A recent study out of the United Kingdom found those who are vaccinated against the human papillomavirus (HPV) face a “substantial reduction” in developing cervical cancer later on in life.

The study, published Wednesday in the medical journal The Lancet, was funded by Cancer Research U.K. and conducted by researchers from King’s College London. It observed the impact of the Cervarix vaccine, which in 2008 was introduced as a routine vaccination program for women in the U.K. to protect against cervical cancer and non-invasive cervical carcinomas.

Scientists observed three separate age groups of British women who received the vaccine — those between 12-13 years old, 14-16 years old and 16-18 years old — compared to the same age groups who were not vaccinated against the virus to assess the “estimated relative reduction in cervical cancer rates by age at vaccine offer,” experts wrote in part.

Data showed that the vaccine was most effective at preventing cervical cancer for those in the 12-13 age group, with a relative reduction rate of 87%. Those who were vaccinated between 14-16 years old had a 62% reduction rate in cervical cancers, while those vaccinated between 16-18 years old had a 34% reduction rate.

The study also examined reduction rates of CIN3, an abnormality of the cervical tissue that poses a “high chance” of becoming cancerous, between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts.

Reduction of the CIN3 abnormalities were even more drastic than cervical cancer across all age groups, according to the data. Women vaccinated between 12-13 years old had a 97% reduction rate of CIN3, compared to a 75% and 39% reduction rate for women vaccinated between the ages of 14-16 and 16-18, respectively.

“This represents an important step forwards in cervical cancer prevention,” Dr. Kate Soldan, co-author of the study, wrote in a statement. “We hope that these new results encourage uptake as the success of the vaccination programme relies not only on the efficacy of the vaccine but also the proportion of the population vaccinated.”

HPV is a sexually transmitted infection and, while most cases typically disappear and do not cause long-term health issues, can occasionally cause genital warts or cancer. The types of HPV that cause cancers are not the same as those that cause genital warts, both of which can take years or decades to develop after an individual first contracted HPV.

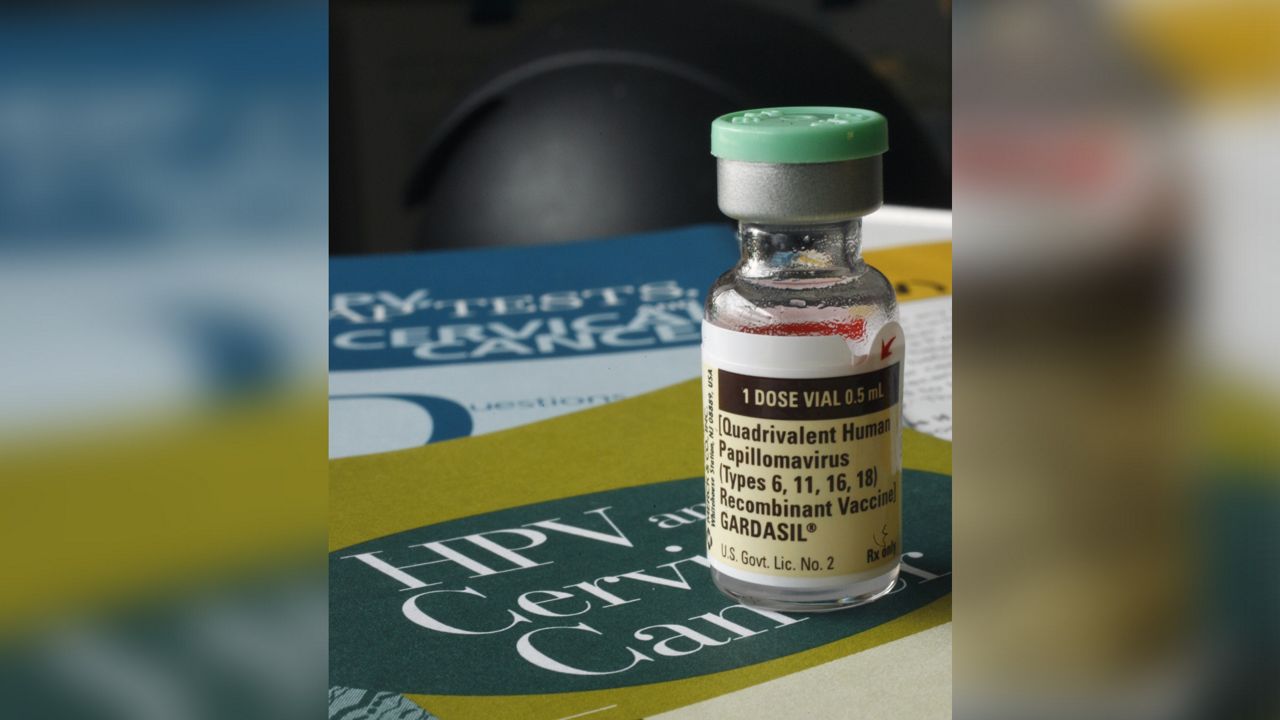

There are many strains of HPV, which is the most prevalent sexually transmitted disease in the United States. Merck’s Gardasil-9 vaccine is the only HPV vaccine currently distributed in the United States; the United Kingdom used Cervarix from 2008-2012, when it switched to Gardasil’s quadrivalent vaccine.

Cervarix is a bivalent vaccine, meaning it protects against two strains of HPV — namely, strains 16 and 18, which cause an estimated 70% of cervical cancers and pre-cancerous abnormalities around the globe, according to the World Health Organization.

Gardasvil’s quadrivalent vaccine protects against strains 16 and 18, as well as 6 and 11, the most common strains that cause anogenital warts. Gardasil-9 protects against the same strains, plus HPV 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58, which cause an estimated 15% of cervical cancers.