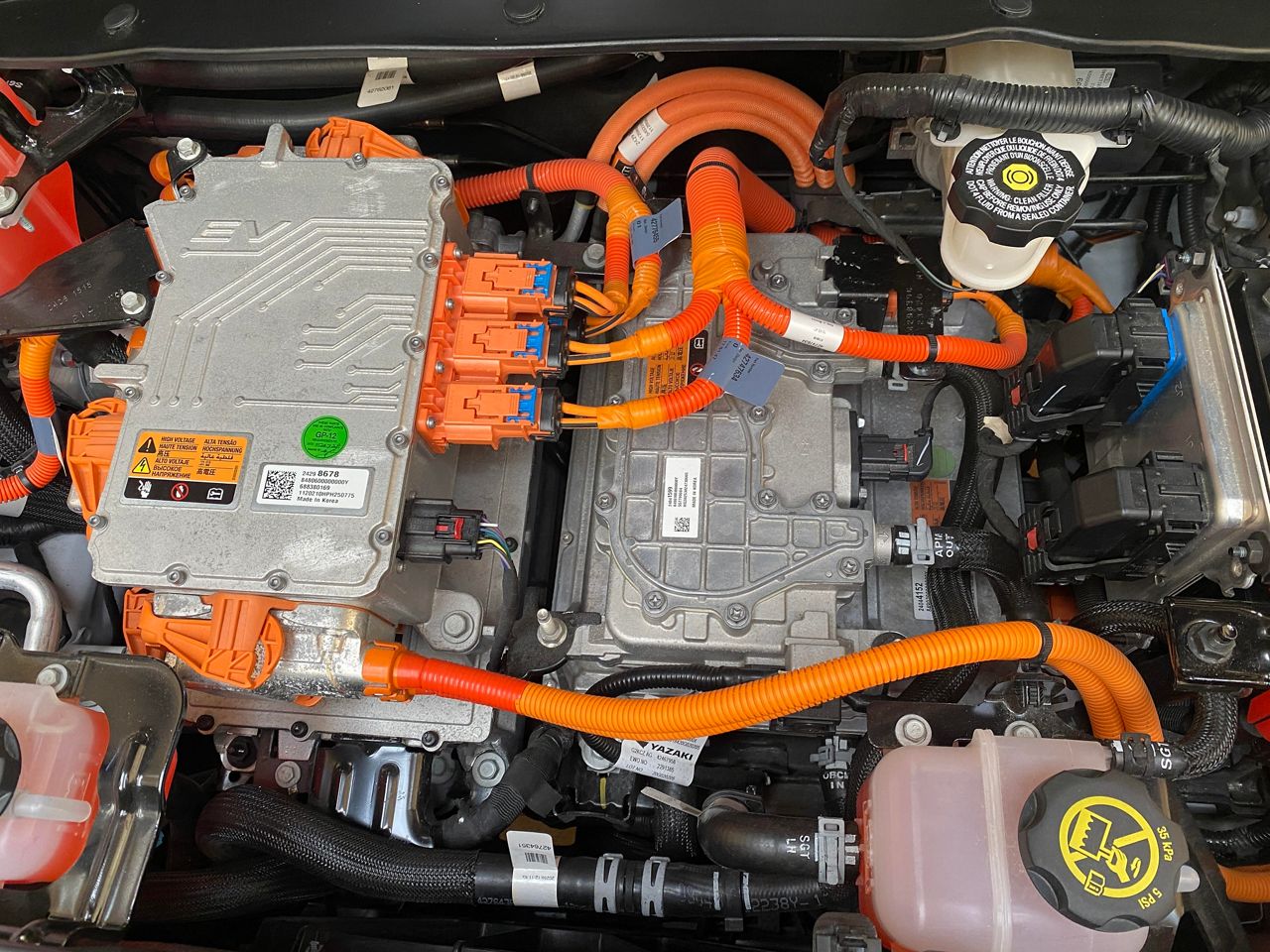

While many electric vehicle components are the same as cars powered with gas, they also contain high-voltage battery packs and companion systems that could require a different approach in an emergency.

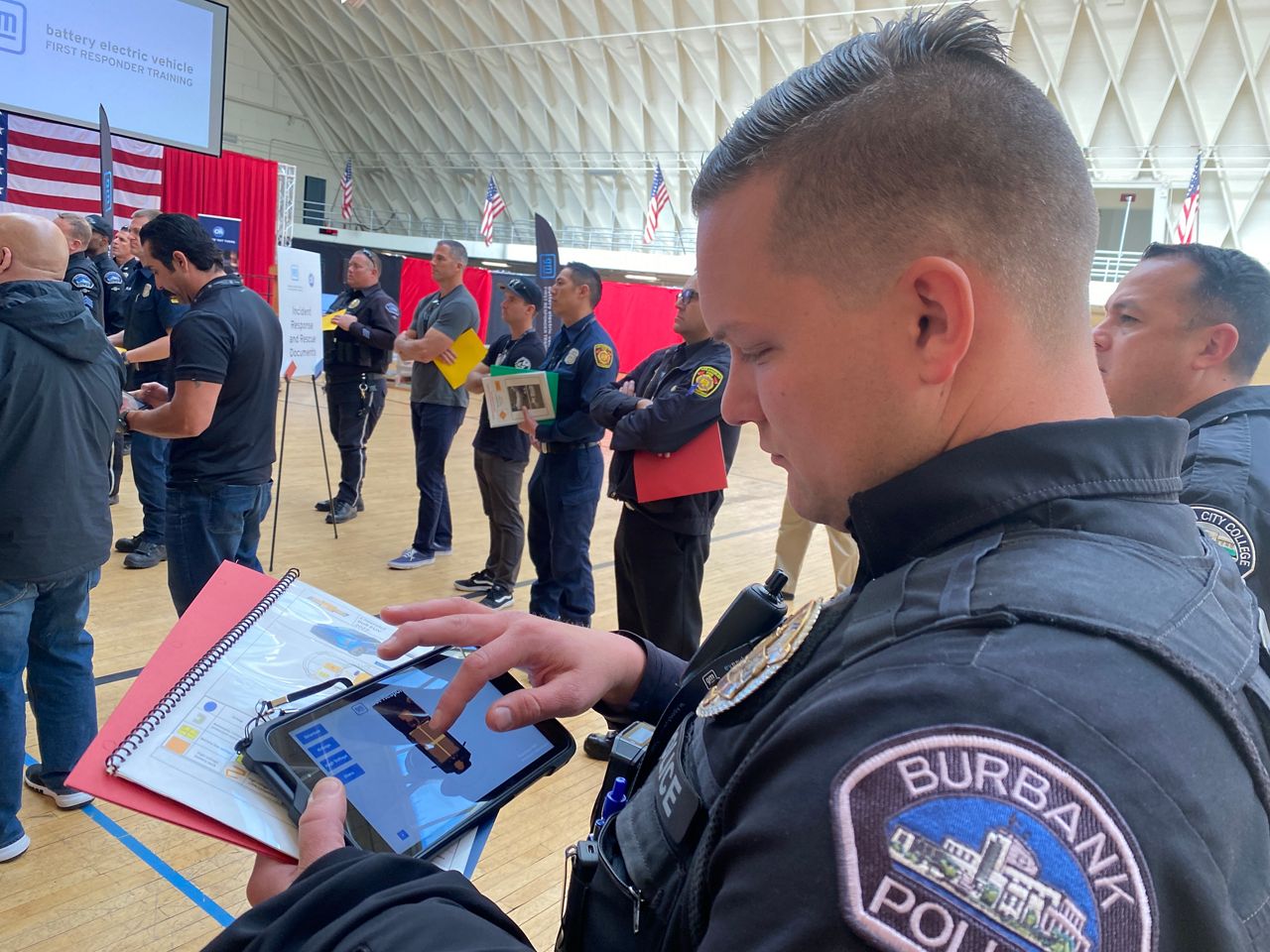

General Motors first started its battery electric vehicle first responder training tour last June and will visit almost 25 cities nationwide through this summer. On Wednesday, it stopped at the Los Angeles Fire Department Frank Hotchkin Memorial Training Center in Elysian Park, where first responders from Burbank, LA, Pasadena, Downey and Torrance spent four hours learning everything from incident response rescue documents and battery electric vehicle basics to battery pack fire suppression.

“There’s a lack of solid factual information from auto makers as well as the responder community. They want the best information they can get, and we’re here to provide that for them,” said Joseph McLaine, an automated driving systems staff engineer with General Motors who is leading the program. “The goal is to have several thousand receive the training in person face-to-face with subject matter experts.”

GM partnered with the Illinois Fire Service Institute for its curriculum. It also hauled two props to the training site: a crashed Hummer EV and the Chevrolet Bolt EUV that launched a $1 billion recall when General Motors found manufacturing defects in battery cells that caused fires in certain models.

In California, almost 19% of new passenger vehicle sales are electric, according to the California Energy Commission. While they account for just 6% of all passenger vehicles on California roads, that percentage will only increase over time as the state works to achieve Gov. Newsom’s goal of 100% electric passenger vehicle sales by 2035.

The country’s largest automaker, General Motors plans to phase out gas- and diesel-powered vehicles on the same timeline.

“We’re not stopping at EVs,” McLaine said.

GM, which sold 2.27 million vehicles in the U.S. last year and also makes several EV models, plans to integrate zero-emissions technology into watercraft, aircraft and self-driving autonomous vehicles.

As much as GM’s battery electric vehicle training is to help first responders get familiar with a technology that is expected to eventually displace gas-powered cars and trucks, it’s also a way for the automaker to solicit feedback from first responders about what they think would be helpful.

During training, GM was circulating a tablet with an app it is currently beta testing. The app could eventually be incorporated into software that is already used by first responders to prepare them for the situation they are about to encounter while they are en route.

The app provides detailed schematics about electric vehicles, including how to access them in situations where the doors might not be accessible to prevent them from cutting through high-voltage equipment or unintentionally disabling other safety features.

For Assistant Chief Baker, whose goal is to have all the 29 departments in his regional training group learn and deploy similar tactics and strategies, “it’s difficult finding subject matter experts in this field,” he said. “If I wanted to find a subject matter expert on how to fight a gymnasium fire, there’s plenty of firefighters that have done that before. Lithium ion isn’t necessarily a new technology, but firefighters themselves are not subject matter experts yet, so we’re relying on private partners like GM.”

Baker said his team is currently developing an electric battery response training module they hope to push out to 9,000 firefighters in the region by June.