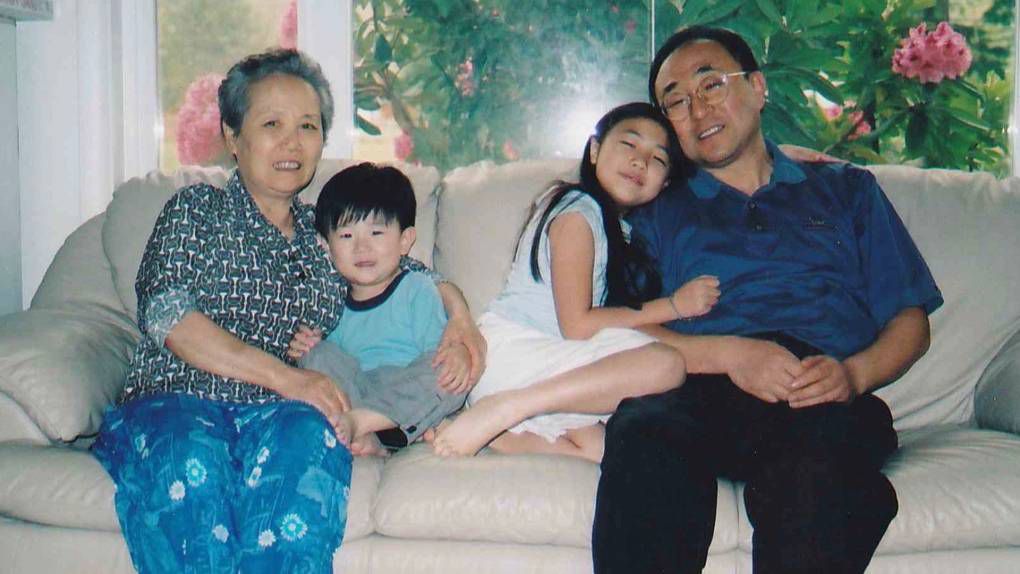

LOS ANGELES — When Hannah Kim returned home to her family’s Koreatown apartment for winter break in December 2020, she was welcomed home by her mother Eun-Ju, her father Timothy and her little brother, Joseph.

As the initial COVID wave spread throughout California, the Kims brought Eun-Ju’s mother, Soon Sun, into their already packed two-bedroom apartment.

The virus soon ravaged their home, and by the end of April, the Kim siblings found themselves alone in the once-crowded apartment, with their parents and grandmother hospitalized due to COVID. One by one, Hannah, then-22, and Joseph, then-17, watched their family slip away.

By July, the Kim siblings were orphans.

The deaths of their caregivers left Hannah and her brother with about $500 in cash, credit card debt, and no idea how they were going to support themselves financially.

In June, California became the first state to commit to long-term care of children, like the Kims, who lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19.

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a $308 billion state budget that allocates $100 million to create interest-bearing trust fund accounts for some children who lost a parent or primary caregiver to COVID-19 and long-term foster youth.

The details of the plan will be laid out in a trailer bill later this summer, but Shimica Gaskins, president and CEO of GRACE and End Child Poverty California, said the hope is that the initial deposits will be somewhere between $1,000 to $3,000. The growth of accounts, known as "baby bonds," will depend on the child’s age at the time of eligibility.

The HOPE trust accounts, Gaskins said, aim to provide financial stability for these vulnerable groups and help close the racial wealth gap.

“This is a start,” Gaskins said. “We are looking forward to growing the program to include all low-income children. We’re just excited that we have sufficient funding to get the program launched and that we’ll reach several thousand children with this initial program.”

In California, 32,219 children lost a primary or secondary caregiver to COVID-19, according to the Global Reference Group for Children Affected by COVID-19.

Emily Walton, policy director of COVID Survivors for Change, emphasized that the funding, which she called “a quite modest amount of money,” in no way makes up for the death of a family member or a caregiver.

“It’s just something to help them not fall through the cracks, as it were,” she explained. “It’s just something to build a small, modest bridge so that they can move on to the next phase of their life."

While other states have introduced baby bond bills, California is the first to create trust fund accounts specifically for long-term foster youth and COVID-bereaved children.

Although Hannah will not be eligible for the program, she said having a program-funded savings account would have been “a beacon of light” during the dark times of her financial uncertainty. The Kim siblings relied on the help of their community, largely donations from a GoFundMe page, to get by. Without that support, Hannah says she would have had to work multiple jobs or would have been at risk of being homeless.

“I didn’t have extra cash on me. My parents, you know, they were immigrants. They were always scrapping for money and never had a lot of money. And so, it wasn’t like I could lean on savings. They didn’t have any.”

Advocates hope that the program will inspire other state legislatures to adopt similar methods of care, with an ultimate goal of universality.

“If we can do it here in California, they can surely do it at the federal level,” Gaskins said.

The COVID policy response to date has largely focused on the immediate emergency — containing the spread, preventing deaths and the boosting economy. This, Walton says, presents a problem for the children who have been left without a parent, caregiver or advocate.

Roughly $5 trillion in pandemic stimulus has been spent to bolster the U.S. economy since the onset of the pandemic — the greatest government relief effort in history. Yet, none of that funding has gone to caring for those experiencing the secondary effects of the pandemic, namely, the children left behind.

In the U.S., about 263,900 children have lost a primary or secondary caregiver to COVID, according to Imperial College London Global Reference Group.

Catherine Jaynes, a senior director of the COVID Collaborative in charge of the Hidden Pain initiative, which focuses on children who have lost a parent or caregiver to COVID, says the U.S. has the resources to support these children.

“There’s a significant amount of money that hasn’t been drawn down from the Recovery Act,” Jaynes said, adding that the COVID Collaborative hopes it can encourage members of Congress to allocate funding for bereavement and create greater flexibility within existing programs to include children who have lost a caregiver.

“I think it’s in our blood to support those children that have been involved in tragedy,” she said. “We saw it after 9/11. We saw it after Katrina. And so we’re hoping that the public doesn’t get weary and move on, and move past so many of these children that, as we know, are still suffering.”