LOS ANGELES — It was late February 2009, and Ryan Ballard couldn’t believe what he was seeing in the Los Angeles Times, and neither could his father.

“I’m at work, I call him, and he’s looking at the paper too — and he cut me off,” Ballard said. “The first thing my dad said to me was, ‘Hey Ryan, I’m looking at the paper, and this fella reminds me of my grandfather.”

That fellow was John Ballard, the namesake of Ballard Mountain and the first Black person to settle in the hills north of Malibu.

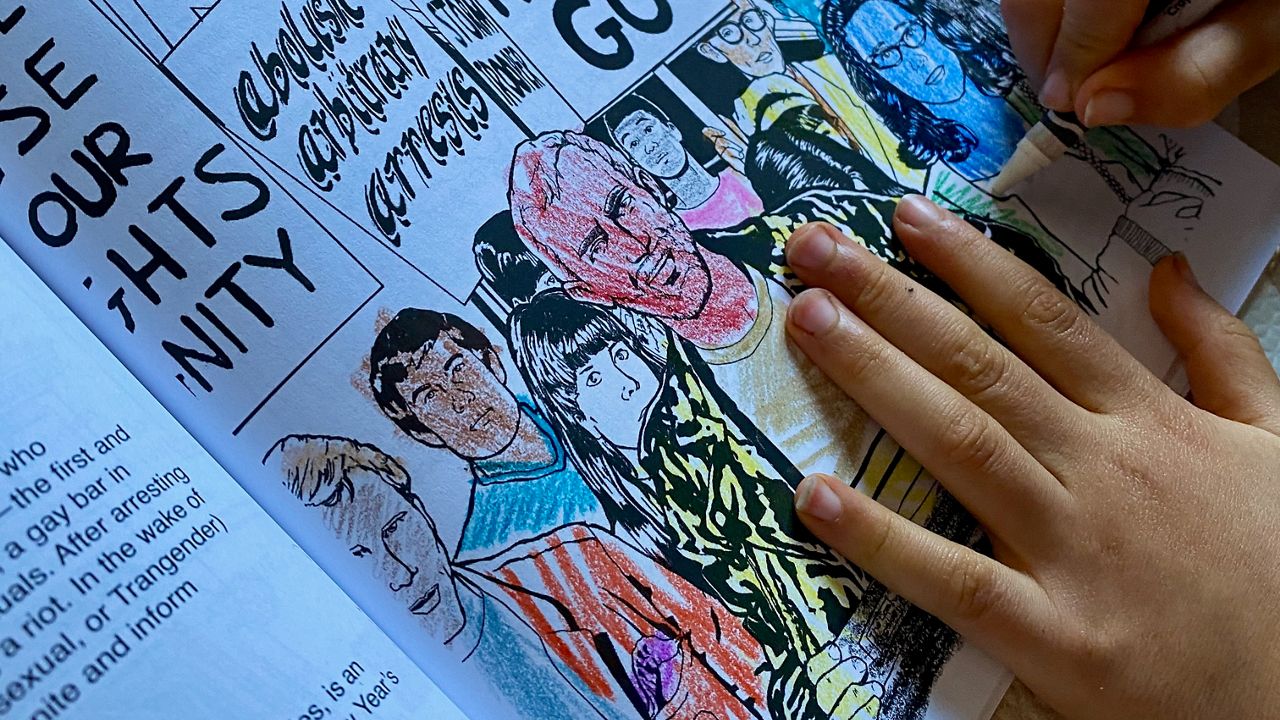

On Friday, the Los Angeles Public Library honored Ballard among more than a dozen other lesser-known trailblazers of the Southland with the launch of the “Hidden Heroes, Historic Places” coloring book. The book, which is priced at $10.99, is available at LAPL's online store.

“We wanted to celebrate our community and profile people with stories of historic deeds within their own communities,” said librarian Vi Ha, who helps run LAPL’s Octavia Lab, named for sci-fi writer Octavia Butler.

The Octavia Lab is the library’s “maker space,” a home for LAPL’s 3D printers and entrepreneurs. The Octavia Lab opened in June 2019, and over the past two years, has shifted gears into creating hospital-grade face shields for the Los Angeles community.

The “Hidden Heroes” book, presented by LAPL, BEST Friends, and the Los Angeles Conservancy, is designed as a fundraiser for the lab — and the lab’s namesake makes an appearance as well, presented before the Central Library Hope Street entrance.

The book itself includes 15 black-and-white images, as well as biographies of the people included — activists like Julius Levitt and Aristide Laurent, educators like Dr. Virginia Uribe and Mildred Walizer, and entrepreneurs like Ah-Wane-U Sharon and Drs. Vada and John Somerville — chosen for their work and their lives. And on Friday, the virtual book launch included Ryan Ballard telling his family’s story.

In the mid-1800s, formerly-enslaved John and Amanda Ballard migrated across the country to Los Angeles. After living and working in the city, the Ballards were priced out and resettled in the hills above Malibu.

For their trouble, the area upon which they settled was eventually called “Negrohead Mountain” — its original name contained an anti-Black slur until the 1960s. The push to rename it as “Ballard Mountain,” which revealed their family ties to Ryan Ballard and his family, came in late 2009.

To that point, Ryan had no idea his family was related to a pioneering settler — he just knew that Ballard's roots ran deep in Los Angeles.

When the coloring book came to pass, Ha said that the goal was to connect with people who were a part of the history and legacy of the heroes they were profiling.

“When you think of heroes, the book is very flattering. But one think I know about heroes is is that they don’t seek celebrity. They just do what they need to do, and I think that’s the case of John Ballard,” Ryan Ballard said on Friday.

“That’s why I’m excited to be among this group of individuals somebody thought it worth to tell the story.”

In an interview with Spectrum News, Ballard said that he believes the changes that the racial reckoning that the country has undergone in recent years can be continued and strengthened through education. He gestured toward the concept of February as Black History Month and why it is celebrated.

“It’s because it was intentionally left out, so we’ve got to be just as intentional to promote it,” Ballard said.

Lorena Villegas spoke on Friday as well, representing her husband, Aurelio Jose Barrera. Barrera was a longtime photographer for the LA Times, a Pulitzer Prize winner, and in his later years, an advocate who took it upon himself to distribute food to unhoused people in his East L.A./Commerce-area neighbors.

“He never sought out fame or fortune or ambition. His values were with community and with grassroots,” Villegas told Spectrum News. “I think this kind of recognition is right up with what he would like: being grouped with others who, like the other speaker said, didn’t seek out to be heroes.”

Villegas met Barrera in 2003, and their courtship was like a bolt of lightning — they married quickly and remained together until his death in October last year. She didn’t learn he had won one of the greatest prizes in journalism until years into their marriage.

But that was fitting, she said — Barrera was a man who was driven to keep doing. After a heart attack in 2013, he began riding a bicycle to improve his cardiovascular health. On his rides, he observed the growth in homelessness, and with the support of friends and neighbors, began to collect unused backyard fruit and deliver it to unhoused neighbors.

“I think the library is the perfect place to have a project like this...these people, they’re not famous. Los Angeles has a lot of fame,” Villegas said. “But there’s a whole other side to L.A., and I think the library knows that and that people are hungry for that… it’s a noble thing, just like the people that are featured are noble people who just did something good because they felt like it had to be done.”