LOS ANGELES — Los Angeles County is considering how best to relieve low-income renters of pandemic-induced rental debt, which one tenants-rights advocate called “unprecedented and bold.”

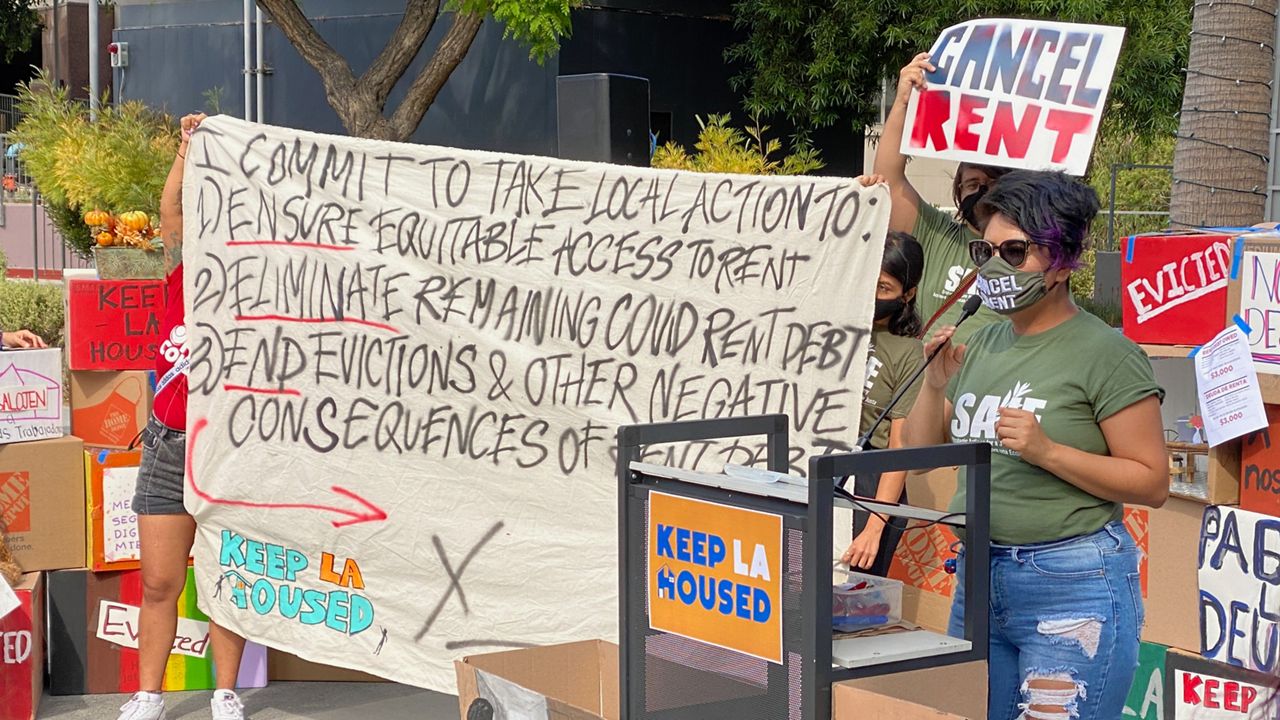

Such advocates, such as the Keep LA Housed coalition, believe LA County could take a range of actions — including something akin to eminent domain, but for debt — to protect tenants and prevent homelessness.

At the county Board of Supervisors’ June 8 meeting, Board Chair and First District Supervisor Hilda Solis was unanimously supported in a motion directing staff for an exhaustive report examining the extent of rental debt within Los Angeles County, legal avenues the county might use to eliminate COVID-related rental debt, and potential viable sources. The motion, and any subsequent potential action, is intended to prevent a surge of homelessness once COVID-era tenant protections expire.

“That’s why I brought this motion forward, because we urgently need to come up with an out-of-the-box strategy that comes up with solutions to stretch the federal rental assistance funding as far as possible, and helps us resolve the rent debt,” Solis said, adding that statewide rental-relief programs have left “many tenants behind by making the programs too narrow and scope and difficult to access.”

The report also asks staff to determine the “estimated average fair market value of residential COVID-19 rental debt owed by a low-income tenant whose landlord has refused to accept rental assistance” — as well as estimates of collective rental debt across the county, estimated need for rental assistance, and estimates of landlords across the county. A report is due to come back before the Board of Supervisors as early as mid-July.

Requesting a value estimate for such a limited-sounding portion of residents may seem restrictive, but Solis’ motion cites HUD data estimating that more than one million LA County tenant households qualified as low-income before the pandemic. Her motion also quotes a calculation that county renters may owe nearly $1 billion in back rent.

The actions being investigated by the county would go a long way toward helping residents like Irma Cervantes, a single mother raising five kids in a one-room, converted garage. Pre-pandemic, her ex-husband would work to support their children. But after COVID hit, two problems happened — first, his work as a street vendor dried up; second, he has been sick and unable to work.

Cervantes’ landlord, as she explained in Spanish through a translator, has continually asks her for back rent, pushing Cervantes to move out so the landlord can find a tenant who can pay. The stress has been overwhelming, she said.

Cervantes, therefore, has been working with the Keep LA Housed coalition, a group of community organizations that includes Inner City Struggle, Strategic Actions for a Just Economy, Community Coalition South LA, among many other tenants-rights groups. On June 1, Keep LA Housed announced a list of demands for elected officials to follow in order to protect tenants — including forgiveness of rental debt.

Ruby Rivera, the Director of Community Organizing with Inner City Struggle, said that Solis’ motion isn’t the perfect solution, but it is a solution.

“For us, debt seizure is important, because if we feel if the county is able to take on that debt, and take it off the backs of the tenants, the county can make the funds that come later down the line last, and make them go further,” Rivera said. “That’s why this motion can be restrictive. What the study is focusing on is the big pieces. We want there to be a stud to show that it can happen... Once they get the report back in 45 days, we can use the findings for advocate for a policy that affects real change… I think it’s unprecedented and bold. But it has been found to be legally sound.”

Greg Bonett, an attorney with pro bono public interest law firm Public Counsel, which is also working with the coalition, said that there are a few legal levers that LA County could attempt.

“The most familiar example that demonstrates that governments have the power to take ownership of property, in exchange for fair compensation where the owner doesn’t want to sell, is eminent domain,” Bonett said. “That power isn’t limited to real estate. It could be applied to non-tangible property.”

The key, Bonett said, is for the county to set up a framework where landlords are required to relinquish their debt in exchange for payment — hence the sections of Solis’ motion seeking various rental data estimates.

At the June 8 meeting, Third District Supervisor Sheila Kuehl admitted that she’s not yet certain if she’s willing to acquire rental debt, she believes the report will prove valuable.

“This motion directs the departments to get truly essential information about the amount of debt and prospective rent still owed which, in addition to looking at whether whether public funds should be utilized to pay off that debt, also will give us a lot of good information to guide our future tenant protection policies and programs,” Kuehl said.